Scan barcode

glenncolerussell's reviews

1456 reviews

The Background by Saki

The Fall of Icarus, Italian Late Mannerist and Early Baroque painter Giovanni Baglione (1566-1643)

French author Maurice Leblanc created dozens of provocative short stories featuring a gentleman thief and master of disguise by the name of Arsène Lupin. In a somewhat similar vein, by my reading, British author Hector Hugh Munro aka Saki (a name taken from the poetry of Omar Khayyam) wrote his short fiction featuring a narrator as refined aesthete, either telling his tale in objective third person or taking on the role of an actual character within the story itself.

As the Leblanc tales revolve around crime, so the Saki tales revolve around an aesthetic moment, usually touching directly or indirectly on art, music or literature or those other cultivated British arts: civilized conversation and social interchange. True, these Saki tales may include elements of satire and biting social commentary but they also contain great humor and wit rendered in highly polished, tasteful, elegant prose.

“That woman’s art-jargon tires me,” said Clovis to his journalist friend. “She’s so fond of talking of certain pictures as ‘growing on one,’ as though they were a sort of fungus.” So begins The Background, from Saki’s book, The Chronicles of Clovis, a stunning three-page tale where, prompted by Clovis’ statement, the journalist relates the story of one Henri Deplis, a native of Luxemburg who inherited a modest sum of money impelling him to a seemingly harmless bit of extravagant behavior when in Italy: he made his way to the tattoo parlor of Signor Andreas Pincini and for six hundred francs had his entire back covered with the artist’s version of The Fall of Icarus.

As the journalist continues, Signor Pincini died shortly thereafter and following some bad blood about monies owed for the tattoo, the artist’s widow donated The Fall of Icarus (considered her husband’s masterwork) to the city of Bergamo.

Events transpire against Henri Deplis: he is forced to leave a public sauna since the proprietor will not allow such a work to be placed on display, the Bergamo authorities prohibit Henri to expose his back in the sun so as to damage their art, he is even prevented from crossing the border since by law Italian works of art must remain in the country. Poor Henri! You will have to read for yourself to find out how the tale takes a few more unexpected, rather brutal twists (link below).

What a story; what a tattoo! I’m left with a question: If I had my own back covered with such a tattoo, what work of art would I choose. Of course this is only a fanciful “what if” since no tattoos for me, thank you. For starters, I am not a big fan of pain. However, if I were to imagine my back covered, what would be the tattoo? Well, as per below, I know three pieces of art I wouldn’t choose:

The middle panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights – If the tattoo artist also needled the left panel and right panel on two other willing subjects, in all likelihood, museum curators would insist all three of us tour together so the entire triptych could be placed on display.

The tiger shark from Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living - A really bad choice since I’d have to immerse myself up to the neck in a tank of formaldehyde to replicate the original.

Graphic Designer/Artist Joe Wezorek’s picture of 670 faces of soldiers who lost their lives in Iraq during George W. Bush’s war - I wouldn't want to carry such a powerful political statement around on my back.

What work of art would you choose? Link to The Background by Saki: http://www.eastoftheweb.com/short-stories/UBooks/Bac.shtml

“The young have aspirations that never come to pass, the old have reminiscences of what never happened.”

― Saki (1870 - 1916)

5.0

The Fall of Icarus, Italian Late Mannerist and Early Baroque painter Giovanni Baglione (1566-1643)

French author Maurice Leblanc created dozens of provocative short stories featuring a gentleman thief and master of disguise by the name of Arsène Lupin. In a somewhat similar vein, by my reading, British author Hector Hugh Munro aka Saki (a name taken from the poetry of Omar Khayyam) wrote his short fiction featuring a narrator as refined aesthete, either telling his tale in objective third person or taking on the role of an actual character within the story itself.

As the Leblanc tales revolve around crime, so the Saki tales revolve around an aesthetic moment, usually touching directly or indirectly on art, music or literature or those other cultivated British arts: civilized conversation and social interchange. True, these Saki tales may include elements of satire and biting social commentary but they also contain great humor and wit rendered in highly polished, tasteful, elegant prose.

“That woman’s art-jargon tires me,” said Clovis to his journalist friend. “She’s so fond of talking of certain pictures as ‘growing on one,’ as though they were a sort of fungus.” So begins The Background, from Saki’s book, The Chronicles of Clovis, a stunning three-page tale where, prompted by Clovis’ statement, the journalist relates the story of one Henri Deplis, a native of Luxemburg who inherited a modest sum of money impelling him to a seemingly harmless bit of extravagant behavior when in Italy: he made his way to the tattoo parlor of Signor Andreas Pincini and for six hundred francs had his entire back covered with the artist’s version of The Fall of Icarus.

As the journalist continues, Signor Pincini died shortly thereafter and following some bad blood about monies owed for the tattoo, the artist’s widow donated The Fall of Icarus (considered her husband’s masterwork) to the city of Bergamo.

Events transpire against Henri Deplis: he is forced to leave a public sauna since the proprietor will not allow such a work to be placed on display, the Bergamo authorities prohibit Henri to expose his back in the sun so as to damage their art, he is even prevented from crossing the border since by law Italian works of art must remain in the country. Poor Henri! You will have to read for yourself to find out how the tale takes a few more unexpected, rather brutal twists (link below).

What a story; what a tattoo! I’m left with a question: If I had my own back covered with such a tattoo, what work of art would I choose. Of course this is only a fanciful “what if” since no tattoos for me, thank you. For starters, I am not a big fan of pain. However, if I were to imagine my back covered, what would be the tattoo? Well, as per below, I know three pieces of art I wouldn’t choose:

The middle panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights – If the tattoo artist also needled the left panel and right panel on two other willing subjects, in all likelihood, museum curators would insist all three of us tour together so the entire triptych could be placed on display.

The tiger shark from Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living - A really bad choice since I’d have to immerse myself up to the neck in a tank of formaldehyde to replicate the original.

Graphic Designer/Artist Joe Wezorek’s picture of 670 faces of soldiers who lost their lives in Iraq during George W. Bush’s war - I wouldn't want to carry such a powerful political statement around on my back.

What work of art would you choose? Link to The Background by Saki: http://www.eastoftheweb.com/short-stories/UBooks/Bac.shtml

“The young have aspirations that never come to pass, the old have reminiscences of what never happened.”

― Saki (1870 - 1916)

Berenice by Edgar Allan Poe

Since there are a few dozen reviews already posted here, in the spirit of freshness I will compare Poe’s tale with a few other tales, each of these other tales picking up on a Berenice theme.

OBSESSION

In The Gaze by Jean Richepin, the narrator peers through the window of a cell at a madman, arms spread, head uplifted, transfixed by a point on a wall near the ceiling. The doctor-alienist relates to the narrator how this inmate is obsessed with the gaze of eyes from an artist’s portrait. “For there was something in that gaze, believe me, that could trouble not only the already-enfeebled brain of a man afflicted with general paralysis, but even a sound and solid mind.” Indeed, as it turns out, the doctor-alienist is, in his own way, obsessed with the eyes of the portrait. Obsession in this tale is clear-cut and unambiguous, the level-headed narrator encountering two different men obsessed by painterly eyes.

TEETH

Toward the end of At the Death-Bed by Guy de Maupassant, a tale told by an old man reflecting back on an experience he has years ago when he and a friend sat in a room next to the chamber where lay the corpse of German pessimistic philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. The old man relates how they both heard a sound and saw something white pass across the death bed and disappear under an armchair. Terrified, they moved to the chamber with the bed. We read, “Meanwhile my friend, who had taken the other candle, bent down. Then he touched my arm without a word. I followed his gaze and there, on the ground, under the armchair next to the bed, all white on the dark carpet, open as if ready to bite – Schopenhauer’s false teeth.” And the next sentence provides the explanation: “The rot setting in had loosened his jaws, and they has sprung from his mouth.” A horrifying experience for the old man, to be sure. But as powerful as his experience was, it had a completely rational explanation.

SPLIT IDENTITY

The Double Soul by Jean Richepin is a straightforward tale about a sixteen year-old boy who witnesses his father’s death, a witnessing that causes him, psychologically, to live as two separate persons alternately. A doctor-alienist observing the young man in his sanitarium notes, “Undoubtedly, the duplication of personality manifested itself regularly, at two-year intervals: when the two years of one personality came to an end, the other was ready to come into play; between the two of them, one curious phenomenon was indispensable, a kind of mental trigger by which the first self-yielded its place to the second.” Richepin’s tale is fascinating but the fascination emerges from a telling where the disclosing of psychological facts is direct and unmistakable.

Let’s now move to Poe’s tale, which is, in many respects, at the opposite end of the aesthetic spectrum from all three of the above. Rather than a straight-forward story told by a level-headed narrator, Poe’s tale-teller conveys how he has been sickly and morose and mentally unbalanced since childhood, which, of course, alerts us to question his reliability. And to add to the eeriness and the Gothic, the tale is told in the gloomy, gray book-lined chamber of the family mansion where the narrator was born and where his mother died. There is something suffocating and ghastly and unreal permeating the atmosphere. We read, “The realities of the world affected me as visions, and as visions only, while the wild ideas of the land of dreams became, in turn, - not the material of my every-day existence but in very deed that existence utterly and solely in itself.” In other words, for the narrator, his dream-world is his concrete reality.

Dark and creepy is ratcheted up several notches as the narrator goes on to sketch how he and his cousin Berenice grew up together – he himself cloistered indoors in ill-health, Berenice rambling outdoors in energetic radiant health. Radiant health, that is, until Berenice is stricken by a debilitating illness the narrator describes as a kind of extreme epilepsy. Meanwhile, the narrator's own disease grows, a sickness and intensity of nerves he terms monomania, where he obsesses on objects or words for hours, for days and sometimes even weeks. We read how his obsession affects his perception of his cousin: “True to its own character, my disorder reveled in the less important but more startling changes wrought in the physical frame of Berenice – in the singular and most appalling distortions of her personal identity.”

How does the narrator distort Berenice’s personal identity? Dark and creepy is ratcheted up yet again as the narrator further mixes his obsession with dream-visions of Bernice. We read, “The eyes were lifeless, and lusterless, and seemingly pupil-less, and I shrank involuntarily from their glassy stare to the contemplation of the thin and shrunken lips. They parted; and in a smile of peculiar meaning, the teeth of the changed Berenice disclosed themselves slowly to my view.” Ah, to have your lover’s teeth take on a life of their own in your obsessive, monomaniacal, twisted, morbid mind!

I wouldn’t want to continue with quotes or relaying the details of Poe’s tale so as to possibly spoil the ending for readers. It is enough to point out that Poe didn’t stop here. There is ample evidence at the end of the tale that the narrator suffers from another disorder so extreme even he cannot face it squarely – that disorder being split identity or what in medical parlance is known as dissociative identity disorder (previously known as multiple personality disorder).

Is it any wonder at the time of the tale’s publication in 1835 Poe’s critics and readers said the author went too far, that this Gothic tale was so ghastly and gruesome as to offend good taste? And I didn’t even touch on the possibility of Berenice being buried alive! Nearly two hundred years later this tale of horror can still raise the hairs on the back of a reader’s neck.

*The quotes from the two Jean Richepin stories are from Crazy Corner translated by Brian Stableford and published by Black Coat Press. The quotes from Guy de Maupassant’s tale come from French Decadent Tales, translated by Stephen Romer and published by Oxford University Press.

5.0

Since there are a few dozen reviews already posted here, in the spirit of freshness I will compare Poe’s tale with a few other tales, each of these other tales picking up on a Berenice theme.

OBSESSION

In The Gaze by Jean Richepin, the narrator peers through the window of a cell at a madman, arms spread, head uplifted, transfixed by a point on a wall near the ceiling. The doctor-alienist relates to the narrator how this inmate is obsessed with the gaze of eyes from an artist’s portrait. “For there was something in that gaze, believe me, that could trouble not only the already-enfeebled brain of a man afflicted with general paralysis, but even a sound and solid mind.” Indeed, as it turns out, the doctor-alienist is, in his own way, obsessed with the eyes of the portrait. Obsession in this tale is clear-cut and unambiguous, the level-headed narrator encountering two different men obsessed by painterly eyes.

TEETH

Toward the end of At the Death-Bed by Guy de Maupassant, a tale told by an old man reflecting back on an experience he has years ago when he and a friend sat in a room next to the chamber where lay the corpse of German pessimistic philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. The old man relates how they both heard a sound and saw something white pass across the death bed and disappear under an armchair. Terrified, they moved to the chamber with the bed. We read, “Meanwhile my friend, who had taken the other candle, bent down. Then he touched my arm without a word. I followed his gaze and there, on the ground, under the armchair next to the bed, all white on the dark carpet, open as if ready to bite – Schopenhauer’s false teeth.” And the next sentence provides the explanation: “The rot setting in had loosened his jaws, and they has sprung from his mouth.” A horrifying experience for the old man, to be sure. But as powerful as his experience was, it had a completely rational explanation.

SPLIT IDENTITY

The Double Soul by Jean Richepin is a straightforward tale about a sixteen year-old boy who witnesses his father’s death, a witnessing that causes him, psychologically, to live as two separate persons alternately. A doctor-alienist observing the young man in his sanitarium notes, “Undoubtedly, the duplication of personality manifested itself regularly, at two-year intervals: when the two years of one personality came to an end, the other was ready to come into play; between the two of them, one curious phenomenon was indispensable, a kind of mental trigger by which the first self-yielded its place to the second.” Richepin’s tale is fascinating but the fascination emerges from a telling where the disclosing of psychological facts is direct and unmistakable.

Let’s now move to Poe’s tale, which is, in many respects, at the opposite end of the aesthetic spectrum from all three of the above. Rather than a straight-forward story told by a level-headed narrator, Poe’s tale-teller conveys how he has been sickly and morose and mentally unbalanced since childhood, which, of course, alerts us to question his reliability. And to add to the eeriness and the Gothic, the tale is told in the gloomy, gray book-lined chamber of the family mansion where the narrator was born and where his mother died. There is something suffocating and ghastly and unreal permeating the atmosphere. We read, “The realities of the world affected me as visions, and as visions only, while the wild ideas of the land of dreams became, in turn, - not the material of my every-day existence but in very deed that existence utterly and solely in itself.” In other words, for the narrator, his dream-world is his concrete reality.

Dark and creepy is ratcheted up several notches as the narrator goes on to sketch how he and his cousin Berenice grew up together – he himself cloistered indoors in ill-health, Berenice rambling outdoors in energetic radiant health. Radiant health, that is, until Berenice is stricken by a debilitating illness the narrator describes as a kind of extreme epilepsy. Meanwhile, the narrator's own disease grows, a sickness and intensity of nerves he terms monomania, where he obsesses on objects or words for hours, for days and sometimes even weeks. We read how his obsession affects his perception of his cousin: “True to its own character, my disorder reveled in the less important but more startling changes wrought in the physical frame of Berenice – in the singular and most appalling distortions of her personal identity.”

How does the narrator distort Berenice’s personal identity? Dark and creepy is ratcheted up yet again as the narrator further mixes his obsession with dream-visions of Bernice. We read, “The eyes were lifeless, and lusterless, and seemingly pupil-less, and I shrank involuntarily from their glassy stare to the contemplation of the thin and shrunken lips. They parted; and in a smile of peculiar meaning, the teeth of the changed Berenice disclosed themselves slowly to my view.” Ah, to have your lover’s teeth take on a life of their own in your obsessive, monomaniacal, twisted, morbid mind!

I wouldn’t want to continue with quotes or relaying the details of Poe’s tale so as to possibly spoil the ending for readers. It is enough to point out that Poe didn’t stop here. There is ample evidence at the end of the tale that the narrator suffers from another disorder so extreme even he cannot face it squarely – that disorder being split identity or what in medical parlance is known as dissociative identity disorder (previously known as multiple personality disorder).

Is it any wonder at the time of the tale’s publication in 1835 Poe’s critics and readers said the author went too far, that this Gothic tale was so ghastly and gruesome as to offend good taste? And I didn’t even touch on the possibility of Berenice being buried alive! Nearly two hundred years later this tale of horror can still raise the hairs on the back of a reader’s neck.

*The quotes from the two Jean Richepin stories are from Crazy Corner translated by Brian Stableford and published by Black Coat Press. The quotes from Guy de Maupassant’s tale come from French Decadent Tales, translated by Stephen Romer and published by Oxford University Press.

The Man Of The Crowd by Edgar Allan Poe

Published in 1845, The Man of the Crowd by Edgar Allan Poe is a fascinating tale exploring, among other topics, the various ways we can be present in the world and experience the people and life around us.

For such nineteenth century thinkers as Arthur Schopenhauer aesthetic experience is a way to lift us above our everyday concerns, material desires and emotional sufferings to a realm of intellectual contemplation that is most pleasant and freeing. This is, in fact, the narrator’s mindset for the first half of the story when he sits in a coffeehouse in a happy mood, free of boredom, with clear-headedness and a sense of exhilaration so that “Merely to breathe was enjoyable.” He has been feeling calm and keenly interested in his cigar, his paper and the people in the coffeehouse for some time when he turns his attention to the coffeehouse window and the mass of humanity pounding the pavement outside.

Listening to his account, it’s as if he is a spectator sitting in his box at the theater, watching the play of everyday urban life where the actors are men and women from London’s social classes and cultural strata, top to bottom. The narrator categorizes and describes in colorful detail the appearance of decent business-types, haggard clerks, pick-pockets, gamblers, dandies, military men, peddlers, beggars, invalids, young girls, the elderly, drunkards, porters, coal-heavers, organ-grinders, laborers and monkey-exhibiters.

Then, when night descends and the gas-lights turn on, as if in answer to the shifting light, the narrator shifts his focus from overall physical appearances and clothing to an examination of individual faces. We read, “Although the rapidity with which the world of light flitted before the window, prevented me from casting more than a glance upon each visage, still it seemed that, in my then peculiar mental state, I could frequently read, even in that brief interval of a glance, the history of long years.”

Perhaps his "peculiar mental state" is heightened intuition from his prolonged aesthetic experience, but, whatever it is, as he looks out the coffeehouse window, the narrator thinks he can read an individual’s life history by momentarily viewing his or her face.

Then, something unexpected happens: the narrator sees an old man between sixty-five and seventy, an old man who’s face is so arresting and absorbing and idiosyncratic, the narrator feels compelled to leave his seat at the window and follow him down the street. Will he learn more about this old man with a face that prompts ideas of such things as vast mental power, of triumph, of blood-thirstiness, of excessive terror?

The narrator is certainly willing to sacrifice his calm, happy mood and enjoyable breathing to find out. We read, “I felt singularly aroused, startled, fascinated. Then came a craving desire to keep the man in view – to know more of him. Hurriedly putting on an overcoat, and seizing my hat and cane, I made my way into the street.” So, it’s bye, bye happy, relaxed contemplation; hello, craving desire and psychological fascination.

And here we follow the narrator as he experiences an entirely different way of being in the world, a totally different way to experience life and observe people. The mindset he adopts is intriguing, mainly the attitude of a private detective trailing a suspect with a tincture of flâneur, that is, an explorer and connoisseur of the street.

The narrator’s excitement and inquisitiveness is heightened; he is willing to race through London streets for hours, even the dangerous and dilapidated East End and even in the rain. Poe writes, “The rain fell fast; the air grew cold. Down this, some quarter of a mile long, he rushed with an activity I could not have dreamed of seeing in one so aged, and which put me to much trouble in pursuit.”

The narrator relays his many observations and judgments about the old man of the crowd as he follows his path for hours and hours, until the rising of the sun the next day. Now, that’s headstrong fascination! Ultimately, the narrator doesn’t like what he discovers and concludes for such as the old man of the crowd, he can learn no more.

What I personally find fascinating is Poe’s penetrating insight that our intention and focus and mindset radically alters our perception; how, when we shift from calm philosophical to aroused and desirous, we are, in a very real sense, encountering a different world. What an altered experience the narrator of this tale would have had if, after putting on his hat and coat and running from the coffeehouse, he couldn’t locate the old man. What a dissimilar world he would have seen if he reverted to his calm, aesthetic contemplation, randomly and casually strolling London’s streets.

5.0

Published in 1845, The Man of the Crowd by Edgar Allan Poe is a fascinating tale exploring, among other topics, the various ways we can be present in the world and experience the people and life around us.

For such nineteenth century thinkers as Arthur Schopenhauer aesthetic experience is a way to lift us above our everyday concerns, material desires and emotional sufferings to a realm of intellectual contemplation that is most pleasant and freeing. This is, in fact, the narrator’s mindset for the first half of the story when he sits in a coffeehouse in a happy mood, free of boredom, with clear-headedness and a sense of exhilaration so that “Merely to breathe was enjoyable.” He has been feeling calm and keenly interested in his cigar, his paper and the people in the coffeehouse for some time when he turns his attention to the coffeehouse window and the mass of humanity pounding the pavement outside.

Listening to his account, it’s as if he is a spectator sitting in his box at the theater, watching the play of everyday urban life where the actors are men and women from London’s social classes and cultural strata, top to bottom. The narrator categorizes and describes in colorful detail the appearance of decent business-types, haggard clerks, pick-pockets, gamblers, dandies, military men, peddlers, beggars, invalids, young girls, the elderly, drunkards, porters, coal-heavers, organ-grinders, laborers and monkey-exhibiters.

Then, when night descends and the gas-lights turn on, as if in answer to the shifting light, the narrator shifts his focus from overall physical appearances and clothing to an examination of individual faces. We read, “Although the rapidity with which the world of light flitted before the window, prevented me from casting more than a glance upon each visage, still it seemed that, in my then peculiar mental state, I could frequently read, even in that brief interval of a glance, the history of long years.”

Perhaps his "peculiar mental state" is heightened intuition from his prolonged aesthetic experience, but, whatever it is, as he looks out the coffeehouse window, the narrator thinks he can read an individual’s life history by momentarily viewing his or her face.

Then, something unexpected happens: the narrator sees an old man between sixty-five and seventy, an old man who’s face is so arresting and absorbing and idiosyncratic, the narrator feels compelled to leave his seat at the window and follow him down the street. Will he learn more about this old man with a face that prompts ideas of such things as vast mental power, of triumph, of blood-thirstiness, of excessive terror?

The narrator is certainly willing to sacrifice his calm, happy mood and enjoyable breathing to find out. We read, “I felt singularly aroused, startled, fascinated. Then came a craving desire to keep the man in view – to know more of him. Hurriedly putting on an overcoat, and seizing my hat and cane, I made my way into the street.” So, it’s bye, bye happy, relaxed contemplation; hello, craving desire and psychological fascination.

And here we follow the narrator as he experiences an entirely different way of being in the world, a totally different way to experience life and observe people. The mindset he adopts is intriguing, mainly the attitude of a private detective trailing a suspect with a tincture of flâneur, that is, an explorer and connoisseur of the street.

The narrator’s excitement and inquisitiveness is heightened; he is willing to race through London streets for hours, even the dangerous and dilapidated East End and even in the rain. Poe writes, “The rain fell fast; the air grew cold. Down this, some quarter of a mile long, he rushed with an activity I could not have dreamed of seeing in one so aged, and which put me to much trouble in pursuit.”

The narrator relays his many observations and judgments about the old man of the crowd as he follows his path for hours and hours, until the rising of the sun the next day. Now, that’s headstrong fascination! Ultimately, the narrator doesn’t like what he discovers and concludes for such as the old man of the crowd, he can learn no more.

What I personally find fascinating is Poe’s penetrating insight that our intention and focus and mindset radically alters our perception; how, when we shift from calm philosophical to aroused and desirous, we are, in a very real sense, encountering a different world. What an altered experience the narrator of this tale would have had if, after putting on his hat and coat and running from the coffeehouse, he couldn’t locate the old man. What a dissimilar world he would have seen if he reverted to his calm, aesthetic contemplation, randomly and casually strolling London’s streets.

How to Defend Yourself Against Scorpions by Fernando Sorrentino

Over two dozen finely crafted absurdist short stories from Argentina’s Fernando Sorrentino. In its pages we encounter the city of Buenos Aries overrun with scorpions, a wart on a man's pinky finger grows into an elephant, cockroaches dream of becoming rhinos, alligators dance with tourists, parakeets threaten to take over the world and an old man exhibits the dark, creepy qualities of a vampire. To provide a more specific taste of this outstanding author's work, below is my write-up of two stories from the collection I found particularly fascinating:

ENGINEER SISMONDI'S NOTEBOOK

Engineer Sismondi travels to República Autónoma deep in the Brazilian jungle. From all those pictures he saw in magazines, the little city struck him as an anthology of extravagances and anachronisms. For one thing, the city was built in the shape of a hexagon, surrounded by high walls like a medieval town with its five streets following the same hexagonal pattern of the outer walls all the way to the park at the city's center. And the avenues, four in number, run from north, south, east and west, from outer walls to the center. No question, Sismondi muses, this peculiar specimen of modern geometrical architecture might just have been built to attract North American and Japanese tourists.

Upon entering the jungle city and making his obligatory visit to the admissions office, Sismondi quickly discovers as well-ordered and impeccable as the surrounding glass, steel and acrylics within the air-conditioned building, the trim, thirty-something women with their blue eyes, pulled back blonde hair and pale smooth skin, women who all seemed to resemble each other, speak to him in a mocking, condescending tone. Added to this, some of their questions and statements are downright insulting. Our twenty-seven-year-old engineer is beginning to feel more than a tad uncomfortable.

Once outside on the street, studying a map of the city, Sismondi detects the design is as artificial as it is simple, constructed as if in defiance of the naturalness of the surrounding jungle. The visiting engineer is made even more nervous and anxious when the bell boy at his hotel rejects his tip angrily, glaring at him with hateful eyes and then slams the door on his way out.

But the real drama begins when engineer Sismondi records in his notebook how one evening while dinning at a restaurant, his passion is aroused by the sight of a lovely young curvaceous woman, probably Argentinian of Arab ancestry, with large black eyes and dark curly hair. But she is with another man. Darn! Several days later, while drinking coffee at an outdoor café, this same beauty drops a note on the sidewalk next to him. Returning to his hotel room, he reads her name is Isabel Simes and she is being accused of a crime she didn’t commit that carries the death penalty. Isabel asks him to contact her father at a specific address in Rio de Janeiro.

Sismondi acts but he is then immediately summoned to the city’s police headquarters. What follows will remind a reader of Franz Kafka, such tales as Before the Law, The Trial and The Castle. However, this is not Kafka, this is Fernando Sorrentino - thus we have a Kafkaesque nightmare with an absurdist curveball thrown in at the very end. Thank you, Fernando. An unforgettable literary lollapalooza.

A LIFE PERHAPS WORTH RESTORING

Mister Sanitation: Our unnamed narrator tells us right off he is obsessive about cleanliness – he doesn’t touch dogs or cats and does everything in his power to rid his home of spiders and insects. He also takes the necessary, vital steps to avoid being in close range of a mosquito or fly. Rotten potato in his very apartment - alarming; a mouse, or, even a worse, horror of horrors, a rat – unthinkable. At a comfortable distance we as readers and observers might laugh at someone with such an obsession but actually living with this affliction is no laughing matter. The medical profession considers obsessive-compulsive a disorder, and for good reason.

Malignant Rodent: Very grievous news – Mr. Sanitation detects there is a malevolent presence in the form of a mouse in his apartment. But, where? The mouse hunt is on - as if that nasty rodent were the bearer of plague-carrying fleas, every square inch of kitchen, bathroom, dining room and bedroom undergo diligent, rigorous, microscopic inspection. The results? Even with high power objective lens turned to its highest power of magnification, no mouse.

Sterilized and Sanitized: To make sure we know just how completely and thoroughly he is committed to minimizing possible contamination and maximizing the antiseptic, our narrator enumerates his habits of eating and living, as when he uses boiling water and detergent to scrub clean his plate, glass, fork and knife. Of course, feeling the need to convey such details as part of his story underscores how easily obsession can overwhelm.

Rats!: Our narrator is no longer bound to office work or teaching school, jobs he found uncomfortable for reasons pertaining to culture, economics and ethics “in that strict order” (you have to love how, true to form as an obsessive-compulsive, he makes sure we know the strict order). So, what does our Mr. Sanitation do for a living? Since he enjoys reading, has a keen ability in foreign languages and cherishes his independence, he now has his dream job: sitting alone in his antiseptic apartment, performing the work of a translator, mostly for large American publishers. And, a live-in partner or wife? No way, José - no need and the disruption to his fanatically neat and polished living space would be highly distasteful. But to suffer the intrusion of a rat! Yes, at this point that rodent is not a mouse but a rat.

Seeking Help: He pays a visit to his local veterinary clinic to inquire on the most effective method for ridding his apartment of rats. The interchange with the woman behind the desk is laugh-out-loud hilarious. When he is about ready to walk out the door, rat pills in hand, we read: “Although I would have preferred a less grotesque and scientific, less Anglo-Saxon plan, something a bit more trustful like facing the rat and trying to kill it by hitting it on the head with a shovel, for instance, I accepted her satanic prescription because truly, I no longer had the strength or the will to start a face to face confrontation.”

The Crackup: Events turn weird for Mr. Sanitation beginning that very night when he is woken from a sound sleep and thinks he hears the rat tap-tap-tapping. Ah, echoes of Edgar Allen Poe, perhaps? His calm, methodical strategy is forever abandoned; our narrator declares henceforth he will take on the role of an irrational fighter. I wouldn’t want to spoil the story for a reader so I’ll end by mentioning he makes a startling discovery the next morning which prompts him to revisit that veterinary clinic where he walks out with much more than simply rat poison.

5.0

Over two dozen finely crafted absurdist short stories from Argentina’s Fernando Sorrentino. In its pages we encounter the city of Buenos Aries overrun with scorpions, a wart on a man's pinky finger grows into an elephant, cockroaches dream of becoming rhinos, alligators dance with tourists, parakeets threaten to take over the world and an old man exhibits the dark, creepy qualities of a vampire. To provide a more specific taste of this outstanding author's work, below is my write-up of two stories from the collection I found particularly fascinating:

ENGINEER SISMONDI'S NOTEBOOK

Engineer Sismondi travels to República Autónoma deep in the Brazilian jungle. From all those pictures he saw in magazines, the little city struck him as an anthology of extravagances and anachronisms. For one thing, the city was built in the shape of a hexagon, surrounded by high walls like a medieval town with its five streets following the same hexagonal pattern of the outer walls all the way to the park at the city's center. And the avenues, four in number, run from north, south, east and west, from outer walls to the center. No question, Sismondi muses, this peculiar specimen of modern geometrical architecture might just have been built to attract North American and Japanese tourists.

Upon entering the jungle city and making his obligatory visit to the admissions office, Sismondi quickly discovers as well-ordered and impeccable as the surrounding glass, steel and acrylics within the air-conditioned building, the trim, thirty-something women with their blue eyes, pulled back blonde hair and pale smooth skin, women who all seemed to resemble each other, speak to him in a mocking, condescending tone. Added to this, some of their questions and statements are downright insulting. Our twenty-seven-year-old engineer is beginning to feel more than a tad uncomfortable.

Once outside on the street, studying a map of the city, Sismondi detects the design is as artificial as it is simple, constructed as if in defiance of the naturalness of the surrounding jungle. The visiting engineer is made even more nervous and anxious when the bell boy at his hotel rejects his tip angrily, glaring at him with hateful eyes and then slams the door on his way out.

But the real drama begins when engineer Sismondi records in his notebook how one evening while dinning at a restaurant, his passion is aroused by the sight of a lovely young curvaceous woman, probably Argentinian of Arab ancestry, with large black eyes and dark curly hair. But she is with another man. Darn! Several days later, while drinking coffee at an outdoor café, this same beauty drops a note on the sidewalk next to him. Returning to his hotel room, he reads her name is Isabel Simes and she is being accused of a crime she didn’t commit that carries the death penalty. Isabel asks him to contact her father at a specific address in Rio de Janeiro.

Sismondi acts but he is then immediately summoned to the city’s police headquarters. What follows will remind a reader of Franz Kafka, such tales as Before the Law, The Trial and The Castle. However, this is not Kafka, this is Fernando Sorrentino - thus we have a Kafkaesque nightmare with an absurdist curveball thrown in at the very end. Thank you, Fernando. An unforgettable literary lollapalooza.

A LIFE PERHAPS WORTH RESTORING

Mister Sanitation: Our unnamed narrator tells us right off he is obsessive about cleanliness – he doesn’t touch dogs or cats and does everything in his power to rid his home of spiders and insects. He also takes the necessary, vital steps to avoid being in close range of a mosquito or fly. Rotten potato in his very apartment - alarming; a mouse, or, even a worse, horror of horrors, a rat – unthinkable. At a comfortable distance we as readers and observers might laugh at someone with such an obsession but actually living with this affliction is no laughing matter. The medical profession considers obsessive-compulsive a disorder, and for good reason.

Malignant Rodent: Very grievous news – Mr. Sanitation detects there is a malevolent presence in the form of a mouse in his apartment. But, where? The mouse hunt is on - as if that nasty rodent were the bearer of plague-carrying fleas, every square inch of kitchen, bathroom, dining room and bedroom undergo diligent, rigorous, microscopic inspection. The results? Even with high power objective lens turned to its highest power of magnification, no mouse.

Sterilized and Sanitized: To make sure we know just how completely and thoroughly he is committed to minimizing possible contamination and maximizing the antiseptic, our narrator enumerates his habits of eating and living, as when he uses boiling water and detergent to scrub clean his plate, glass, fork and knife. Of course, feeling the need to convey such details as part of his story underscores how easily obsession can overwhelm.

Rats!: Our narrator is no longer bound to office work or teaching school, jobs he found uncomfortable for reasons pertaining to culture, economics and ethics “in that strict order” (you have to love how, true to form as an obsessive-compulsive, he makes sure we know the strict order). So, what does our Mr. Sanitation do for a living? Since he enjoys reading, has a keen ability in foreign languages and cherishes his independence, he now has his dream job: sitting alone in his antiseptic apartment, performing the work of a translator, mostly for large American publishers. And, a live-in partner or wife? No way, José - no need and the disruption to his fanatically neat and polished living space would be highly distasteful. But to suffer the intrusion of a rat! Yes, at this point that rodent is not a mouse but a rat.

Seeking Help: He pays a visit to his local veterinary clinic to inquire on the most effective method for ridding his apartment of rats. The interchange with the woman behind the desk is laugh-out-loud hilarious. When he is about ready to walk out the door, rat pills in hand, we read: “Although I would have preferred a less grotesque and scientific, less Anglo-Saxon plan, something a bit more trustful like facing the rat and trying to kill it by hitting it on the head with a shovel, for instance, I accepted her satanic prescription because truly, I no longer had the strength or the will to start a face to face confrontation.”

The Crackup: Events turn weird for Mr. Sanitation beginning that very night when he is woken from a sound sleep and thinks he hears the rat tap-tap-tapping. Ah, echoes of Edgar Allen Poe, perhaps? His calm, methodical strategy is forever abandoned; our narrator declares henceforth he will take on the role of an irrational fighter. I wouldn’t want to spoil the story for a reader so I’ll end by mentioning he makes a startling discovery the next morning which prompts him to revisit that veterinary clinic where he walks out with much more than simply rat poison.

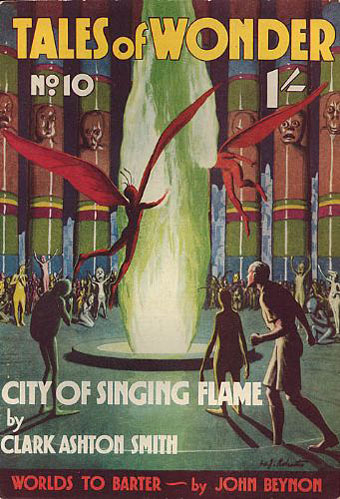

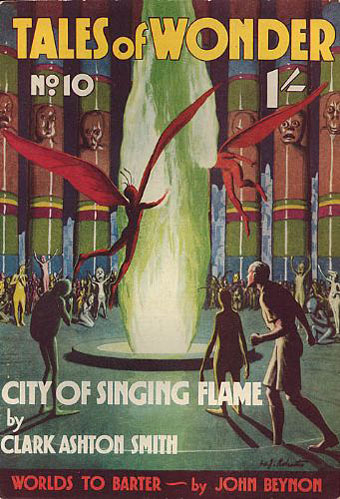

The City of the Singing Flame by Clark Ashton Smith

"And the music? I have utterly failed to describe that, also. It was as if some marvelous elixir had been turned into sound-waves — an elixir conferring the gift of superhuman life, and the high, magnificent dreams which are dreamt by the Immortals."

Clark Ashton Smith along with H.P. Lovecraft were the leading contributors to Weird Tales back in the 1920s and 1930s, the heyday of the pulp magazine, a time when the literary world past harsh judgement on authors writing in the genres of fantasy, horror or science fiction. Nowadays most critics and reviewers recognizes the mature work of these two authors are among the finest in American literature. The focus of my review will be on one such story, the title story from this Clark Ashton Smith collection, The City of the Singing Flame, a piece of deep philosophical significance.

A brief synopsis: Giles Angarth, himself an author of fantastic fiction, relates in his diary how he discovered two craters out in the Nevada desert wherein he could step between these craters and be propelled into another non-earthly dimension. This new incredible landscape leads to a city. We read:

“I was standing in the midst of a landscape which bore no degree or manner of resemblance to Crater Ridge. A long, gradual slope, covered with violet grass and studded at intervals with stones of monolithic size and shape, ran undulantly away beneath me to a broad plain with sinuous, open meadows and high, stately forests of an unknown vegetation whose predominant hues were purple and yellow. The plain seemed to end in a wall of impenetrable, golden-brownish mist, that rose with phantom pinnacles to dissolve on a sky of luminescent amber in which there was no sun.

In the foreground of this amazing scene, not more than two or three miles away, there loomed a city whose massive towers and mountainous ramparts of red stone were such as the Anakim of undiscovered worlds might build. Wall on beetling wall, spire on giant spire, it soared to confront the heavens, maintaining everywhere the severe and solemn lines of a rectilinear architecture. It seemed to overwhelm and crush down the beholder with its stern and crag-like imminence.”

Rather than saying anything further regarding the story’s many other details, I’ll turn to the alluring, mystical singing flame at the very center of both the city and the tale, a tall flame producing ecstatic sound that forcefully brings to mind the following:

Odysseus and the Sirens

In Homer’s famous epic, Odysseus had himself bound to the ship’s mast so he could hear the beautiful music of the Sirens and live to tell the tale. Giles Angarth likens the singing flame to Homer’s Sirens. But is this an accurate assessment? Is Giles judging the flame in a rather limited way, projecting his own cultural categories and prejudices? In other words, does surrendering one’s physical body to merge with the singing flame necessarily result in death? Perhaps another interpretation could be all those non-earthy creatures who leap or fly into the fame surrender personality and personhood in order to unite individual consciousness with the highest cosmic vibration, the most ecstatic, consciousness-expanding sound.

Nada Yoga

Within the world of yoga from India, there is what is known as nada yoga, the yoga of sound. Men and women following the path of yoga chant the sacred sound of OM and other seed syllables and mantras to raise their consciousness to the divine. Also, there is the path of bhakti yoga, the yoga of devotion, where music is key – kirtan, the singing of the many names of the divine. (Personal note: in years past I played mridanga drum for kirtans).

An ancient Indian mandala depicting the vibrational form that mystical seers and yogis visualized during meditation while chanting the seed sound OM.

Ambient Music

Much in the same spirit as nada yoga, modern composers such as Steve Roach and Steve Reich have employed electronics to create music associated with meditation, harmony, peace and states of bliss. Link to a sample: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uf4mZ2chDXU

Heavenly Music

Within the tradition of Christianity, celestial music has historically been linked with heaven and life eternal as with the playing of musical instruments by angels as in Hans Memling’s gorgeous fifteenth century medieval painting.

Scriabin's Music and Light Show

Lastly, to my mind, no music captures the spirit of rapture, joy and ecstasy more than Russian composer Alexander Scriabin’s 1910 Prometheus: Poem of Fire, especially the concluding sustained chord, complete with light that is meant to flood the eye. Please take a look at this astonishing performance. Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3B7uQ5K0IU

Link to Clark Ashton Smith's City of the Singing Flame: http://www.eldritchdark.com/writings/short-stories/26/the-city-of-the-singing-flame

Clark Ashton Smith - (1893-1961) - Self-educated American author who lived most of his life by himself in the log cabin in Northern California built by his parents.

5.0

"And the music? I have utterly failed to describe that, also. It was as if some marvelous elixir had been turned into sound-waves — an elixir conferring the gift of superhuman life, and the high, magnificent dreams which are dreamt by the Immortals."

Clark Ashton Smith along with H.P. Lovecraft were the leading contributors to Weird Tales back in the 1920s and 1930s, the heyday of the pulp magazine, a time when the literary world past harsh judgement on authors writing in the genres of fantasy, horror or science fiction. Nowadays most critics and reviewers recognizes the mature work of these two authors are among the finest in American literature. The focus of my review will be on one such story, the title story from this Clark Ashton Smith collection, The City of the Singing Flame, a piece of deep philosophical significance.

A brief synopsis: Giles Angarth, himself an author of fantastic fiction, relates in his diary how he discovered two craters out in the Nevada desert wherein he could step between these craters and be propelled into another non-earthly dimension. This new incredible landscape leads to a city. We read:

“I was standing in the midst of a landscape which bore no degree or manner of resemblance to Crater Ridge. A long, gradual slope, covered with violet grass and studded at intervals with stones of monolithic size and shape, ran undulantly away beneath me to a broad plain with sinuous, open meadows and high, stately forests of an unknown vegetation whose predominant hues were purple and yellow. The plain seemed to end in a wall of impenetrable, golden-brownish mist, that rose with phantom pinnacles to dissolve on a sky of luminescent amber in which there was no sun.

In the foreground of this amazing scene, not more than two or three miles away, there loomed a city whose massive towers and mountainous ramparts of red stone were such as the Anakim of undiscovered worlds might build. Wall on beetling wall, spire on giant spire, it soared to confront the heavens, maintaining everywhere the severe and solemn lines of a rectilinear architecture. It seemed to overwhelm and crush down the beholder with its stern and crag-like imminence.”

Rather than saying anything further regarding the story’s many other details, I’ll turn to the alluring, mystical singing flame at the very center of both the city and the tale, a tall flame producing ecstatic sound that forcefully brings to mind the following:

Odysseus and the Sirens

In Homer’s famous epic, Odysseus had himself bound to the ship’s mast so he could hear the beautiful music of the Sirens and live to tell the tale. Giles Angarth likens the singing flame to Homer’s Sirens. But is this an accurate assessment? Is Giles judging the flame in a rather limited way, projecting his own cultural categories and prejudices? In other words, does surrendering one’s physical body to merge with the singing flame necessarily result in death? Perhaps another interpretation could be all those non-earthy creatures who leap or fly into the fame surrender personality and personhood in order to unite individual consciousness with the highest cosmic vibration, the most ecstatic, consciousness-expanding sound.

Nada Yoga

Within the world of yoga from India, there is what is known as nada yoga, the yoga of sound. Men and women following the path of yoga chant the sacred sound of OM and other seed syllables and mantras to raise their consciousness to the divine. Also, there is the path of bhakti yoga, the yoga of devotion, where music is key – kirtan, the singing of the many names of the divine. (Personal note: in years past I played mridanga drum for kirtans).

An ancient Indian mandala depicting the vibrational form that mystical seers and yogis visualized during meditation while chanting the seed sound OM.

Ambient Music

Much in the same spirit as nada yoga, modern composers such as Steve Roach and Steve Reich have employed electronics to create music associated with meditation, harmony, peace and states of bliss. Link to a sample: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uf4mZ2chDXU

Heavenly Music

Within the tradition of Christianity, celestial music has historically been linked with heaven and life eternal as with the playing of musical instruments by angels as in Hans Memling’s gorgeous fifteenth century medieval painting.

Scriabin's Music and Light Show

Lastly, to my mind, no music captures the spirit of rapture, joy and ecstasy more than Russian composer Alexander Scriabin’s 1910 Prometheus: Poem of Fire, especially the concluding sustained chord, complete with light that is meant to flood the eye. Please take a look at this astonishing performance. Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3B7uQ5K0IU

Link to Clark Ashton Smith's City of the Singing Flame: http://www.eldritchdark.com/writings/short-stories/26/the-city-of-the-singing-flame

Clark Ashton Smith - (1893-1961) - Self-educated American author who lived most of his life by himself in the log cabin in Northern California built by his parents.

Silence: A Fable by Edgar Allan Poe

Is it any wonder fans of Edgar Allan Poe find Silence – A Fable one of the least accessible and enjoyable of his tales? This is quite understandable since this two pager lacks the development and pacing of a conventionally constructed short-story and also lacks grounding in our predictable, realistic everyday reality. Rather, what we find here is a tale having much in common with lyrical prose poetry and what in the twentieth century would become known as surrealist writing. With this very subjective world-creation of Poe’s in mind, below are several of my very subjective observations.

It’s sundown and Poe looks out at a peaceful summer landscape: river, meadow and willow trees under the setting sun, but his imagination immediately plays games, enlarging the river, distorting the meadow, altering, warping and bending the willow trees - a complete transformation right before his very eyes. Poe recognizes what is happening - it is his poetic muse taking over. But such a muse! He views the bizarre deformation and has a name for such a muse - the Demon.

With this psychological transformation in mind, the first ninety percent of this tale is told by a Demon, a telling of what the Demon sees in and around a river. And what a seeing! Below are several quotes coupled with my comments:

“For many miles on either side of the river’s oozy bed is a pale desert of gigantic water-lilies. They sigh one unto the other in that solitude, and stretch toward the heaven their long ghastly necks, and nod to and fro their everlasting heads.” Goodness! What a twisted vision: nodding water lilies with long ghastly necks. Such a vision anticipates the metamorphosing landscapes of Max Ernst.

But then there is more strangeness as the Demon scans the landscape where he sees a rock under a crimson moon. We read, “And I was going back into the morass, when the moon shone with a fuller red, and I turned and looked again upon the rock, and upon the characters were DESOLATION.”

Since Poe is a writer and not a painter, Poe’s Demon sees something Max Ernst never painted: an actual word in the landscape. Such a word in such a landscape provides a clear picture of the link between Poe’s visions and Poe’s language. Sidebar: Letters magically appearing on a rock reminds me of Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse where one lonely evening main character Harry Haller sees words magically appear on a stone wall above an ancient wooden door in an old section of a city.

Then the Demon sees a man. We are given a detailed description of the man, including the following: “And his brow was lofty with thought, and his eye wild with care; and, in a few furrows upon his cheek I read the fables of sorrow, and weariness, and disgust with mankind, and a longing for solitude.” I’m sure I am not the first reader to observe how this could be a description of Poe himself. So, in a way, this wordless interplay between Demon and man could be interpreted as the interplay between demonic muse and author.

In the last paragraph the narrator tells us what happens at the conclusion of the Demon’s story. We read, “And as the Demon made an end of his story, he fell back within the cavity of the tomb and laughed. And I could not laugh with the Demon, and he cursed me because I could not laugh.”

Perhaps this is true to form for Edgar Allan Poe - unlike many other writers and poets who can stand back and laugh at themselves, laugh and not take their writing or their life all that seriously, Poe was not such a writer. Judging from his photograph, Poe doesn’t look like a man who had many a belly-laugh in his brief life; quite the contrary, Poe looks like the prototypical angst-ridden tortured romantic poet, a man who could serve as a model for many of his tales of the macabre, a man who saw his poetic muse in the form of a Demon.

One final reflection on the phenomenon of silence – Composer/Experimental musician Joe Cage experienced a totally silent chamber but in that silent room he heard two sounds: one high, his nervous system and one low, his blood circulating. Perhaps Poe was being ironic with his title Silence – A Fable, since, in our very human experience of the world, silence is, in fact, a fable. There is always sound.

5.0

Is it any wonder fans of Edgar Allan Poe find Silence – A Fable one of the least accessible and enjoyable of his tales? This is quite understandable since this two pager lacks the development and pacing of a conventionally constructed short-story and also lacks grounding in our predictable, realistic everyday reality. Rather, what we find here is a tale having much in common with lyrical prose poetry and what in the twentieth century would become known as surrealist writing. With this very subjective world-creation of Poe’s in mind, below are several of my very subjective observations.

It’s sundown and Poe looks out at a peaceful summer landscape: river, meadow and willow trees under the setting sun, but his imagination immediately plays games, enlarging the river, distorting the meadow, altering, warping and bending the willow trees - a complete transformation right before his very eyes. Poe recognizes what is happening - it is his poetic muse taking over. But such a muse! He views the bizarre deformation and has a name for such a muse - the Demon.

With this psychological transformation in mind, the first ninety percent of this tale is told by a Demon, a telling of what the Demon sees in and around a river. And what a seeing! Below are several quotes coupled with my comments:

“For many miles on either side of the river’s oozy bed is a pale desert of gigantic water-lilies. They sigh one unto the other in that solitude, and stretch toward the heaven their long ghastly necks, and nod to and fro their everlasting heads.” Goodness! What a twisted vision: nodding water lilies with long ghastly necks. Such a vision anticipates the metamorphosing landscapes of Max Ernst.

But then there is more strangeness as the Demon scans the landscape where he sees a rock under a crimson moon. We read, “And I was going back into the morass, when the moon shone with a fuller red, and I turned and looked again upon the rock, and upon the characters were DESOLATION.”

Since Poe is a writer and not a painter, Poe’s Demon sees something Max Ernst never painted: an actual word in the landscape. Such a word in such a landscape provides a clear picture of the link between Poe’s visions and Poe’s language. Sidebar: Letters magically appearing on a rock reminds me of Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse where one lonely evening main character Harry Haller sees words magically appear on a stone wall above an ancient wooden door in an old section of a city.

Then the Demon sees a man. We are given a detailed description of the man, including the following: “And his brow was lofty with thought, and his eye wild with care; and, in a few furrows upon his cheek I read the fables of sorrow, and weariness, and disgust with mankind, and a longing for solitude.” I’m sure I am not the first reader to observe how this could be a description of Poe himself. So, in a way, this wordless interplay between Demon and man could be interpreted as the interplay between demonic muse and author.

In the last paragraph the narrator tells us what happens at the conclusion of the Demon’s story. We read, “And as the Demon made an end of his story, he fell back within the cavity of the tomb and laughed. And I could not laugh with the Demon, and he cursed me because I could not laugh.”

Perhaps this is true to form for Edgar Allan Poe - unlike many other writers and poets who can stand back and laugh at themselves, laugh and not take their writing or their life all that seriously, Poe was not such a writer. Judging from his photograph, Poe doesn’t look like a man who had many a belly-laugh in his brief life; quite the contrary, Poe looks like the prototypical angst-ridden tortured romantic poet, a man who could serve as a model for many of his tales of the macabre, a man who saw his poetic muse in the form of a Demon.

One final reflection on the phenomenon of silence – Composer/Experimental musician Joe Cage experienced a totally silent chamber but in that silent room he heard two sounds: one high, his nervous system and one low, his blood circulating. Perhaps Poe was being ironic with his title Silence – A Fable, since, in our very human experience of the world, silence is, in fact, a fable. There is always sound.

Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace by Nikil Saval

One of the dirty little secrets of the modern world is how many people's waking hours can be reduced to sitting behind a desk in an office, hour after hour, day after day, year after year, droning away, performing tasks either tasteless or downright repugnant.

This little book about modern office cubes is most insightful. Having had the nasty experience of being chained to a desk myself as a young man, I offer the following warning in the form of a micro-fiction:

OVERTIME

For many years Neal Merman commuted back and forth to his place of work like the others. It was to an insurance office, a room with blank walls, linoleum floor and forty desks under naked florescent lights. Coming in with regularity, Neal performed the job of an everyday clerk.

This mechanical routine shifted abruptly, however, when Neal became part of his desk. First, the desk absorbed only two fingers, but by the end of that afternoon, his entire left hand was sucked up by the metal. And the following morning Neal’s left leg from the knee down also became part of his desk. So it continued for a week until the only Neal to be seen was a right arm positioned beside a head and neck on the desk top.

When the other clerks arrived in the morning, all of them could see what was left of Neal, head down and pencil in hand, reviewing a file with utmost care. To aid his review, Neal would punch figures into his calculator fluently and with the dexterity of someone who knows he is total command of his skill. Such acumen brought a wry smile to Neal’s face.

One day, Big Bart, the department boss, came by to check on Neal’s files. “Your work, clerk, is better and better, although you are now more desk than flesh and bones.”

“What files do you want me to review today?” Neal asked, still scrutinizing some figures.

“Not too many files, clerk, but enough to keep you.” Big Bart withdrew and Neal followed him with his eyes until his boss could no longer be seen.

Later that same day Neal’s right arm faded into the metal. Then, like a periscope being lowered from the surface of the sea, his neck, jaw and nose sank down, leaving his eyes slightly above the gray slab. Neal looked forward and saw his pencil straight on – a long gleaming yellow cylinder with shiny eraser band at the end. Over the pencil, his telephone swelled like some giant mountain. Hearing the phone ring, Neal instinctively reached for the receiver, but this was only a mental gesture. Neal felt his forehead sinking and closed his eyes.

5.0

One of the dirty little secrets of the modern world is how many people's waking hours can be reduced to sitting behind a desk in an office, hour after hour, day after day, year after year, droning away, performing tasks either tasteless or downright repugnant.

This little book about modern office cubes is most insightful. Having had the nasty experience of being chained to a desk myself as a young man, I offer the following warning in the form of a micro-fiction:

OVERTIME

For many years Neal Merman commuted back and forth to his place of work like the others. It was to an insurance office, a room with blank walls, linoleum floor and forty desks under naked florescent lights. Coming in with regularity, Neal performed the job of an everyday clerk.

This mechanical routine shifted abruptly, however, when Neal became part of his desk. First, the desk absorbed only two fingers, but by the end of that afternoon, his entire left hand was sucked up by the metal. And the following morning Neal’s left leg from the knee down also became part of his desk. So it continued for a week until the only Neal to be seen was a right arm positioned beside a head and neck on the desk top.

When the other clerks arrived in the morning, all of them could see what was left of Neal, head down and pencil in hand, reviewing a file with utmost care. To aid his review, Neal would punch figures into his calculator fluently and with the dexterity of someone who knows he is total command of his skill. Such acumen brought a wry smile to Neal’s face.

One day, Big Bart, the department boss, came by to check on Neal’s files. “Your work, clerk, is better and better, although you are now more desk than flesh and bones.”

“What files do you want me to review today?” Neal asked, still scrutinizing some figures.

“Not too many files, clerk, but enough to keep you.” Big Bart withdrew and Neal followed him with his eyes until his boss could no longer be seen.

Later that same day Neal’s right arm faded into the metal. Then, like a periscope being lowered from the surface of the sea, his neck, jaw and nose sank down, leaving his eyes slightly above the gray slab. Neal looked forward and saw his pencil straight on – a long gleaming yellow cylinder with shiny eraser band at the end. Over the pencil, his telephone swelled like some giant mountain. Hearing the phone ring, Neal instinctively reached for the receiver, but this was only a mental gesture. Neal felt his forehead sinking and closed his eyes.

Unjustified Fears by Fernando Sorrentino

Over the span of our human evolution we have developed a powerful capacity and instinct for fear – a faculty not only good but vitally necessary when we consider all those millions of years when we were the prey of leopards, tigers and other predators hunting us in the dark at night.

However, in our modern world, many the time when our fear can work against us, not only causing great physical as well as psychological harm, but, if unchecked, can take over, crippling and debilitating us, reducing our life to a shaking, terrified bundle of raw nerves. Thus, I have always found great wisdom in the words of Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev: “Fear is never a good counselor and victory over fear is the first spiritual duty of man.”

I recall my own boyhood fear. My bedroom was a converted attic, a long, narrow dimly-lit room with a ceiling slanting at odd angles. Every night became an adventure in dealing with my overly active imagination. And all those many horror films repeated again and again on television certainly didn’t help. This went on for years but eventually as a young adult, through the practice of meditation, I overcame my fear of the dark.

Perhaps my own wrestling with fear made me particularly attuned to understanding what others might be going through when held in the grip of their own fear. Whatever else you might say or think, one thing for sure – being incapacitated and debilitated by fear is no fun. If we ask: how far can fear incapacitate, debilitate or cripple? No better answer to this question than absurdist fiction writer Fernando Sorrentino's following story.

Poor Enrique Viani! Not only is Enrique literary held in check by his fear of a spider but his mindset is so rigid, his fear so intense, that even when the spider is no longer present, he is incapable of change since his entire identity has become entwined with the defense he has constructed. One of the more insightful tales I’ve come across. Here it is:

UNJUSTIFIED FEARS

I'm not very sociable, and often I forget about my friends. After letting two years go by, on one of those January days in 1979 - they're so hot - I went to visit a friend who suffers from somewhat unjustified fears. His name doesn't matter; let's call him - just call him - Enrique Viani.

On a certain Saturday in March, 1977, his life changed course.

It seems that, while in the living room of his house, near the door to the balcony, Enrique Viani saw, suddenly, an "enor-mous" - according to him - spider on his right shoe. No sooner had he had the thought this was the biggest spider he'd seen in his life, when, suddenly leaving its place on his shoe, the animal slipped up his pants leg between the leg and the pants.

Enrique Viani was - he said - "petrified." Nothing so disagreeable had ever happened to him. At that instant he recalled two principles he had read somewhere or other, which were: 1) that, without exception, all spiders, even the smallest ones, carry poison, and can inject it; and, 2) that spiders only sting when they feel attacked or disturbed. It was plain to see, that huge spider must surely have plenty of poison in it, the full strength toxic type. So, Enrique Viani thought the most sensible thing to do was hold stock still, since at the least move of his, the insect would inject him with a definitive dose of deadly poison.

So he kept rigid for five or six hours, with the reasonable hope that the spider would eventually leave the spot it had taken up on his right tibia; clearly, it couldn't stay too long in a place where it couldn't find any food.

As he came up with this optimistic prediction, he felt that, indeed, the visitor was starting to move. It was such a bulky, heavy spider that Enrique Viani could feel - and count - the footfalls of the eight feet - hairy and slightly sticky - across the goose flesh of his leg. But, unfortunately, the guest was not leaving; instead, it nested, with its warm and throbbing cephalothorax and abdomen, in the hollow we all have behind our knees.

Up to here we have the first - and, of course, fundamental - part of this story. After that there came some not very significant variations: the basic fact was that Enrique Viani, afraid of getting stung, insisted on keeping stone still as long as need be, despite his wife and two daughters' pleas for him to abandon the plan. And so, they came to a stalemate where no progress was possible.

Then Graciela - the wife - did me the honor of calling me in to see if I could resolve the problem. This happened around two in the afternoon: I was a bit annoyed to have to give up my one siesta of the week and I silently cursed out people who can't manage their own affairs. Once over at Enrique Viani's house, I found a pathetic scene: he stood immobile, though not in too stiff a pose, rather like parade rest; Graciela and the girls were crying.

I managed to keep myself calm and tried to calm the three women as well. Then I told Enrique Viani that if he agreed to my plan, I could make quick work of the invading spider. Opening his mouth just the least bit, so as not to send the slightest quiver through his leg muscle, Enrique Viani wondered:

"What plan?"

I explained. I'd take a razor blade and make a vertical slit downwards in his pants leg till I came to the spider, without even touching it. Once this was done, it would be easy for me to hit it with a rolled-up newspaper, knock it to the floor and then kill it or catch it.

"No, no," muttered Enrique Viani, desperate, but trying to restrain himself. "The pants leg will move and the spider will sting me. No, no, that's a terrible idea."

Stubborn people drive me up the wall. Without boasting, I can say my plan was perfect, and here this wretch who'd made me miss my siesta just up and rejects it, for no serious reason and, to top it off, he's snotty about it.

"Then I don't know what on earth we'll do," said Graciela. "And just tonight we have Patricia's fifteenth birthday party ..."

"Congratulations," I said, and kissed the birthday girl.

"... and we can't let the guests see Enrique standing there like a statue."

"Besides, what will Alejandro say."

"Who's Alejandro?"

"My boyfriend," Patricia, predictably, answered.

"I've got an idea!" exclaimed Claudia, the little sister. "We can call Don Nicola and ..."

I want it clear that I wasn't exactly wild about Claudia's plan and had nothing to do with its being adopted. In fact, I was dead set against it. But everyone else was heartily in favor of it and Enrique Viani was more enthusiastic than anyone.

So Don Nicola showed up and right away, being a man of action and not words, he set to work. Quickly he mixed mortar and, brick by brick, built up around Enrique Viani a tall, thin cylinder. The tight fit of his living quarters, far from being a drawback, allowed Enrique Viani to sleep standing up with no fear of falling and losing his upright position. Then Don Nicola carefully plastered over the construction, applied a base and painted it moss green to blend in with the carpeting and chairs.

Still, Graciela - dissatisfied with the general effect of this mini obelisk in the living room - tried putting a vase of flowers on top of it and then an ornamental lamp. Undecided, she said:

"This mess will have to do for now. Monday I'll buy something decent-looking."

To keep Enrique Viani from getting too lonely, I thought of staying on for Patricia's party, but the thought of facing the music our young people are so fond of terrified me. Anyway, Don Nicola had taken care to make a little rectangular window in front of Enrique Viani's eyes, so he could keep entertained watching certain irregularities in the wall paint. So, seeing everything was normal, I said goodbye to the Vianis and Don Nicola and went back home.

In Buenos Aires back in those years we were all overwhelmed with duties and obligations: the truth is I almost forgot all about Enrique Viani. Finally, a couple of weeks ago, I managed to get free for a moment and went to call on him.

I found he was still living in his little obelisk, only now a splendid blue-flowering creeper had twined its runners and leaves all around it. I pulled a bit to one side some of the luxuriant greenery and through the little window I managed to spot a face so pale it was nearly transparent. Guessing the question I was about to ask, Graciela told me that, through a kind of wise adaptation to the new circumstances, nature had exempted Enrique Viani from all physical necessities.

I didn't want to leave without making one last plea for sanity. I asked Enrique Viani to be reasonable; after twenty-three months of being walled up, this spider of ours was surely dead, so, then, we could tear down Don Nicola's handiwork and ...

Enrique Viani had lost the power of speech or at any rate his voice could no longer be heard; he just said no desperately with his eyes.

Tired and, maybe, a bit sad, I left.

In general, I don't think about Enrique Viani. But lately, I recalled his situation two or three times, and I flared up with rebellion: ah, if those unjustified fears didn't have such a hold, you'd see how I'd grab a pickaxe and knock down that ridiculous structure of Don Nicola's; you'd see how, facing facts that spoke louder than words, Enrique Viani would end up agreeing his fears were groundless.

But, after these flareups, respect for my fellow-man wins out, and I realize I have no right to butt into other people's lives and deprive Enrique Viani of an advantage he so treasures.

5.0

Over the span of our human evolution we have developed a powerful capacity and instinct for fear – a faculty not only good but vitally necessary when we consider all those millions of years when we were the prey of leopards, tigers and other predators hunting us in the dark at night.

However, in our modern world, many the time when our fear can work against us, not only causing great physical as well as psychological harm, but, if unchecked, can take over, crippling and debilitating us, reducing our life to a shaking, terrified bundle of raw nerves. Thus, I have always found great wisdom in the words of Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev: “Fear is never a good counselor and victory over fear is the first spiritual duty of man.”

I recall my own boyhood fear. My bedroom was a converted attic, a long, narrow dimly-lit room with a ceiling slanting at odd angles. Every night became an adventure in dealing with my overly active imagination. And all those many horror films repeated again and again on television certainly didn’t help. This went on for years but eventually as a young adult, through the practice of meditation, I overcame my fear of the dark.

Perhaps my own wrestling with fear made me particularly attuned to understanding what others might be going through when held in the grip of their own fear. Whatever else you might say or think, one thing for sure – being incapacitated and debilitated by fear is no fun. If we ask: how far can fear incapacitate, debilitate or cripple? No better answer to this question than absurdist fiction writer Fernando Sorrentino's following story.

Poor Enrique Viani! Not only is Enrique literary held in check by his fear of a spider but his mindset is so rigid, his fear so intense, that even when the spider is no longer present, he is incapable of change since his entire identity has become entwined with the defense he has constructed. One of the more insightful tales I’ve come across. Here it is: