Scan barcode

glenncolerussell's reviews

1456 reviews

Letters from a Stoic: Epistulae Morales Ad Lucilium by Lucius Annaeus Seneca

These letters of Roman philosopher Seneca are a treasure chest for anybody wishing to incorporate philosophic wisdom into their day-to-day living. By way of example, below are a few Seneca gems along with my brief comments:

“Each day acquire something which will help you to face poverty, or death, and other ills as well. After running over a lot of different thoughts, pick out one to be digested throughout the day.” -------- I’m completely with Seneca on this point. I approach the study of philosophy primarily for self-transformation. There is no let-up in the various challenges life throws at us – what we can change is the level of wisdom we bring to facing our challenges.

“It is not the man who has too little who is poor, but the one who hankers after more.” ---------- This is the perennial philosophy from Aristotle to Epicurus to Epictetus to Buddha: we have to face up to our predicament as humans; we are in the realm of desire. The goal of living as a philosopher is to deal with our desires in such a way that we can maintain our tranquility and joy.

“But if you are looking on anyone as a friend when you do not trust him (or her) as you trust yourself, you are making a grave mistake, and have failed to grasp sufficiently the full force of true friendship.” --------- Friendship was one key idea in the ancient world that modern philosophy seems to have forgotten. Seneca outlines how we must first test and judge people we consider as possible friends, but once we become friends with someone, then an abiding and complete trust is required.

“The very name of philosophy however modest the manner in which it is pursued, is unpopular enough as it is: imagine what the reaction would be if we started dissociating ourselves from the conventions of society. Inwardly everything should be different but our outward face should conform with the crowd. Our clothes should not be gaudy, yet they should now be dowdy either. . . . Let our aim be a way of life not diametrically opposed to, but better than that of the mob.”. ---------- The call of true philosophy isn’t an outward display but an internal attitude. There is a long, noble tradition of living the life of a philosopher going back to ancient Greece and Rome, that has, unfortunately, been mostly lost to us in the West. It is time to reclaim our true heritage.

“You may be banished to the end of the earth, and yet in whatever outlandish corner of the world you may find yourself stationed, you will find that place, whatever it may be like, a hospitable home. Where you arrive does not matter so much as what sort of person you are when you arrive there." -------- This is the ultimate Stoic worldview: our strength of character is more important that the particular life situation we find ourselves in. Very applicable in our modern world; although, chances are we will not be banished to another country, many of us will one day be banished to a nursing home.

“This rapidity of utterance recalls a person running down a slope and unable to stop where he meant to, being carried on instead a lot farther than he intended, at the mercy of his body’s momentum; it is out of control, and unbecoming to philosophy, which should be placing her words, not throwing them around.” --------- The ancient world had many people who talked a mile a minute, an unending gush of chatter. The Greco-Roman philosophers such as Seneca and Plutarch warn against garrulousness. Rather, we should mark our words well. From my own experience, when I hear long-winded pontifications, I feel like running away.

“The next thing I knew the book itself had charmed me into a deeper reading of it there and then. . . . It was so enjoyable that I found myself held and drawn on until I ended up having read it right through to the end without a break. All the time the sunshine was inviting me out, hunger prompting me to eat, the weather threatening to break, but I gulped it all down in one sitting.” --------- Ah, the experience of being pulled into a good book! When we come upon such a book, go with it!

5.0

These letters of Roman philosopher Seneca are a treasure chest for anybody wishing to incorporate philosophic wisdom into their day-to-day living. By way of example, below are a few Seneca gems along with my brief comments:

“Each day acquire something which will help you to face poverty, or death, and other ills as well. After running over a lot of different thoughts, pick out one to be digested throughout the day.” -------- I’m completely with Seneca on this point. I approach the study of philosophy primarily for self-transformation. There is no let-up in the various challenges life throws at us – what we can change is the level of wisdom we bring to facing our challenges.

“It is not the man who has too little who is poor, but the one who hankers after more.” ---------- This is the perennial philosophy from Aristotle to Epicurus to Epictetus to Buddha: we have to face up to our predicament as humans; we are in the realm of desire. The goal of living as a philosopher is to deal with our desires in such a way that we can maintain our tranquility and joy.

“But if you are looking on anyone as a friend when you do not trust him (or her) as you trust yourself, you are making a grave mistake, and have failed to grasp sufficiently the full force of true friendship.” --------- Friendship was one key idea in the ancient world that modern philosophy seems to have forgotten. Seneca outlines how we must first test and judge people we consider as possible friends, but once we become friends with someone, then an abiding and complete trust is required.

“The very name of philosophy however modest the manner in which it is pursued, is unpopular enough as it is: imagine what the reaction would be if we started dissociating ourselves from the conventions of society. Inwardly everything should be different but our outward face should conform with the crowd. Our clothes should not be gaudy, yet they should now be dowdy either. . . . Let our aim be a way of life not diametrically opposed to, but better than that of the mob.”. ---------- The call of true philosophy isn’t an outward display but an internal attitude. There is a long, noble tradition of living the life of a philosopher going back to ancient Greece and Rome, that has, unfortunately, been mostly lost to us in the West. It is time to reclaim our true heritage.

“You may be banished to the end of the earth, and yet in whatever outlandish corner of the world you may find yourself stationed, you will find that place, whatever it may be like, a hospitable home. Where you arrive does not matter so much as what sort of person you are when you arrive there." -------- This is the ultimate Stoic worldview: our strength of character is more important that the particular life situation we find ourselves in. Very applicable in our modern world; although, chances are we will not be banished to another country, many of us will one day be banished to a nursing home.

“This rapidity of utterance recalls a person running down a slope and unable to stop where he meant to, being carried on instead a lot farther than he intended, at the mercy of his body’s momentum; it is out of control, and unbecoming to philosophy, which should be placing her words, not throwing them around.” --------- The ancient world had many people who talked a mile a minute, an unending gush of chatter. The Greco-Roman philosophers such as Seneca and Plutarch warn against garrulousness. Rather, we should mark our words well. From my own experience, when I hear long-winded pontifications, I feel like running away.

“The next thing I knew the book itself had charmed me into a deeper reading of it there and then. . . . It was so enjoyable that I found myself held and drawn on until I ended up having read it right through to the end without a break. All the time the sunshine was inviting me out, hunger prompting me to eat, the weather threatening to break, but I gulped it all down in one sitting.” --------- Ah, the experience of being pulled into a good book! When we come upon such a book, go with it!

On the Aesthetic Education of Man by Friedrich Schiller

Aesthetics is the branch of philosophy addressing beauty, taste, art and the sublime. After studying what philosophers have to say on this topic, it is refreshing to read the philosophical reflections on aesthetics by Friedrich Schiller (1769-1805), a man who was not only a first-rate thinker but a great poet and playwright. And Schiller tells us he is drawing his ideas from his life rather than from books and is pleading the cause of beauty before his very own heart that perceives beauty and exercises beauty's power.

Writing at the end of the 18th century, Schiller reflects on the bitter disappointment of the aftermath of the French Revolution where an entire society degenerated into violence. What can be done? As a true romantic, he sees beauty and art coming to the rescue.

Schiller writes how idealized human nature and character development is a harmonizing and balancing of polarities - on one side we have the rational, that is, contemplative thought, intelligence and moral constraint and on the other side we have the sensual, feeling, physical reality. Lacking this balance, harmony and character, Schiller perceives widespread disaster for both lower and higher social classes, that is, people of the lower classes living crude, coarse, lawless, brutal lives and people of the higher, civilized classes are even more repugnant, living lethargic, slothful, passive lives. Not a pretty picture, to say the least.

We might think scientists or hard working business people might stand a better chance at achieving balance, harmony and character. Sorry; the news is not good here either. Schiller writes, "But the predominance of the analytical faculty must necessarily deprive the fancy of its strength and its fire, and a restricted sphere of objects must diminish its wealth. Hence the abstract thinker very often has a cold heart, since he analyzes the impressions which really affect the soul only as a whole; the man of business has very often a narrow heart, because imagination, confined within the monotonous circle of his profession, cannot expand to unfamiliar modes of representation."

So, what must be done to restore a population's needed balance, harmony and character? Again, for Schiller, beauty and art to the rescue. One key idea in making beauty and art a central component of people's lives is what he terms `the play drive'. Schiller writes: "Man plays only when he is in the full sense of the word a man, and he is only wholly man when he is playing" By play, Schiller doesn't mean frivolous games, like a mindless game of cards; rather, play for Schiller is about a spontaneous and creative interaction with the world.

To flesh out Schiller's meaning of play, let's look at a couple of examples. In the morning you consult your auto manual to fix a problem with the engine and then in the afternoon you examine a legal document to prepare to do battle in court. Since in both cases you are reading for a specific practical purpose or goal, according to Schiller, you are not at play. In the evening you read Shakespeare. You enjoy the beauty of the language and gain penetrating insights into human nature. Since your reading is not bound to any practical aim, you are free to let your imagination take flight and explore all the creative dimensions of the literary work. According to Schiller, you are "at play" and by such playing in the fields of art and beauty, you are free.

And where does such play and spontaneous creativity ultimately lead? Schiller's philosophy is not art-for-art's sake, but art for the sake of morality and freedom and truth. If Schiller could wave a magic wand, everybody in society would receive an education in beauty by way of art, literature and music. And such education would ultimately nurture a population of men and women with highly developed aesthetic and moral sensibilities who could experience the full breathe and depth of what it means to be alive. Or, to put it another way, with a restored balance, harmony and character, people would no longer be slaves to the little world of their gut or the restricted world of their head, but would open their hearts and directly experience the fullness of life. And experiencing the fullness of life, for Schiller, is true freedom.

How realistic is Schiller's educational program as a way of transforming society? Perhaps being realistic is not exactly the issue. After all, Frederick Schiller was an idealist. He desired to see a society of men and women appreciating art and beauty and having their aesthetic appreciation color everyday behavior, so much so that their dealings and activity in the world would serve as a model of noble, moral conduct for all ages. Not a bad vision.

5.0

Aesthetics is the branch of philosophy addressing beauty, taste, art and the sublime. After studying what philosophers have to say on this topic, it is refreshing to read the philosophical reflections on aesthetics by Friedrich Schiller (1769-1805), a man who was not only a first-rate thinker but a great poet and playwright. And Schiller tells us he is drawing his ideas from his life rather than from books and is pleading the cause of beauty before his very own heart that perceives beauty and exercises beauty's power.

Writing at the end of the 18th century, Schiller reflects on the bitter disappointment of the aftermath of the French Revolution where an entire society degenerated into violence. What can be done? As a true romantic, he sees beauty and art coming to the rescue.

Schiller writes how idealized human nature and character development is a harmonizing and balancing of polarities - on one side we have the rational, that is, contemplative thought, intelligence and moral constraint and on the other side we have the sensual, feeling, physical reality. Lacking this balance, harmony and character, Schiller perceives widespread disaster for both lower and higher social classes, that is, people of the lower classes living crude, coarse, lawless, brutal lives and people of the higher, civilized classes are even more repugnant, living lethargic, slothful, passive lives. Not a pretty picture, to say the least.

We might think scientists or hard working business people might stand a better chance at achieving balance, harmony and character. Sorry; the news is not good here either. Schiller writes, "But the predominance of the analytical faculty must necessarily deprive the fancy of its strength and its fire, and a restricted sphere of objects must diminish its wealth. Hence the abstract thinker very often has a cold heart, since he analyzes the impressions which really affect the soul only as a whole; the man of business has very often a narrow heart, because imagination, confined within the monotonous circle of his profession, cannot expand to unfamiliar modes of representation."

So, what must be done to restore a population's needed balance, harmony and character? Again, for Schiller, beauty and art to the rescue. One key idea in making beauty and art a central component of people's lives is what he terms `the play drive'. Schiller writes: "Man plays only when he is in the full sense of the word a man, and he is only wholly man when he is playing" By play, Schiller doesn't mean frivolous games, like a mindless game of cards; rather, play for Schiller is about a spontaneous and creative interaction with the world.

To flesh out Schiller's meaning of play, let's look at a couple of examples. In the morning you consult your auto manual to fix a problem with the engine and then in the afternoon you examine a legal document to prepare to do battle in court. Since in both cases you are reading for a specific practical purpose or goal, according to Schiller, you are not at play. In the evening you read Shakespeare. You enjoy the beauty of the language and gain penetrating insights into human nature. Since your reading is not bound to any practical aim, you are free to let your imagination take flight and explore all the creative dimensions of the literary work. According to Schiller, you are "at play" and by such playing in the fields of art and beauty, you are free.

And where does such play and spontaneous creativity ultimately lead? Schiller's philosophy is not art-for-art's sake, but art for the sake of morality and freedom and truth. If Schiller could wave a magic wand, everybody in society would receive an education in beauty by way of art, literature and music. And such education would ultimately nurture a population of men and women with highly developed aesthetic and moral sensibilities who could experience the full breathe and depth of what it means to be alive. Or, to put it another way, with a restored balance, harmony and character, people would no longer be slaves to the little world of their gut or the restricted world of their head, but would open their hearts and directly experience the fullness of life. And experiencing the fullness of life, for Schiller, is true freedom.

How realistic is Schiller's educational program as a way of transforming society? Perhaps being realistic is not exactly the issue. After all, Frederick Schiller was an idealist. He desired to see a society of men and women appreciating art and beauty and having their aesthetic appreciation color everyday behavior, so much so that their dealings and activity in the world would serve as a model of noble, moral conduct for all ages. Not a bad vision.

Poetry, Language, Thought by Albert Hofstadter, Martin Heidegger

Seven essays on poetry and the arts from German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) are collected here, including his key work on aesthetics, The Origin of a Work of Art. However, for the purposes of this review I will focus on his less well-known essay, What Are Poets For?” Here are several direct Heidegger quotes followed by my micro-fiction serving as a tribute to what I take to be much of the spirit of this essay:

“Being, which holds all beings in the balance, thus always draws particular beings toward itself – toward itself at the center.”

“Everything that is ventured is, as such and such a being, admitted into the whole of beings, and reposes in the ground of the whole.”

“The widest orbit of beings becomes present in the heart’s inner space. The whole of the world achieves here an equally essential presence in all its drawings.”

“The objectness of the world remains reckoned in that manner of representation which deals with time and space as quanta of calculation, and which can know no more of the nature of time than of the nature of space.”

“The conversion of consciousness is an inner recalling of the immanence of the objects of representation into presence within the heart’s space.”

-------------------

THE POETRY BAR

Thirsty, I enter a bar that’s dark, smoky and crowded, squeeze through and perch on a bar stool at the end closest the door, cross my arms on the counter and scan the faces of those around me. Many of the people are reading from sheets of paper, some reading silently, some muttering words aloud and still others reading to one another. The bartender approaches and asks me what I want, to which I, in turn, ask what he has on tap.

The bartender replies, “Most anything – Byron, Blake, Stevens, Frost, Browning, William Carlos Williams, you name it.”

So, it’s poetry rather than beer. I’m still thirsty but at least for now I tell him that I’ll take a Frost. The bartender obliges by handing me a copy of ‘Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening’.

I read the first stanza quickly then take my time reading the next three. I pause and look over at one of the crowded booths: six men with beards and black T-shirts are huddled together listening as their leader reads aloud from what I recognized as Alan Ginsburg’s ‘Howl’. The bartender was right – they do have most everything here.

I bend my head and begin to reread the first stanza of Frost when I hear great sobs from across the bar. A man with a ruddy complexion and a Scottish brogue is trying to recite Robert Burns but is having trouble because he keeps breaking down and crying. Another patron knocks roughly against me and then staggers through the door. Looking out the large front window I watch as he crosses the street, oblivious to cars and busses, as if lifted out of himself by an otherworldly ecstasy.

The bartender taps me on the elbow. When I turn he nods knowingly and tells me he always tries his best to keep an eye on anyone overdoing it.

5.0

Seven essays on poetry and the arts from German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) are collected here, including his key work on aesthetics, The Origin of a Work of Art. However, for the purposes of this review I will focus on his less well-known essay, What Are Poets For?” Here are several direct Heidegger quotes followed by my micro-fiction serving as a tribute to what I take to be much of the spirit of this essay:

“Being, which holds all beings in the balance, thus always draws particular beings toward itself – toward itself at the center.”

“Everything that is ventured is, as such and such a being, admitted into the whole of beings, and reposes in the ground of the whole.”

“The widest orbit of beings becomes present in the heart’s inner space. The whole of the world achieves here an equally essential presence in all its drawings.”

“The objectness of the world remains reckoned in that manner of representation which deals with time and space as quanta of calculation, and which can know no more of the nature of time than of the nature of space.”

“The conversion of consciousness is an inner recalling of the immanence of the objects of representation into presence within the heart’s space.”

-------------------

THE POETRY BAR

Thirsty, I enter a bar that’s dark, smoky and crowded, squeeze through and perch on a bar stool at the end closest the door, cross my arms on the counter and scan the faces of those around me. Many of the people are reading from sheets of paper, some reading silently, some muttering words aloud and still others reading to one another. The bartender approaches and asks me what I want, to which I, in turn, ask what he has on tap.

The bartender replies, “Most anything – Byron, Blake, Stevens, Frost, Browning, William Carlos Williams, you name it.”

So, it’s poetry rather than beer. I’m still thirsty but at least for now I tell him that I’ll take a Frost. The bartender obliges by handing me a copy of ‘Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening’.

I read the first stanza quickly then take my time reading the next three. I pause and look over at one of the crowded booths: six men with beards and black T-shirts are huddled together listening as their leader reads aloud from what I recognized as Alan Ginsburg’s ‘Howl’. The bartender was right – they do have most everything here.

I bend my head and begin to reread the first stanza of Frost when I hear great sobs from across the bar. A man with a ruddy complexion and a Scottish brogue is trying to recite Robert Burns but is having trouble because he keeps breaking down and crying. Another patron knocks roughly against me and then staggers through the door. Looking out the large front window I watch as he crosses the street, oblivious to cars and busses, as if lifted out of himself by an otherworldly ecstasy.

The bartender taps me on the elbow. When I turn he nods knowingly and tells me he always tries his best to keep an eye on anyone overdoing it.

Hop-Frog by Edgar Allan Poe

Love and Revenge – among the most intense, powerful, all-consuming passions in the entire range of human experience. I just did finish Jo Nesbø's The Son, a novel fueled by high octane love and revenge, enough revenge that when a reader turns the book’s last page, the tally of corpses for the morgue runs in double digits. Curiously enough, Nesbø’s novel reminded me of another tale of love and revenge, a classic, one penned by the inventor of the modern revenge tale, Edgar Allan Poe, a tale about a dwarf in the court of a medieval king, a tale with the title Hop-Frog.

The narrator begins by saying he never knew anybody who appreciated a joke as much as the king, a fat, jolly king who’s central reason for living was joking, so much so he surrounded himself with seven equally fat ministers who were accomplished jokers. And, as to the variety of jokes the king most enjoyed, well, the coarser the better, more specifically, coarse jokes that made fun, nay, humiliated and degraded others, and, to add more spice to his fun, if such humiliation and degradation mixed with a good dose of sadism, well, now that would really and truly be funny.

So, recognizing his taste for coarse, sadistic humor, this oh so jolly king had a special variety of jester at his court – a three-in-one object of ridicule, since his jester was not only a funny fatso but also, as the narrator describes, a dwarf and a cripple, a jester by the name of Hop-Frog, so named since Hop-Frog didn’t walk, rather this pint-sized fatso could only move by awkward, jerking jumps. And, for even greater kicks and jollies, the king also kept a second dwarf, a graceful young girl by the name of Trippetta. What fun! And, not surprisingly, emotionally bonded in their common plight, Trippetta and Hop-Frog became fast friends.

Let’s pause to reflect on a few similarities between Poe’s tale and Nesbø’s novel. Both feature a protagonist not only violated but, even more extreme, dehumanized; both tale and novel feature a sadistic villain; and, lastly, both feature a protagonist’s love for another. And these three common themes appear in abundance in Dark Arrows: Great Stories of Revenge anthologized by Alberto Manguel, featuring such tales as The Squaw by Bram Stoker, Emma Zunz by Jorge Luis Borges and A Bear Hunt by William Faulkner. The reason I reference these tales is to underscore the power such a narrative line has for readers – via the magic of literature, we live through the emotions of the violated extracting their revenge and rescuing the love of their life – a deeply moving experience.

Back on Poe’s tale. The king hosts a masquerade ball but is in a quandary: what should he himself do to be original? Events transpire leading Hop-Frog to offer a suggestion: a party of eight can enter the masquerade as escaped wild orangutans. The king jumps at the suggestion – he and his seven ministers will do it!

Such costumed extravaganzas are part of the historic record – case in point: in France during the 14th century, a young French king and his five nobleman buddies covered themselves with tar, flax and animal hair and, taking the role of wood savages, entered a room of masqueraders. The wood savages hooted and howled to everyone’s delight but disaster of disasters: a masquerader's torch came too close – several wood savages caught fire and burned alive. Will a similar fate befall the king and his seven ministers? Read this Poe tale (link below) to find out. And please let this review serve as a double recommendation – one recommendation for Poe’s tale and one for Jo Nesbø’s novel. Revenge doesn’t get any sweeter.

http://poestories.com/read/hop-frog

5.0

Love and Revenge – among the most intense, powerful, all-consuming passions in the entire range of human experience. I just did finish Jo Nesbø's The Son, a novel fueled by high octane love and revenge, enough revenge that when a reader turns the book’s last page, the tally of corpses for the morgue runs in double digits. Curiously enough, Nesbø’s novel reminded me of another tale of love and revenge, a classic, one penned by the inventor of the modern revenge tale, Edgar Allan Poe, a tale about a dwarf in the court of a medieval king, a tale with the title Hop-Frog.

The narrator begins by saying he never knew anybody who appreciated a joke as much as the king, a fat, jolly king who’s central reason for living was joking, so much so he surrounded himself with seven equally fat ministers who were accomplished jokers. And, as to the variety of jokes the king most enjoyed, well, the coarser the better, more specifically, coarse jokes that made fun, nay, humiliated and degraded others, and, to add more spice to his fun, if such humiliation and degradation mixed with a good dose of sadism, well, now that would really and truly be funny.

So, recognizing his taste for coarse, sadistic humor, this oh so jolly king had a special variety of jester at his court – a three-in-one object of ridicule, since his jester was not only a funny fatso but also, as the narrator describes, a dwarf and a cripple, a jester by the name of Hop-Frog, so named since Hop-Frog didn’t walk, rather this pint-sized fatso could only move by awkward, jerking jumps. And, for even greater kicks and jollies, the king also kept a second dwarf, a graceful young girl by the name of Trippetta. What fun! And, not surprisingly, emotionally bonded in their common plight, Trippetta and Hop-Frog became fast friends.

Let’s pause to reflect on a few similarities between Poe’s tale and Nesbø’s novel. Both feature a protagonist not only violated but, even more extreme, dehumanized; both tale and novel feature a sadistic villain; and, lastly, both feature a protagonist’s love for another. And these three common themes appear in abundance in Dark Arrows: Great Stories of Revenge anthologized by Alberto Manguel, featuring such tales as The Squaw by Bram Stoker, Emma Zunz by Jorge Luis Borges and A Bear Hunt by William Faulkner. The reason I reference these tales is to underscore the power such a narrative line has for readers – via the magic of literature, we live through the emotions of the violated extracting their revenge and rescuing the love of their life – a deeply moving experience.

Back on Poe’s tale. The king hosts a masquerade ball but is in a quandary: what should he himself do to be original? Events transpire leading Hop-Frog to offer a suggestion: a party of eight can enter the masquerade as escaped wild orangutans. The king jumps at the suggestion – he and his seven ministers will do it!

Such costumed extravaganzas are part of the historic record – case in point: in France during the 14th century, a young French king and his five nobleman buddies covered themselves with tar, flax and animal hair and, taking the role of wood savages, entered a room of masqueraders. The wood savages hooted and howled to everyone’s delight but disaster of disasters: a masquerader's torch came too close – several wood savages caught fire and burned alive. Will a similar fate befall the king and his seven ministers? Read this Poe tale (link below) to find out. And please let this review serve as a double recommendation – one recommendation for Poe’s tale and one for Jo Nesbø’s novel. Revenge doesn’t get any sweeter.

http://poestories.com/read/hop-frog

The Masque of the Red Death by Edgar Allan Poe

I’ve always sensed a strong connection to Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death, perhaps because I've both played and listen to loads of medieval music, perhaps because I enjoy the art and history and philosophy of that period, or, perhaps because I’ve always been drawn to literature dealing with issues of life and death. Whatever the reason, I love this tale. Here are my reflections on several themes:

THE REALITY

The tale’s Red Death sounds like the Black Death of 1349 where a family member could be perfectly healthy in the morning, start feeling sick at noon, spit blood and be in excruciating pain in the evening and be dead by midnight. It was that quick. Living at the time of the Black Death, one Italian chronicler wrote, “They died by the hundreds, both day and night, and all were thrown in ... ditches and covered with earth. And as soon as those ditches were filled, more were dug. And I, Agnolo di Tura ... buried my five children with my own hands ... And so many died that all believed it was the end of the world.”

THE DENIAL

Let the Red Death take those on the outside. Prince Prospero took steps to make sure his castle would be a sanctuary, a secure refuge where, once bolted inside, amid a carefully constructed world of festival, a thousand choice friends could revel in merriment with jugglers, musicians, dancers and an unlimited supply of wine. And then, “It was toward the close of the fifth or sixth month of his seclusion, and while the pestilence raged most furiously abroad, that the Prince Prospero entertained his thousand friends at a masked ball of the most unusual magnificence. It was a voluptuous scene, that masquerade.” Classic Edgar Allan Poe foreshadowing.

THE NUMBER SEVEN

The prince constructed seven rooms for his revelers. And there is all that medieval symbolism for the number seven, such as seven gifts of the holy spirit, Seven Seals from the Book of Revelation, seven liberal arts, the seven virtues and, of course, the seven deadly sins (gluttony, lechery, avarice, luxury, wrath, envy, and sloth), which sounds like a catalogue of activities within the castle walls.

THE SEVENTH ROOM - THE BLACK CHAMBER

Keeping in mind the medieval symbolism for the color black with associations of darkness, evil, the devil, power and secrecy, we read, “But in the western or black chamber the effect of the fire light that streamed upon the dark hangings through the blood-tinted panes, was ghastly in the extreme, and produced so wild a look upon the countenances of those who entered, that there were few of the company bold enough to set foot within its precincts at all.” We are told the prince’s plans were bold and fiery and barbaric, but, as we read the tale, we see how even a powerful prince can be outflanked by the fiery and chaotic side of life itself.

THE CLOCK

This seventh chamber has a huge ebony clanging clock. A reminder for both eye and ear that the prince can supply his revelers and himself with an unlimited supply of wine but there is one thing he doesn’t have the power to provide – an unlimited amount of time.

THE UNEXPECTED MASKER

When the clock clangs twelve times, a tall, gaunt, blood-spotted, corpse-like reveler appears in the black chamber. Poe, master storyteller that he is, pens one of my all-time favorite lines: “Even with the utterly lost, to whom life and death are equally jests, there are matters of which no jest can be made.” Not a lot of merriment once the revelers start dropping like blood-covered, despairing flies.

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL TALE

We read how there are some who think the prince mad. After all, what is a Poe tale without the possibility of madness? Additionally, when the revelers attempt to seize the intruder with his grey garments and corpse-like mask, they come away with nothing. If these revelers were minutes from an agonizing plague-induced death, how sharp are their senses, really? To what extent is their experience the play of the mind?

5.0

I’ve always sensed a strong connection to Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death, perhaps because I've both played and listen to loads of medieval music, perhaps because I enjoy the art and history and philosophy of that period, or, perhaps because I’ve always been drawn to literature dealing with issues of life and death. Whatever the reason, I love this tale. Here are my reflections on several themes:

THE REALITY

The tale’s Red Death sounds like the Black Death of 1349 where a family member could be perfectly healthy in the morning, start feeling sick at noon, spit blood and be in excruciating pain in the evening and be dead by midnight. It was that quick. Living at the time of the Black Death, one Italian chronicler wrote, “They died by the hundreds, both day and night, and all were thrown in ... ditches and covered with earth. And as soon as those ditches were filled, more were dug. And I, Agnolo di Tura ... buried my five children with my own hands ... And so many died that all believed it was the end of the world.”

THE DENIAL

Let the Red Death take those on the outside. Prince Prospero took steps to make sure his castle would be a sanctuary, a secure refuge where, once bolted inside, amid a carefully constructed world of festival, a thousand choice friends could revel in merriment with jugglers, musicians, dancers and an unlimited supply of wine. And then, “It was toward the close of the fifth or sixth month of his seclusion, and while the pestilence raged most furiously abroad, that the Prince Prospero entertained his thousand friends at a masked ball of the most unusual magnificence. It was a voluptuous scene, that masquerade.” Classic Edgar Allan Poe foreshadowing.

THE NUMBER SEVEN

The prince constructed seven rooms for his revelers. And there is all that medieval symbolism for the number seven, such as seven gifts of the holy spirit, Seven Seals from the Book of Revelation, seven liberal arts, the seven virtues and, of course, the seven deadly sins (gluttony, lechery, avarice, luxury, wrath, envy, and sloth), which sounds like a catalogue of activities within the castle walls.

THE SEVENTH ROOM - THE BLACK CHAMBER

Keeping in mind the medieval symbolism for the color black with associations of darkness, evil, the devil, power and secrecy, we read, “But in the western or black chamber the effect of the fire light that streamed upon the dark hangings through the blood-tinted panes, was ghastly in the extreme, and produced so wild a look upon the countenances of those who entered, that there were few of the company bold enough to set foot within its precincts at all.” We are told the prince’s plans were bold and fiery and barbaric, but, as we read the tale, we see how even a powerful prince can be outflanked by the fiery and chaotic side of life itself.

THE CLOCK

This seventh chamber has a huge ebony clanging clock. A reminder for both eye and ear that the prince can supply his revelers and himself with an unlimited supply of wine but there is one thing he doesn’t have the power to provide – an unlimited amount of time.

THE UNEXPECTED MASKER

When the clock clangs twelve times, a tall, gaunt, blood-spotted, corpse-like reveler appears in the black chamber. Poe, master storyteller that he is, pens one of my all-time favorite lines: “Even with the utterly lost, to whom life and death are equally jests, there are matters of which no jest can be made.” Not a lot of merriment once the revelers start dropping like blood-covered, despairing flies.

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL TALE

We read how there are some who think the prince mad. After all, what is a Poe tale without the possibility of madness? Additionally, when the revelers attempt to seize the intruder with his grey garments and corpse-like mask, they come away with nothing. If these revelers were minutes from an agonizing plague-induced death, how sharp are their senses, really? To what extent is their experience the play of the mind?

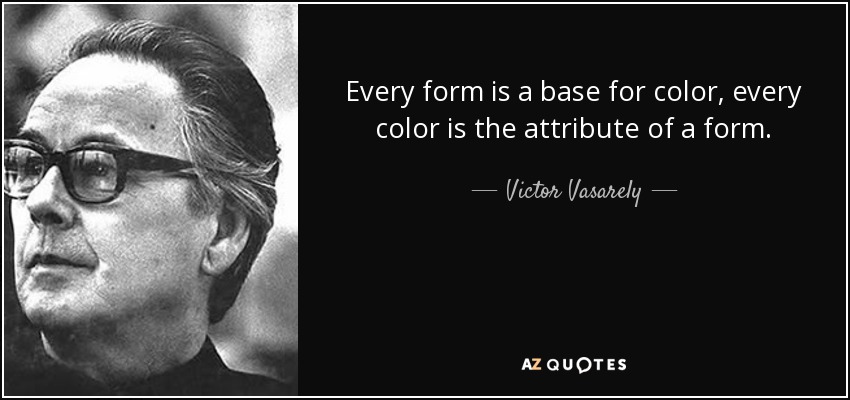

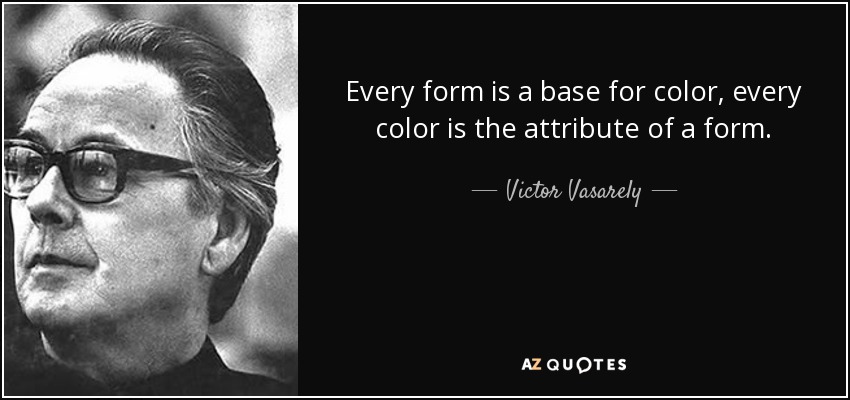

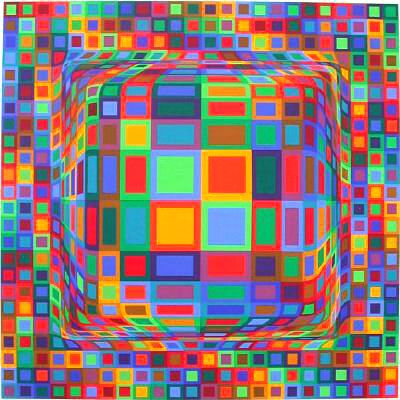

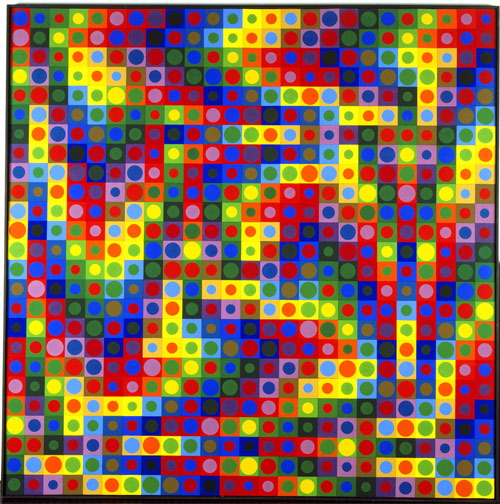

Vasarely by Gaston Diehl

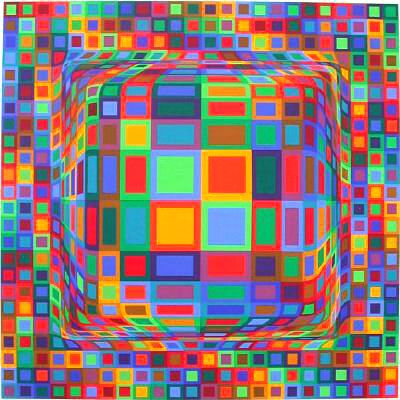

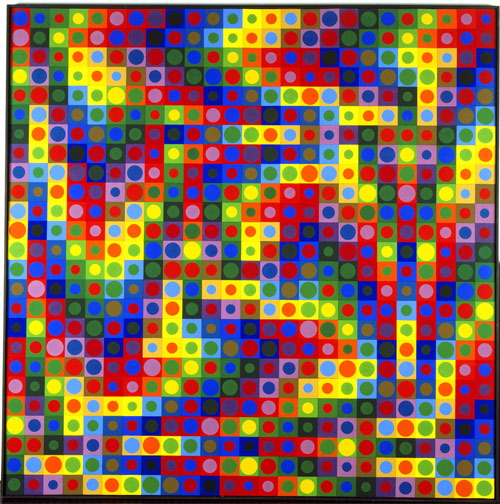

This handsome coffee table book by Gaston Diehl on the art and life of Hungarian-French artist Victor Vasarely (1906-1997) is a real find. The quality of seventy Vasarely prints (nearly all displayed on a full page and in color) is excellent. Also, art historian Gaston Diehl provides an insightful twenty-page overview of Vasarely's artistic evolution from a successful graphic artist in his twenties, an artist who, to use Vasarely's own words, went down the wrong track by producing works in the styles of the day - cubism, expressionism, futurism, symbolism, surrealism - until age forty, the time when he found his true creative self and hit his visual stride in geometric abstract art, or, what has come to be known as Op Art. Victor Vasarely also became a pioneer in the field of Kinetic Art.

Diehl provides detail of how the artist developed a unique geometric style over many years of trial and error. We read: "To accomplish harmonious compositions and unique constructive solutions, he constantly attempts to situate forms and colors on the plane surface; to purify both in order to obtain an economy of means and a total simplification, which are not however an impoverishment, as he emphasizes in his reflections; and lastly, to organize a rhythmic, balanced concatenation which suggests both a different space and a movement in gestation."

From my own experience, this is what I see when looking at Vasarely's geometrical shapes: purity and rhythm and balance as the clear forms and vivid colors seem to play with one another; it is as if I am transported to a completely free, completely open, non-temporal visual realm. If this sounds mystical, there’s good reason, it is mystical. As Diehl explains, Valarely engaged in "transformation of the external vision into an internal vision".

Here is another quote from Diehl underscoring the transcendent quality of Vasarely's geometric art: "The subtle dislocations arranged, and the numerous sharp angles, give the composition an appearance that is intermediate between pure spirituality and nature; that is: they lead to a geometry made all the more vivid by the fact that the force of the contrasts emphasizes its radiating luminosity."

I recall viewing an exhibition of Vasarely art and sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art some years back. I didn't want to leave. The combinations of colors and forms were so powerful and magnetic my eyes couldn't get enough Here are my brief comments on works from two prints in the book:

VEGA-WA-3

We have the geometry of circles, twenty-three circles on the vertical and twenty-two on the horizontal for a total of five-hundred-and-six circles, but these circles are not simply static, rather, the circles bulge out at the center, as if the vinyl canvas is a flexible rubber sheet and a ball is being pushed from the rear toward the viewer creating the illusion of three-dimensionality. The circles on the left are black on a burnt orange background and the circles on the right are light gray on a black background and as the shapes change via the pushed ball so the color of both the circles and background change into one another - a unique metamorphosis, the cross-transformation of both color and form.

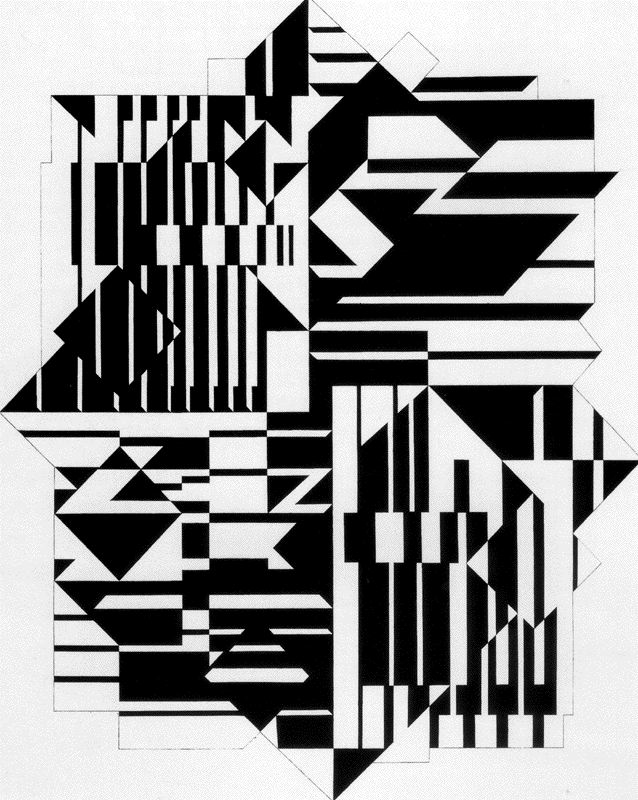

TAYMIR

A study in black-and-white, the artist has rectangles, triangles, parallelograms and squares overlapping one another in dazzling combinations, the overlap changing the shapes from white to black and from black to white or enlarging or shrinking the black-and-white design. Many of the squares are actually diamonds, standing on one of their corners. How many overlaps and combinations? Dozens and dozens and dozens. If you enjoy art of this type, you will find something new and fascinating with every viewing.

I don't know if I will ever have the opportunity to go to one of the Victor Vasarely museums in France or Hungary, but meanwhile there are a number of excellent books, including this one published by Crown Art Library.

Just for the fun of it, more art from this spectacular artist:

5.0

This handsome coffee table book by Gaston Diehl on the art and life of Hungarian-French artist Victor Vasarely (1906-1997) is a real find. The quality of seventy Vasarely prints (nearly all displayed on a full page and in color) is excellent. Also, art historian Gaston Diehl provides an insightful twenty-page overview of Vasarely's artistic evolution from a successful graphic artist in his twenties, an artist who, to use Vasarely's own words, went down the wrong track by producing works in the styles of the day - cubism, expressionism, futurism, symbolism, surrealism - until age forty, the time when he found his true creative self and hit his visual stride in geometric abstract art, or, what has come to be known as Op Art. Victor Vasarely also became a pioneer in the field of Kinetic Art.

Diehl provides detail of how the artist developed a unique geometric style over many years of trial and error. We read: "To accomplish harmonious compositions and unique constructive solutions, he constantly attempts to situate forms and colors on the plane surface; to purify both in order to obtain an economy of means and a total simplification, which are not however an impoverishment, as he emphasizes in his reflections; and lastly, to organize a rhythmic, balanced concatenation which suggests both a different space and a movement in gestation."

From my own experience, this is what I see when looking at Vasarely's geometrical shapes: purity and rhythm and balance as the clear forms and vivid colors seem to play with one another; it is as if I am transported to a completely free, completely open, non-temporal visual realm. If this sounds mystical, there’s good reason, it is mystical. As Diehl explains, Valarely engaged in "transformation of the external vision into an internal vision".

Here is another quote from Diehl underscoring the transcendent quality of Vasarely's geometric art: "The subtle dislocations arranged, and the numerous sharp angles, give the composition an appearance that is intermediate between pure spirituality and nature; that is: they lead to a geometry made all the more vivid by the fact that the force of the contrasts emphasizes its radiating luminosity."

I recall viewing an exhibition of Vasarely art and sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art some years back. I didn't want to leave. The combinations of colors and forms were so powerful and magnetic my eyes couldn't get enough Here are my brief comments on works from two prints in the book:

VEGA-WA-3

We have the geometry of circles, twenty-three circles on the vertical and twenty-two on the horizontal for a total of five-hundred-and-six circles, but these circles are not simply static, rather, the circles bulge out at the center, as if the vinyl canvas is a flexible rubber sheet and a ball is being pushed from the rear toward the viewer creating the illusion of three-dimensionality. The circles on the left are black on a burnt orange background and the circles on the right are light gray on a black background and as the shapes change via the pushed ball so the color of both the circles and background change into one another - a unique metamorphosis, the cross-transformation of both color and form.

TAYMIR

A study in black-and-white, the artist has rectangles, triangles, parallelograms and squares overlapping one another in dazzling combinations, the overlap changing the shapes from white to black and from black to white or enlarging or shrinking the black-and-white design. Many of the squares are actually diamonds, standing on one of their corners. How many overlaps and combinations? Dozens and dozens and dozens. If you enjoy art of this type, you will find something new and fascinating with every viewing.

I don't know if I will ever have the opportunity to go to one of the Victor Vasarely museums in France or Hungary, but meanwhile there are a number of excellent books, including this one published by Crown Art Library.

Just for the fun of it, more art from this spectacular artist:

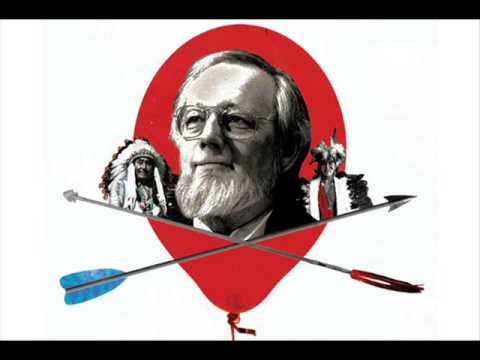

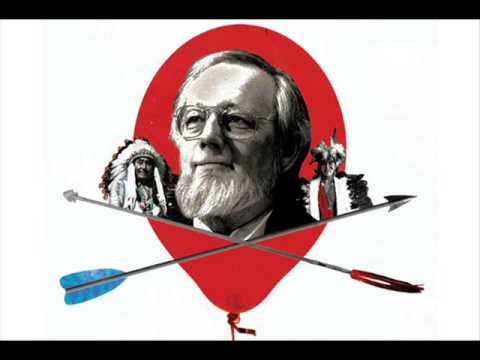

The Indian Uprising by Donald Barthelme

The Indian Uprising is among the most popular of Donald Barthelme’s stories, one I included as part of another review, but I truly love this highly perceptive, highly philosophical work of short fiction so much, I judge the story worthy of its own review. Here are a number of themes I see contained in its mere seven pages:

America, land of genocide

Why are Indians attacking an American city in the 20th century? Why are the narrator’s people defending the city? Is this a mental defending of past history, a defending or justifying the genocide of the Native Americans in previous centuries? Back in high school history class during the late 1960s, the time this story was written, there wasn’t too much said about the brutal treatment of Native Americans and the destruction of their populations and cultures. Ironically, my high school mascot was and still is “The Indians.”

America the superficial

“There were earthworks along the Boulevard Mark Clark and the hedges had been laced with sparkling wire.” Nice contrast, Donald: the Indians and their primitive crafts (earthworks) on one side and the barbed wire (sparkling wire) on the other. Donald Barthelme doesn’t miss an opportunity to make his story’s details, telling details – case in point, barbed wire played a pivotal role in transforming the open land west of the Mississippi River into domesticated ranchland. Meanwhile, the narrator, let’s call him Bob, asks his girlfriend Silvia if this is a good life. She tell him “No.” Are the apples, books and long-playing records laid out on a table (perhaps symbols of American, the land of plenty), Bob’s idea of a good life, even if his city is under attack? If so, Bob’s idea of the good life sounds rather superficial.

America the hyper-violent

Bob and others torture a Comanche but Bob doesn’t give this cruel act any more emotional weight than if he and a couple men were cleaning up a grimy picnic table. I don’t know about you, but such insensitivity and sadism sends shivers up my spine. In the late 1960s, the time when this story was first published, photographs of Americans torturing Vietnamese first began appearing fairly regularly in magazines and newspapers. Additionally, I recall how during the late 1960s , Saturday morning cartoons switched from funny to hyper-violent, which caused outrage among some to ask: “Are we becoming a country of extreme violence and nothing but extreme violence?”

America, land of postmodern leveling

Bob asks Silvia if she is familiar with the classical composer Gabriel Fauré. This question quickly shifts to Bob’s reflections on the details of a smut scene and then to the tables he made for four different women. This mental jumping from the beautiful to the repugnant, from people to objects, treating everything, irrespective of content, with the same emotional neutrality sounds like a grotesque form of postmodern leveling. Personally, this is one big reason I have always refused to watch commercial television: the non-stop switching from one image to the next, from tragedy on the nightly news to selling candy bars to the latest insurance deal I find unsettling in the extreme.

America, land of the racist

Bob tells us: “Red men in waves like people, scattering in a square startled by something tragic or a sudden, loud noise accumulated against the barricade we had made of window dummies, silk, thoughtfully planned job descriptions (including scales for the orderly progress of other colors), wine in demijohns, and robes.” Red men in waves like people? They are people! Stupid to the core, Bob blithely dehumanizes others by his racism and barely realizes he is doing so. Donald Barthelme wrote this with a light touch, but I couldn’t imagine an author damning his own society and culture with more vitriol and scorn. John Gardner wrote how Barthelme lacked a moral sense. What the hell were you thinking, John?!

America, the land of hard drugs

To combat the uprising, Bob notes: “We sent more heroin into the ghetto.” And the emphasis is on “more” since it is well documented how the U.S. government permitted and even encouraged the influx of hard drugs into poor black neighborhoods. Ironically, the outrage over the widespread use of hard drugs began once drug usage and addiction entered the fabric of middle class suburbia. I don’t think I’m alone in detecting a direct link between the use of drugs -- hard drugs, prescription drugs, recreational drugs - and the emotional numbness people have to the ocean of detritus overwhelming their lives.

America, the land of booze and passion

Bob actively participates in more extreme torture. Doesn’t bother Bob in the least. Bob simply gets more and more drunk and falls more and more in love. Even when he hears children have been killed in masses, Bob barely reacts. Have some more booze, Bob, as that will solve all your problems. All this Bob stuff occurring in a world where, “The officer commanding the garbage dump reported by radio that the garbage had begun to move.” Also, “Strings of language extend in every direction to bind the world into a rushing, ribald whole.” Have another drink, Bob, and convince yourself you are falling more and more in love.

The Indian Uprising can be accessed via a Google search. The story also appears in the author's Sixty Stories.

5.0

The Indian Uprising is among the most popular of Donald Barthelme’s stories, one I included as part of another review, but I truly love this highly perceptive, highly philosophical work of short fiction so much, I judge the story worthy of its own review. Here are a number of themes I see contained in its mere seven pages:

America, land of genocide

Why are Indians attacking an American city in the 20th century? Why are the narrator’s people defending the city? Is this a mental defending of past history, a defending or justifying the genocide of the Native Americans in previous centuries? Back in high school history class during the late 1960s, the time this story was written, there wasn’t too much said about the brutal treatment of Native Americans and the destruction of their populations and cultures. Ironically, my high school mascot was and still is “The Indians.”

America the superficial

“There were earthworks along the Boulevard Mark Clark and the hedges had been laced with sparkling wire.” Nice contrast, Donald: the Indians and their primitive crafts (earthworks) on one side and the barbed wire (sparkling wire) on the other. Donald Barthelme doesn’t miss an opportunity to make his story’s details, telling details – case in point, barbed wire played a pivotal role in transforming the open land west of the Mississippi River into domesticated ranchland. Meanwhile, the narrator, let’s call him Bob, asks his girlfriend Silvia if this is a good life. She tell him “No.” Are the apples, books and long-playing records laid out on a table (perhaps symbols of American, the land of plenty), Bob’s idea of a good life, even if his city is under attack? If so, Bob’s idea of the good life sounds rather superficial.

America the hyper-violent

Bob and others torture a Comanche but Bob doesn’t give this cruel act any more emotional weight than if he and a couple men were cleaning up a grimy picnic table. I don’t know about you, but such insensitivity and sadism sends shivers up my spine. In the late 1960s, the time when this story was first published, photographs of Americans torturing Vietnamese first began appearing fairly regularly in magazines and newspapers. Additionally, I recall how during the late 1960s , Saturday morning cartoons switched from funny to hyper-violent, which caused outrage among some to ask: “Are we becoming a country of extreme violence and nothing but extreme violence?”

America, land of postmodern leveling

Bob asks Silvia if she is familiar with the classical composer Gabriel Fauré. This question quickly shifts to Bob’s reflections on the details of a smut scene and then to the tables he made for four different women. This mental jumping from the beautiful to the repugnant, from people to objects, treating everything, irrespective of content, with the same emotional neutrality sounds like a grotesque form of postmodern leveling. Personally, this is one big reason I have always refused to watch commercial television: the non-stop switching from one image to the next, from tragedy on the nightly news to selling candy bars to the latest insurance deal I find unsettling in the extreme.

America, land of the racist

Bob tells us: “Red men in waves like people, scattering in a square startled by something tragic or a sudden, loud noise accumulated against the barricade we had made of window dummies, silk, thoughtfully planned job descriptions (including scales for the orderly progress of other colors), wine in demijohns, and robes.” Red men in waves like people? They are people! Stupid to the core, Bob blithely dehumanizes others by his racism and barely realizes he is doing so. Donald Barthelme wrote this with a light touch, but I couldn’t imagine an author damning his own society and culture with more vitriol and scorn. John Gardner wrote how Barthelme lacked a moral sense. What the hell were you thinking, John?!

America, the land of hard drugs

To combat the uprising, Bob notes: “We sent more heroin into the ghetto.” And the emphasis is on “more” since it is well documented how the U.S. government permitted and even encouraged the influx of hard drugs into poor black neighborhoods. Ironically, the outrage over the widespread use of hard drugs began once drug usage and addiction entered the fabric of middle class suburbia. I don’t think I’m alone in detecting a direct link between the use of drugs -- hard drugs, prescription drugs, recreational drugs - and the emotional numbness people have to the ocean of detritus overwhelming their lives.

America, the land of booze and passion

Bob actively participates in more extreme torture. Doesn’t bother Bob in the least. Bob simply gets more and more drunk and falls more and more in love. Even when he hears children have been killed in masses, Bob barely reacts. Have some more booze, Bob, as that will solve all your problems. All this Bob stuff occurring in a world where, “The officer commanding the garbage dump reported by radio that the garbage had begun to move.” Also, “Strings of language extend in every direction to bind the world into a rushing, ribald whole.” Have another drink, Bob, and convince yourself you are falling more and more in love.

The Indian Uprising can be accessed via a Google search. The story also appears in the author's Sixty Stories.

The Magic Couch by Guy de Maupassant

Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893), universally recognized master of the short-story, is best known for such tales as The Diamond Necklace and The Piece of String, but if anybody would care to become more fully acquainted with the great author's sharp satiric sting and caustic bite, we can turn to The Magic Couch, a very short story of a wealthy Parisian bathing in the bright morning light of Paris, the crisp air, the lush trees, the beauty of the Seine, when he is handed the morning paper and reads the headline: over 8,500 people killed themselves this past year.

This headline and statistic prompts our well-to-do narrator to vividly visualize a number of grim scenes. We read, “In a moment I seemed to see them! I saw this voluntary and hideous massacre of the despairing who were weary of life. I saw men bleeding, their jaws fractured, their skulls cloven, their breasts pierced by a bullet, slowly dying, alone in a little room in a hotel, giving no thought to their wound, but thinking only of their misfortunes.”

And this is only the beginning: his imagination and visualizations become more lurid, explicit, shocking, grisly and morbid; so much so that he begins to dream in wild ways on the subject of suicide until he finds himself standing in front of the Parisian Suicide Bureau.

Quickly, very quickly, he enters the building and is immediately brought before the Secretary of the Bureau who is more than happy to answer all his questions. The Secretary goes on to tell him how the Bureau aids people wishing to die by putting them to death in a clean, gentle and perfectly agreeable manner. The narrator’s exchange with the Secretary becomes progressively more bizarre – he is told how all the suicides became an unending horror-show for all the people who loved life and also set a poor example for children. Something needed to be done. By government decree, suicides were centralized. The Secretary goes on to explain how the suicidal population makes its way to the Bureau and the day-to-day details of running his Bureau, including how a club was formed to oversee operations and how arrangements are made so club members experience maximum enjoyment.

For a grand finale, the Secretary invites the narrator into the suicide room reserved for club members. Everything is decorated and arranged to accord with the highest and most refined aesthetic tastes. The narrator accepts the Secretary’s offer to sample the fragrant, pleasurable asphyxiating gas. The narrator reflects, “A little uneasy I seated myself on the low couch covered with crepe de Chine and stretched myself full length, and was at once bathed in a delicious odor of mignonette. I opened my mouth in order to breathe it in, for my mind had already become stupefied and forgetful of the past and was a prey, in the first stages of asphyxia, to the enchanting intoxication of a destroying and magic opium.” At this point someone shakes his arm; he is awakened out of his dream by his servant, a servant who says he is off to see the body of someone who that very morning threw himself in the Seine.

So, let us pause and take stock of this Maupassant story. For starters, the story’s surrealism reminds me of a number of Franz Kafka’s fable-like tales. Also, what the narrator finds in the suicide bureau could easily be one of the rooms of the magic theater from Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf. I’m sure readers of modern literature will find in this tale echoes of a number of other stories and novels. What really strikes me is how sensitive artists and writers in the 19th century like Maupassant could clearly see the dire consequences of a society and civilization transformed from rural agrarian to urban industrial. Such a tale is a universe away from the scientific positivism of the day.

Back on the topic of suicide. This is one of the most sensitive and difficult subjects the modern world has had to wrestled with over the 100+ years since Maupassant wrote this tale. The fact that there are a large number of tragic suicides, particularly among the young and college-age population, speaks to spheres of human development and personality and economics we as a modern society have yet to adequately address.

Personally, I am reminded of the words of 19th century German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer: “Compare the impression made upon one by the news that a friend has committed a crime, say a murder, an act of cruelty or deception, or theft, with the news that he has died a voluntary death. Whilst news of the first kind will incite intense indignation, the greatest displeasure, and a desire for punishment or revenge, news of the second will move us to sorrow and compassion; moreover, we will frequently have a feeling of admiration for his courage rather than one of moral disapproval, which accompanies a wicked act. Who has not had acquaintances, friends, relatives, who have voluntarily left this world?”

As noted above, The Magic Couch is as relevant today as it was in Maupassant’s day. Here is a link for all of the tales of Guy de Maupassant. The Magic Couch is the last tale listed in volume XIII -- http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28076/...

"Get black on white.”

― Guy de Maupassant

5.0

Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893), universally recognized master of the short-story, is best known for such tales as The Diamond Necklace and The Piece of String, but if anybody would care to become more fully acquainted with the great author's sharp satiric sting and caustic bite, we can turn to The Magic Couch, a very short story of a wealthy Parisian bathing in the bright morning light of Paris, the crisp air, the lush trees, the beauty of the Seine, when he is handed the morning paper and reads the headline: over 8,500 people killed themselves this past year.

This headline and statistic prompts our well-to-do narrator to vividly visualize a number of grim scenes. We read, “In a moment I seemed to see them! I saw this voluntary and hideous massacre of the despairing who were weary of life. I saw men bleeding, their jaws fractured, their skulls cloven, their breasts pierced by a bullet, slowly dying, alone in a little room in a hotel, giving no thought to their wound, but thinking only of their misfortunes.”

And this is only the beginning: his imagination and visualizations become more lurid, explicit, shocking, grisly and morbid; so much so that he begins to dream in wild ways on the subject of suicide until he finds himself standing in front of the Parisian Suicide Bureau.

Quickly, very quickly, he enters the building and is immediately brought before the Secretary of the Bureau who is more than happy to answer all his questions. The Secretary goes on to tell him how the Bureau aids people wishing to die by putting them to death in a clean, gentle and perfectly agreeable manner. The narrator’s exchange with the Secretary becomes progressively more bizarre – he is told how all the suicides became an unending horror-show for all the people who loved life and also set a poor example for children. Something needed to be done. By government decree, suicides were centralized. The Secretary goes on to explain how the suicidal population makes its way to the Bureau and the day-to-day details of running his Bureau, including how a club was formed to oversee operations and how arrangements are made so club members experience maximum enjoyment.

For a grand finale, the Secretary invites the narrator into the suicide room reserved for club members. Everything is decorated and arranged to accord with the highest and most refined aesthetic tastes. The narrator accepts the Secretary’s offer to sample the fragrant, pleasurable asphyxiating gas. The narrator reflects, “A little uneasy I seated myself on the low couch covered with crepe de Chine and stretched myself full length, and was at once bathed in a delicious odor of mignonette. I opened my mouth in order to breathe it in, for my mind had already become stupefied and forgetful of the past and was a prey, in the first stages of asphyxia, to the enchanting intoxication of a destroying and magic opium.” At this point someone shakes his arm; he is awakened out of his dream by his servant, a servant who says he is off to see the body of someone who that very morning threw himself in the Seine.

So, let us pause and take stock of this Maupassant story. For starters, the story’s surrealism reminds me of a number of Franz Kafka’s fable-like tales. Also, what the narrator finds in the suicide bureau could easily be one of the rooms of the magic theater from Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf. I’m sure readers of modern literature will find in this tale echoes of a number of other stories and novels. What really strikes me is how sensitive artists and writers in the 19th century like Maupassant could clearly see the dire consequences of a society and civilization transformed from rural agrarian to urban industrial. Such a tale is a universe away from the scientific positivism of the day.

Back on the topic of suicide. This is one of the most sensitive and difficult subjects the modern world has had to wrestled with over the 100+ years since Maupassant wrote this tale. The fact that there are a large number of tragic suicides, particularly among the young and college-age population, speaks to spheres of human development and personality and economics we as a modern society have yet to adequately address.

Personally, I am reminded of the words of 19th century German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer: “Compare the impression made upon one by the news that a friend has committed a crime, say a murder, an act of cruelty or deception, or theft, with the news that he has died a voluntary death. Whilst news of the first kind will incite intense indignation, the greatest displeasure, and a desire for punishment or revenge, news of the second will move us to sorrow and compassion; moreover, we will frequently have a feeling of admiration for his courage rather than one of moral disapproval, which accompanies a wicked act. Who has not had acquaintances, friends, relatives, who have voluntarily left this world?”

As noted above, The Magic Couch is as relevant today as it was in Maupassant’s day. Here is a link for all of the tales of Guy de Maupassant. The Magic Couch is the last tale listed in volume XIII -- http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28076/...

"Get black on white.”

― Guy de Maupassant

Cathedral by Raymond Carver

American author Raymond Carver (1938-1988) - master of the short-story

A dozen Raymond Carver stories collected here as part of the 1980s Vintage Contemporaries series. Since other reviewers have commented on all twelve, I’ll share some short-short cuts from the title story, my reflections on Carver doozy, a story I dearly love. Here goes:

CATHEDRAL

The Blind Man: The narrator’s wife is bringing her old friend, a blind man, home for a visit since the blind man made the trip to Connecticut to visit relatives following the death of his wife. The narrator’s idea of blindness and what it means to be a blind man comes from the movies. Such a telling detail of lower-middle-class Carver country, life saturated by popular culture, especially movies and television. (Although the narrator remains nameless throughout the story, I sense his name is Al, so I’ll take the liberty to occasionally refer to the narrator as Al).

Poetry: Al’s wife writes poems, one such poem about how during her last session with the blind man, she let him touch her face and neck with his fingers. And Al’s reaction to poetry? “I admit it’s not the first thing I reach for when I pick up something to read.” Ha! What understatement – "not the first thing I reach for" - matter of fact, safe to say Al hasn’t come within a mile of reading a poem since high school English class. I can clearly envision Al rolling his eyes as he grumbles under his breath: "Damn sissy stuff."

Lifeless Bitter Pill: The narrator conveys some of his wife’s background, how she married her childhood sweetheart, etc. It’s that "et cetera" that underlines Al’s distaste for life. For Al, life is a bitter pill. Black bile Al. His words about his wife’s despair and attempted suicide before she met him are entirely devoid of emotion and as flat and as cold as a frozen pancake.

Recreation: Al’s wife has been trading tapes with the blind man over the years. Al demeans the tapes along with his wife’s poetry, calling them her chief means of recreation. At one point, listening to one of the tapes, Al does get extremely upset. We read: “My own name in the mouth of this stranger, this blind man I didn’t even know!” A key revealer of what Al really values and finds important as he sings that all too familiar song: “It’s all about me.”

Pathetic: The blind man lived with his wife and after she fell ill, had to sit by his wife’s side holding her hand in the hospital and then bury her when she died. “All this without his having ever seen what the goddamned woman looked like. It was beyond my understanding.” The narrator goes on to tell us how the blind man is left with a small insurance policy and half a Mexican coin. “The other half of the coin went into the box with her. Pathetic.” The perfect word since, ironically, what is truly pathetic is the narrator’s hard-boiled, heartless cynicism.

Creepy: As Al waits for his wife to return with the blind man from the station, what does he do? The two big pastimes in Carver country: drink and watch TV. When the blind man does arrive, the narrator is surprised he doesn’t use a cane or wear dark glasses. He looks carefully at Robert’s eyes (the blind man’s name is Robert) and conveys the detail of what he sees. His overarching observation: creepy.

Family Prayer: After a few snide, sarcastic questions and remarks hurled at Robert courtesy of our narrator as they smoke and drink in the living room, all three sit down at the table for dinner. Before they all dig in, we read: “Now let us pray.” I said, and the blind man lowered his head. My wife looked at me, her mouth agape. “Pray the phone won’t ring and the food doesn’t get cold.”” Raymond Carver, you sly dog, slipping this belly-laugher into your bleak tale. Actually, one thing that is not pathetic, even for black bile Al: serious eating. When all else fails, always the animal pleasure of chowing down on steak and potatoes and strawberry pie.

Rat Wheel: After-dinner conversation and Al finds out that Robert has done a little of everything (“a regular blind jack-of-all-trades”). In turn, Robert asks a few questions about Al's job and almost predictably the narrator’s answers are: 1) three years at present position, 2) don’t like it, and 3) no real options to get out. Work as a deadening reinforcement that life is an unending rat wheel. But the narrator has one surefire way to deal with the rat wheel: every night he smokes dope and stays up as long as he can.

TV and Dope to the Rescue: When the conversation peters out, TV to the rescue. Al turns on the set and his wife leaves to change into her nightgown and robe. Alone together, Al treats Robert to a little cannabis. When the narrator’s wife returns Robert tells her there is always a first time for everything. She takes a seat on the coach and joins them. As the narrator observes: the blind man was inhaling as if he has been smoking weed since he was nine.

The Creative Act: Al’s wife falls asleep on the coach and he and Robert watch a TV program about medieval cathedrals. The narrator questions Robert on how much he knows about cathedrals, just how big they are. Robert suggests they engage in a little artwork together so the narrator can show him all about cathedrals. Down on the living room carpet, armed with pen and paper, Al and Robert, hand on hand, begin their artwork. Then, the unexpected happens during their joint creativity. Robert tell the narrator to close his eyes and asks him what he thinks.

MU: The narrator says it is like nothing else in his life up to now; how he doesn’t feel like he’s inside anything. It’s really something. ----- My reading of the narrator's experience: He finally lets go of his self-preoccupation and crusty cynicism and has a direct experience of that other side of life, the one beyond ego, beyond judgements, beyond all categories, life as boundless awareness. In Zen, this is called Satori but for right now on his hands and knees on the living room carpet, it has no name and it needs no name.

Black Painting No. 34, 1964 by American Artist, Ad Reinhardt

5.0

American author Raymond Carver (1938-1988) - master of the short-story

A dozen Raymond Carver stories collected here as part of the 1980s Vintage Contemporaries series. Since other reviewers have commented on all twelve, I’ll share some short-short cuts from the title story, my reflections on Carver doozy, a story I dearly love. Here goes:

CATHEDRAL

The Blind Man: The narrator’s wife is bringing her old friend, a blind man, home for a visit since the blind man made the trip to Connecticut to visit relatives following the death of his wife. The narrator’s idea of blindness and what it means to be a blind man comes from the movies. Such a telling detail of lower-middle-class Carver country, life saturated by popular culture, especially movies and television. (Although the narrator remains nameless throughout the story, I sense his name is Al, so I’ll take the liberty to occasionally refer to the narrator as Al).

Poetry: Al’s wife writes poems, one such poem about how during her last session with the blind man, she let him touch her face and neck with his fingers. And Al’s reaction to poetry? “I admit it’s not the first thing I reach for when I pick up something to read.” Ha! What understatement – "not the first thing I reach for" - matter of fact, safe to say Al hasn’t come within a mile of reading a poem since high school English class. I can clearly envision Al rolling his eyes as he grumbles under his breath: "Damn sissy stuff."

Lifeless Bitter Pill: The narrator conveys some of his wife’s background, how she married her childhood sweetheart, etc. It’s that "et cetera" that underlines Al’s distaste for life. For Al, life is a bitter pill. Black bile Al. His words about his wife’s despair and attempted suicide before she met him are entirely devoid of emotion and as flat and as cold as a frozen pancake.

Recreation: Al’s wife has been trading tapes with the blind man over the years. Al demeans the tapes along with his wife’s poetry, calling them her chief means of recreation. At one point, listening to one of the tapes, Al does get extremely upset. We read: “My own name in the mouth of this stranger, this blind man I didn’t even know!” A key revealer of what Al really values and finds important as he sings that all too familiar song: “It’s all about me.”

Pathetic: The blind man lived with his wife and after she fell ill, had to sit by his wife’s side holding her hand in the hospital and then bury her when she died. “All this without his having ever seen what the goddamned woman looked like. It was beyond my understanding.” The narrator goes on to tell us how the blind man is left with a small insurance policy and half a Mexican coin. “The other half of the coin went into the box with her. Pathetic.” The perfect word since, ironically, what is truly pathetic is the narrator’s hard-boiled, heartless cynicism.

Creepy: As Al waits for his wife to return with the blind man from the station, what does he do? The two big pastimes in Carver country: drink and watch TV. When the blind man does arrive, the narrator is surprised he doesn’t use a cane or wear dark glasses. He looks carefully at Robert’s eyes (the blind man’s name is Robert) and conveys the detail of what he sees. His overarching observation: creepy.

Family Prayer: After a few snide, sarcastic questions and remarks hurled at Robert courtesy of our narrator as they smoke and drink in the living room, all three sit down at the table for dinner. Before they all dig in, we read: “Now let us pray.” I said, and the blind man lowered his head. My wife looked at me, her mouth agape. “Pray the phone won’t ring and the food doesn’t get cold.”” Raymond Carver, you sly dog, slipping this belly-laugher into your bleak tale. Actually, one thing that is not pathetic, even for black bile Al: serious eating. When all else fails, always the animal pleasure of chowing down on steak and potatoes and strawberry pie.

Rat Wheel: After-dinner conversation and Al finds out that Robert has done a little of everything (“a regular blind jack-of-all-trades”). In turn, Robert asks a few questions about Al's job and almost predictably the narrator’s answers are: 1) three years at present position, 2) don’t like it, and 3) no real options to get out. Work as a deadening reinforcement that life is an unending rat wheel. But the narrator has one surefire way to deal with the rat wheel: every night he smokes dope and stays up as long as he can.