Scan barcode

glenncolerussell's reviews

1456 reviews

The Fall by Albert Camus

“One plays at being immortal and after a few weeks one doesn't even know whether or not one can hang on till the next day.”

― Albert Camus, The Fall

“A single sentence will suffice for modern man: he fornicated and read the newspapers.” So pronounces Jean-Baptiste Clamence, narrator of Albert Camus’s short novel during the first evening of a monologue he delivers to a stranger over drinks at a shabby Amsterdam watering hole. Then, during the course of several evenings, the narrator continues his musings uninterrupted; yes, that’s right, completely uninterrupted, since his interlocutor says not a word. At one point Clamence states, “Alcohol and women provided me, I admit, the only solace of which I was worthy.” Clamence, judge-penitent as he calls himself, speaks thusly because he has passed judgment upon himself and his life. His verdict: guilty on all counts.

And my personal reaction to Clamence’s monologue? Let me start with a quote from Carl Jung: “I have frequently seen people become neurotic when they content themselves with inadequate or wrong answers to the questions of life. They seek position, marriage, reputation, outward success of money, and remain unhappy and neurotic even when they have attained what they were seeking. Such people are usually confined within too narrow a spiritual horizon.” Camus gives us a searing portrayal of a modern man who is the embodiment of spiritual poverty – morose, alienated, isolated, empty.

I would think Greco-Roman philosophers like Cicero, Seneca, Epictetus, or Marcus Aurelius would challenge Clamence in his clams to know life: “I never had to learn how to live. In that regard, I already knew everything at birth.”. Likewise, the wisdom masters from the enlightenment tradition –- such as Nagarjuna, Bodhidharma and Milarepa -- would have little patience listening to a monologue delivered by a smellfungus and know-it-all black bile stinker.

I completed my reading of the novel, a slow, careful reading as is deserving of Camus. The Fall is indeed a masterpiece of concision and insight into the plight of modern human experience.

Here is a quote from the Wikipedia review: “Clamence, through his confession, sits in permanent judgment of himself and others, spending his time persuading those around him of their own unconditional guilt.”

Would you be persuaded?

5.0

“One plays at being immortal and after a few weeks one doesn't even know whether or not one can hang on till the next day.”

― Albert Camus, The Fall

“A single sentence will suffice for modern man: he fornicated and read the newspapers.” So pronounces Jean-Baptiste Clamence, narrator of Albert Camus’s short novel during the first evening of a monologue he delivers to a stranger over drinks at a shabby Amsterdam watering hole. Then, during the course of several evenings, the narrator continues his musings uninterrupted; yes, that’s right, completely uninterrupted, since his interlocutor says not a word. At one point Clamence states, “Alcohol and women provided me, I admit, the only solace of which I was worthy.” Clamence, judge-penitent as he calls himself, speaks thusly because he has passed judgment upon himself and his life. His verdict: guilty on all counts.

And my personal reaction to Clamence’s monologue? Let me start with a quote from Carl Jung: “I have frequently seen people become neurotic when they content themselves with inadequate or wrong answers to the questions of life. They seek position, marriage, reputation, outward success of money, and remain unhappy and neurotic even when they have attained what they were seeking. Such people are usually confined within too narrow a spiritual horizon.” Camus gives us a searing portrayal of a modern man who is the embodiment of spiritual poverty – morose, alienated, isolated, empty.

I would think Greco-Roman philosophers like Cicero, Seneca, Epictetus, or Marcus Aurelius would challenge Clamence in his clams to know life: “I never had to learn how to live. In that regard, I already knew everything at birth.”. Likewise, the wisdom masters from the enlightenment tradition –- such as Nagarjuna, Bodhidharma and Milarepa -- would have little patience listening to a monologue delivered by a smellfungus and know-it-all black bile stinker.

I completed my reading of the novel, a slow, careful reading as is deserving of Camus. The Fall is indeed a masterpiece of concision and insight into the plight of modern human experience.

Here is a quote from the Wikipedia review: “Clamence, through his confession, sits in permanent judgment of himself and others, spending his time persuading those around him of their own unconditional guilt.”

Would you be persuaded?

Ham on Rye by Charles Bukowski

I was sixteen, tan, blonde and good looking, catching waves on my yellow surfboard along with all the other surfers, handsome guys and beautiful gals, each and every day that summer. Little did I know this mini-heaven would quickly end and hell would begin in September. Why? My smooth-skinned tan face turned into an acne-filled mess. I suffered pimple by pimple for three years straight; many fat red pimples popping up every day. Oh, yeah, on my forehead, temples, cheeks, jaw, chin and nose. Unlike Charles Bukowski, my father never beat me as a kid but this was one thing I did have in common with Bukowski – being a teenager with a wicked case of acne. You can read all about his in this novel, Ham and Rye. Bukowski said, “The gods have really put a good shield over me man. I’ve been toughened up at the right time and the right place." Maybe this was part of my own toughening up, those three teenage years of enduring the red face fire of acne.

Anyway, this is one of my connections with Bukowski, the king of the hill when it comes to American raw-boned, hard-boiled, tough-guy writers. And this novel of his years as a kid and teenager growing up in a house where he was continually beaten with a leather strap and receiving a torrent of emotional abuses, particularly at the hands of his callous, obsessive father, sets the stage for his alcoholic, hardscrabble adulthood, an adulthood where, other than drinking, his sole refuge from childhood memories of cruelty and his ongoing life on the down-and-out edge was sitting at his typewriter composing poetry and fiction.

Ham on Rye. Every single sentence of this book is clear, vivid, sharp and direct, as if the words were bullets shot from a 22 caliber rifle. Here are just a few rounds: ““Words weren’t dull, words were things that could make your mind hum. If you read them and let yourself feel the magic, you could live without pain, with hope, no matter what happened to you.” Again, “I didn't like anybody in that school. I think they knew that. I think that's why they disliked me. I didn't like the way they walked or looked or talked, but I didn't like my mother or father either. I still had the feeling of being surrounded by white empty space. There was always a slight nausea in my stomach.” And, again. “The best thing about the bedroom was the bed. I liked to stay in bed for hours, even during the day with covers pulled up to my chin. It was good in there, nothing ever occurred in there, no people, nothing.”

Ham on Rye. There are funny, belly-laughing scenes and scenes that will make you shudder, scenes that are tender and scenes filled with pain, but through it all, you will stick with Hank Chinaski aka Charles Bukowski, the ultimate tough-guy with the heart of a poet.

5.0

I was sixteen, tan, blonde and good looking, catching waves on my yellow surfboard along with all the other surfers, handsome guys and beautiful gals, each and every day that summer. Little did I know this mini-heaven would quickly end and hell would begin in September. Why? My smooth-skinned tan face turned into an acne-filled mess. I suffered pimple by pimple for three years straight; many fat red pimples popping up every day. Oh, yeah, on my forehead, temples, cheeks, jaw, chin and nose. Unlike Charles Bukowski, my father never beat me as a kid but this was one thing I did have in common with Bukowski – being a teenager with a wicked case of acne. You can read all about his in this novel, Ham and Rye. Bukowski said, “The gods have really put a good shield over me man. I’ve been toughened up at the right time and the right place." Maybe this was part of my own toughening up, those three teenage years of enduring the red face fire of acne.

Anyway, this is one of my connections with Bukowski, the king of the hill when it comes to American raw-boned, hard-boiled, tough-guy writers. And this novel of his years as a kid and teenager growing up in a house where he was continually beaten with a leather strap and receiving a torrent of emotional abuses, particularly at the hands of his callous, obsessive father, sets the stage for his alcoholic, hardscrabble adulthood, an adulthood where, other than drinking, his sole refuge from childhood memories of cruelty and his ongoing life on the down-and-out edge was sitting at his typewriter composing poetry and fiction.

Ham on Rye. Every single sentence of this book is clear, vivid, sharp and direct, as if the words were bullets shot from a 22 caliber rifle. Here are just a few rounds: ““Words weren’t dull, words were things that could make your mind hum. If you read them and let yourself feel the magic, you could live without pain, with hope, no matter what happened to you.” Again, “I didn't like anybody in that school. I think they knew that. I think that's why they disliked me. I didn't like the way they walked or looked or talked, but I didn't like my mother or father either. I still had the feeling of being surrounded by white empty space. There was always a slight nausea in my stomach.” And, again. “The best thing about the bedroom was the bed. I liked to stay in bed for hours, even during the day with covers pulled up to my chin. It was good in there, nothing ever occurred in there, no people, nothing.”

Ham on Rye. There are funny, belly-laughing scenes and scenes that will make you shudder, scenes that are tender and scenes filled with pain, but through it all, you will stick with Hank Chinaski aka Charles Bukowski, the ultimate tough-guy with the heart of a poet.

The Scaffold and Other Cruel Tales by Auguste de Villiers de l'Isle-Adam

French dramatist, novelist and teller of tales, Auguste Villiers de L'Isle-Adam (1838-1889) was one of the most inventive, creative writers of the nineteenth century, Refusing to be pigeonholed, he placed a premium on imaginative, experimental storytelling, expanding his unique literary voice, a voice simultaneously behind and ahead of his time. As Brian Stableford notes in his introduction to this collection of over two dozen tales most peculiar and distinctive, "Villiers was always a writer who sought to avoid conventional themes and narrative frameworks; no matter how far his circumstances were reduced - and there were times when he went hungry for days - the one thing he was always determined to do was to write as no one had ever written before, experimenting with both narrative technique and subject matter." Below are snapshots from six of his extraordinary tales:

The Secret of the Scaffold

The famous Doctor Velpeau pays a visit to the cell of a condemned criminal, who, as it turns out, is also a medical man: Doctor Edmond-Desire Couty de la Pommerais. Since, as Doctor Velpeau explains, they are both men of science, a great benefit to society could be gained if he, Couty, would agree to give him, Velpeau, a special signal of awareness by blinking one eye after the fatal blow of the guillotine. When Couty hesitates, the good doctor asks Couty to think the matter over.

The next morning, prior to the condemned being led out to the scaffold, Doctor Velpeau returns. Thereupon seeing the esteemed physician, Couty exclaims: “I have been practicing – look! And while the order of execution was being read out, he held his right eyelid shut, while fixing the surgeon with the gaze of his wide-open left eye.” Now that’s Villiers-style black humor! -- in the name of science and progress, a doctor asks a man about to lose his life if he wouldn’t mind actively participating in a scientific experiment immediately after the guillotine chops off his head.

The Heroism of Doctor Hallidonhill

Villiers is a forerunner of the turn-of-the century literary Decadents, such as Joris-Karl Huysmans, Jean Lorrain, Octave Mirbeau, in his disdain for the positivist/scientific philosophy that was all the rage back in the late nineteenth century, a philosophy optimistically envisioning technology, science and modernism as the full flower of humanity and the savior of mankind.

In this tale, Doctor Hallidonhill will take any step necessary, no matter how ghastly or grisly, to contribute scientific and medical evidence for the improvement of mankind. Indeed, one of his patients walks into his office ravaged by nature: hacking, coughing, looking like a living skeleton. The good doctor proposes an exotic cure. Months later the patient, robust, radiating health, returns to thank Doctor Hallidonall, but his return proves to be a grave mistake; the patient has underestimated the doctor’s dedication to his practice above all else. This short tale could serve as the basis for a Philip K. Dick-style novel.

The Lovely Ardiane’s Secret

Here we have a tale where Villiers provides his own cynical twist to shatter the traditional notion that happiness flows from honesty and virtue. The young, innocent Ardiane, a Basque girl of humble origins, fall in love with a pale-skinned, bold-eyed virtuous guard by the name of Pier. Events transpire to bring the two lovers together -- they eventually marry and have a child. Ah, love; ah, romance. But wait – what exactly were the circumstances and events that transpired? Ardiane lays it all out to her Pier – she herself caused buildings to burn and neighbors to perish –all as a necessary step so she could meet and marry and have a child with Pier. Pier is initially horrified and turns against her, however, as Villiers writes: “But the Basque woman was so ardently beautiful that by five o’clock in the morning or thereabouts-too-persuasive desires having blinded the young man’s conscience little by little – her terrible campaign came to seem to him to be the endowments of a heroic heart. In brief, Pier Albrun weakened in the face of the delightful Ardiane Inferal- and forgave her.” Ah, love; ah, family!

The Elect of Dreams

Mediocre, uninspired, unartistic minds demand to see all, leaving nothing to the imagination; mediocre, uninspired, unartistic minds demand mechanical, naturalistic explanations, leaving nothing to the imagination. Such is the spirit of this charming Villiers tribute to a young poet, Alexis Dufrene, and the power of imagination to surpass all such mundane explanations.

The tale begins with Alexis in his garret joined by two friends, Breart, a painter and Nedonchel, a musician. These two friends hear a sound from an adjoining apartment and insist on seeing what is going on in there. Alexis blocks there way, exclaiming that beyond the door there is a king and his treasure and if they dare to enter and insist on seeing the resident of the apartment for themselves, they will never be real artists. The friends laugh, ignore his plea and barge right in. Alexis reflects: “Out of disdain for the Imaginary, which is the only reality for any artist, who knows how to command life to conform to it, they prefer to postpone their sensations until they can see what’s there.”

Continuing to value his imagination and dreams as if they were a treasure-chest of rare gems, later in the story, by a twist of great fortune, Alexis is handed a real treasure that enables the poet to travel to an exotic land and become a king. Meanwhile, what is the fate of his two friends? Villiers end the tale with these words: “Breart and Nedonchel are still in Paris. Both of them noble aesthetes, stay up late every evening in the depths of taverns haunted by the young writers of the future, to whom they strive to demonstrate, by means of theoretical conclusions that it is always necessary to see things as they are.” Indeed, Villiers pens this fairytale-like short story as a hymn to artistic imagination, which is most fitting since imagination was the author’s life-long polestar as he set about creating his own body of highly original writing.

That Mahoin!

Now here is a tale most cruel. A famous, infamous criminal is so unbelievably monstrous, so brutal, destructive, heinous, odious and wicked that when he is finally captured, his execution by guillotine draws thousands upon thousands of spectators, the entire town is too small to hold such a throng. But the public insists on seeing the spectacle. Men in the attics cut holes in the roofs and pop their heads out, eyes in the direction of the condemned man. Villiers writes: “Through the thousands of holes thus created thousands of talking but seemingly-decapitated heads appeared, directing their eyes towards the place of execution and fixing their gazes upon the bandit – without him being able for the moment, to comprehend where the bodies could be to which those heads belonged.” What happens next is a stroke (no pun intended) of storytelling genius. Thank you, Villiers de L’lsle-Adam!

Monsieur Redoux’s Phantasms

An odd tale. Upon leaving a dinner party in London where he is visiting, Monsieur Redoux, a corpulent businessman from Paris, finds himself in a wax museum. The museum is about to close, but in a fit of inspiration (or madness) Monsieur Redoux decides to stay among the wax figures since, after all, several of the wax figures are French Kings and Queens. As Villiers writes, “It was as if some kind of dark jester within his skull had suddenly shaken his bells- and he had not the slightest inclination to resist.”

One way of reading this tale is to see the author anticipating what psychologist Carl Jung termed the archetypes – the magician, the trickster, the king, the warrior, the lover – and how any one of these archetypes can overtake a personality as the trickster archetype overtakes the tale’s bourgeois Frenchman.

5.0

French dramatist, novelist and teller of tales, Auguste Villiers de L'Isle-Adam (1838-1889) was one of the most inventive, creative writers of the nineteenth century, Refusing to be pigeonholed, he placed a premium on imaginative, experimental storytelling, expanding his unique literary voice, a voice simultaneously behind and ahead of his time. As Brian Stableford notes in his introduction to this collection of over two dozen tales most peculiar and distinctive, "Villiers was always a writer who sought to avoid conventional themes and narrative frameworks; no matter how far his circumstances were reduced - and there were times when he went hungry for days - the one thing he was always determined to do was to write as no one had ever written before, experimenting with both narrative technique and subject matter." Below are snapshots from six of his extraordinary tales:

The Secret of the Scaffold

The famous Doctor Velpeau pays a visit to the cell of a condemned criminal, who, as it turns out, is also a medical man: Doctor Edmond-Desire Couty de la Pommerais. Since, as Doctor Velpeau explains, they are both men of science, a great benefit to society could be gained if he, Couty, would agree to give him, Velpeau, a special signal of awareness by blinking one eye after the fatal blow of the guillotine. When Couty hesitates, the good doctor asks Couty to think the matter over.

The next morning, prior to the condemned being led out to the scaffold, Doctor Velpeau returns. Thereupon seeing the esteemed physician, Couty exclaims: “I have been practicing – look! And while the order of execution was being read out, he held his right eyelid shut, while fixing the surgeon with the gaze of his wide-open left eye.” Now that’s Villiers-style black humor! -- in the name of science and progress, a doctor asks a man about to lose his life if he wouldn’t mind actively participating in a scientific experiment immediately after the guillotine chops off his head.

The Heroism of Doctor Hallidonhill

Villiers is a forerunner of the turn-of-the century literary Decadents, such as Joris-Karl Huysmans, Jean Lorrain, Octave Mirbeau, in his disdain for the positivist/scientific philosophy that was all the rage back in the late nineteenth century, a philosophy optimistically envisioning technology, science and modernism as the full flower of humanity and the savior of mankind.

In this tale, Doctor Hallidonhill will take any step necessary, no matter how ghastly or grisly, to contribute scientific and medical evidence for the improvement of mankind. Indeed, one of his patients walks into his office ravaged by nature: hacking, coughing, looking like a living skeleton. The good doctor proposes an exotic cure. Months later the patient, robust, radiating health, returns to thank Doctor Hallidonall, but his return proves to be a grave mistake; the patient has underestimated the doctor’s dedication to his practice above all else. This short tale could serve as the basis for a Philip K. Dick-style novel.

The Lovely Ardiane’s Secret

Here we have a tale where Villiers provides his own cynical twist to shatter the traditional notion that happiness flows from honesty and virtue. The young, innocent Ardiane, a Basque girl of humble origins, fall in love with a pale-skinned, bold-eyed virtuous guard by the name of Pier. Events transpire to bring the two lovers together -- they eventually marry and have a child. Ah, love; ah, romance. But wait – what exactly were the circumstances and events that transpired? Ardiane lays it all out to her Pier – she herself caused buildings to burn and neighbors to perish –all as a necessary step so she could meet and marry and have a child with Pier. Pier is initially horrified and turns against her, however, as Villiers writes: “But the Basque woman was so ardently beautiful that by five o’clock in the morning or thereabouts-too-persuasive desires having blinded the young man’s conscience little by little – her terrible campaign came to seem to him to be the endowments of a heroic heart. In brief, Pier Albrun weakened in the face of the delightful Ardiane Inferal- and forgave her.” Ah, love; ah, family!

The Elect of Dreams

Mediocre, uninspired, unartistic minds demand to see all, leaving nothing to the imagination; mediocre, uninspired, unartistic minds demand mechanical, naturalistic explanations, leaving nothing to the imagination. Such is the spirit of this charming Villiers tribute to a young poet, Alexis Dufrene, and the power of imagination to surpass all such mundane explanations.

The tale begins with Alexis in his garret joined by two friends, Breart, a painter and Nedonchel, a musician. These two friends hear a sound from an adjoining apartment and insist on seeing what is going on in there. Alexis blocks there way, exclaiming that beyond the door there is a king and his treasure and if they dare to enter and insist on seeing the resident of the apartment for themselves, they will never be real artists. The friends laugh, ignore his plea and barge right in. Alexis reflects: “Out of disdain for the Imaginary, which is the only reality for any artist, who knows how to command life to conform to it, they prefer to postpone their sensations until they can see what’s there.”

Continuing to value his imagination and dreams as if they were a treasure-chest of rare gems, later in the story, by a twist of great fortune, Alexis is handed a real treasure that enables the poet to travel to an exotic land and become a king. Meanwhile, what is the fate of his two friends? Villiers end the tale with these words: “Breart and Nedonchel are still in Paris. Both of them noble aesthetes, stay up late every evening in the depths of taverns haunted by the young writers of the future, to whom they strive to demonstrate, by means of theoretical conclusions that it is always necessary to see things as they are.” Indeed, Villiers pens this fairytale-like short story as a hymn to artistic imagination, which is most fitting since imagination was the author’s life-long polestar as he set about creating his own body of highly original writing.

That Mahoin!

Now here is a tale most cruel. A famous, infamous criminal is so unbelievably monstrous, so brutal, destructive, heinous, odious and wicked that when he is finally captured, his execution by guillotine draws thousands upon thousands of spectators, the entire town is too small to hold such a throng. But the public insists on seeing the spectacle. Men in the attics cut holes in the roofs and pop their heads out, eyes in the direction of the condemned man. Villiers writes: “Through the thousands of holes thus created thousands of talking but seemingly-decapitated heads appeared, directing their eyes towards the place of execution and fixing their gazes upon the bandit – without him being able for the moment, to comprehend where the bodies could be to which those heads belonged.” What happens next is a stroke (no pun intended) of storytelling genius. Thank you, Villiers de L’lsle-Adam!

Monsieur Redoux’s Phantasms

An odd tale. Upon leaving a dinner party in London where he is visiting, Monsieur Redoux, a corpulent businessman from Paris, finds himself in a wax museum. The museum is about to close, but in a fit of inspiration (or madness) Monsieur Redoux decides to stay among the wax figures since, after all, several of the wax figures are French Kings and Queens. As Villiers writes, “It was as if some kind of dark jester within his skull had suddenly shaken his bells- and he had not the slightest inclination to resist.”

One way of reading this tale is to see the author anticipating what psychologist Carl Jung termed the archetypes – the magician, the trickster, the king, the warrior, the lover – and how any one of these archetypes can overtake a personality as the trickster archetype overtakes the tale’s bourgeois Frenchman.

The Last Bar In NYC by Brian Michels

One man’s odyssey growing up in bars, working in bars and finally owning his own bar. And that’s not just in any city but New York City. Read all about it in Brian Michels novel memoir where a large bulk of the action in this novel in all likelihood, believe it or not, actually happened. And happened to Brian. To provide not a taste but a string of drinks to whet your thirst, below are a number of novel New York Cocktail or is that Nutty Irishman or Naked Margarita quotes along with my brief comments:

“My father had me perched at the far end of that bar top on a Saturday afternoon with a couple of cohorts standing around. He told me I was a natural, had everyone smiling and I was quick with my hands, premium traits for a barman.” ---------- You think you have a tough life? How about spending a good chunk of your childhood in a bar including the time when you’re five years old and a guy comes in and sticks a gun in your belly demanding you empty your pockets?

“Don’t let anyone tell you that everyone has talent and it’s just waiting to be discovered. Unless you consider talent the ability to open a bottle of beer or crack open a handful of peanuts; which would still leave the talent team a few men short for a warranted competition. Bottom line is plenty of people are without an ounce of talent.” ---------- And that bottom line has an implicit moral: what it takes in life if you have to work for a living is effort with a capital “E.”

“My will had always been tangible and provided nominal results that satisfied menial goals. But willpower must be a more discernable part; it should be what identifies a person, even more than character, personality or smarts. It’s the ultimate boss of you. It is you.” ---------- Again, that’s not only effort but continuous effort over a long hall.

“Working all night in a club required energy so cocaine was an integral part of the job. Lazy flakes and nerds would be thinned from the work force quickly. You had to have talent too because it wasn’t just about pouring drinks and making sure the bar is supplied. The right energy is what made a club great and the staff had as much to do with that as the owners, club designers, and DJs." ---------- This is the cocaine-fueled 1980s and if you are going to make it among the fast movers you’ll be expected to move your butt fast or get off the NYC bar train.

“A glitch, the pedestrian signal began flickering. Walk and Don’t Walk, and my brain deteriorated, hemorrhaged and everything inside of me liquefied. I couldn’t read any billboards, or recall one bit or thing of my squandered life.” ---------- Oh, my goodness. All that fast-paced energy fueled by cocaine and other substances, both legal and illegal, can take its toll on a guy’s system.

“A great change of pace to listen to guys with something relevant to say and maybe teach me a thing or two, or three, or four, or more. Rabbi Odd On was the smartest guy I ever served in a bar. He was a mathematician savant with a vast set of interests and could speak a dozen languages, probably more.” ---------- But you can bounce back and learn a few things along the way. Brian certainly did.

“They walloped me with baseball bats and took everything I had. I waited a week in the bus terminal all banged up sleeping on the floor and eating out of the garbage until my mother could wire me money she didn’t have for a ticket back to New York.” ---------- It has always been true. When you are in a fix or beaten up, literally or figuratively, always good to be able to call on friends or family to lend a hand. Most especially mom.

“It dawned on me that I had a real opportunity. They had to have hired more staff than needed because a smart boss doesn’t want to be left short-handed at the grand opening, and he’s want to see how an untested crew performs on their feet, sort them out.” ---------- A real opportunity, Brian! Not to be squandered as you’ve come to learn the hard way.

“Swallowing your pride can go down as easy as a worm bowl full of beef stock, onions, blood and cheese as long as you pretend it was your intended recipe. Even with a swollen tongue you can learn to gulp down yellow-bellied swill.” ---------- And you can gulp down some good old fashion learning by, among other things, immersing yourself in a whole bunch of good reading.

“The miracle happened on a miserable rainy night. Almost a dozen Professionals were yapping at the bar. A blood vessel in my left eye popped just as I heard the front door open and close with a thud.”” ---------- What’s Brian’s miracle? You’ll have to read this very readable, enjoyable, fast-paced story of one man’s journey into the Big Apple bar nights.

5.0

One man’s odyssey growing up in bars, working in bars and finally owning his own bar. And that’s not just in any city but New York City. Read all about it in Brian Michels novel memoir where a large bulk of the action in this novel in all likelihood, believe it or not, actually happened. And happened to Brian. To provide not a taste but a string of drinks to whet your thirst, below are a number of novel New York Cocktail or is that Nutty Irishman or Naked Margarita quotes along with my brief comments:

“My father had me perched at the far end of that bar top on a Saturday afternoon with a couple of cohorts standing around. He told me I was a natural, had everyone smiling and I was quick with my hands, premium traits for a barman.” ---------- You think you have a tough life? How about spending a good chunk of your childhood in a bar including the time when you’re five years old and a guy comes in and sticks a gun in your belly demanding you empty your pockets?

“Don’t let anyone tell you that everyone has talent and it’s just waiting to be discovered. Unless you consider talent the ability to open a bottle of beer or crack open a handful of peanuts; which would still leave the talent team a few men short for a warranted competition. Bottom line is plenty of people are without an ounce of talent.” ---------- And that bottom line has an implicit moral: what it takes in life if you have to work for a living is effort with a capital “E.”

“My will had always been tangible and provided nominal results that satisfied menial goals. But willpower must be a more discernable part; it should be what identifies a person, even more than character, personality or smarts. It’s the ultimate boss of you. It is you.” ---------- Again, that’s not only effort but continuous effort over a long hall.

“Working all night in a club required energy so cocaine was an integral part of the job. Lazy flakes and nerds would be thinned from the work force quickly. You had to have talent too because it wasn’t just about pouring drinks and making sure the bar is supplied. The right energy is what made a club great and the staff had as much to do with that as the owners, club designers, and DJs." ---------- This is the cocaine-fueled 1980s and if you are going to make it among the fast movers you’ll be expected to move your butt fast or get off the NYC bar train.

“A glitch, the pedestrian signal began flickering. Walk and Don’t Walk, and my brain deteriorated, hemorrhaged and everything inside of me liquefied. I couldn’t read any billboards, or recall one bit or thing of my squandered life.” ---------- Oh, my goodness. All that fast-paced energy fueled by cocaine and other substances, both legal and illegal, can take its toll on a guy’s system.

“A great change of pace to listen to guys with something relevant to say and maybe teach me a thing or two, or three, or four, or more. Rabbi Odd On was the smartest guy I ever served in a bar. He was a mathematician savant with a vast set of interests and could speak a dozen languages, probably more.” ---------- But you can bounce back and learn a few things along the way. Brian certainly did.

“They walloped me with baseball bats and took everything I had. I waited a week in the bus terminal all banged up sleeping on the floor and eating out of the garbage until my mother could wire me money she didn’t have for a ticket back to New York.” ---------- It has always been true. When you are in a fix or beaten up, literally or figuratively, always good to be able to call on friends or family to lend a hand. Most especially mom.

“It dawned on me that I had a real opportunity. They had to have hired more staff than needed because a smart boss doesn’t want to be left short-handed at the grand opening, and he’s want to see how an untested crew performs on their feet, sort them out.” ---------- A real opportunity, Brian! Not to be squandered as you’ve come to learn the hard way.

“Swallowing your pride can go down as easy as a worm bowl full of beef stock, onions, blood and cheese as long as you pretend it was your intended recipe. Even with a swollen tongue you can learn to gulp down yellow-bellied swill.” ---------- And you can gulp down some good old fashion learning by, among other things, immersing yourself in a whole bunch of good reading.

“The miracle happened on a miserable rainy night. Almost a dozen Professionals were yapping at the bar. A blood vessel in my left eye popped just as I heard the front door open and close with a thud.”” ---------- What’s Brian’s miracle? You’ll have to read this very readable, enjoyable, fast-paced story of one man’s journey into the Big Apple bar nights.

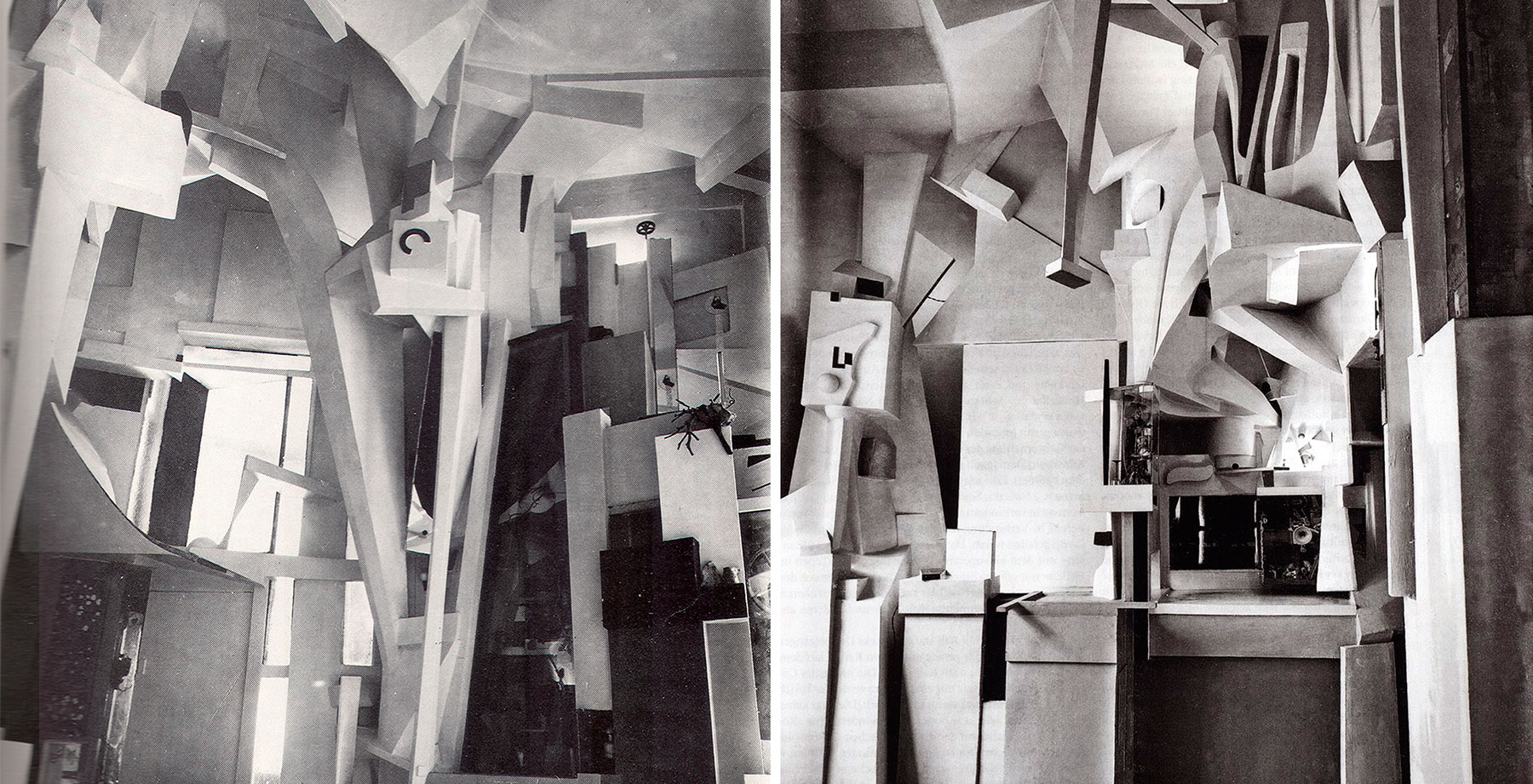

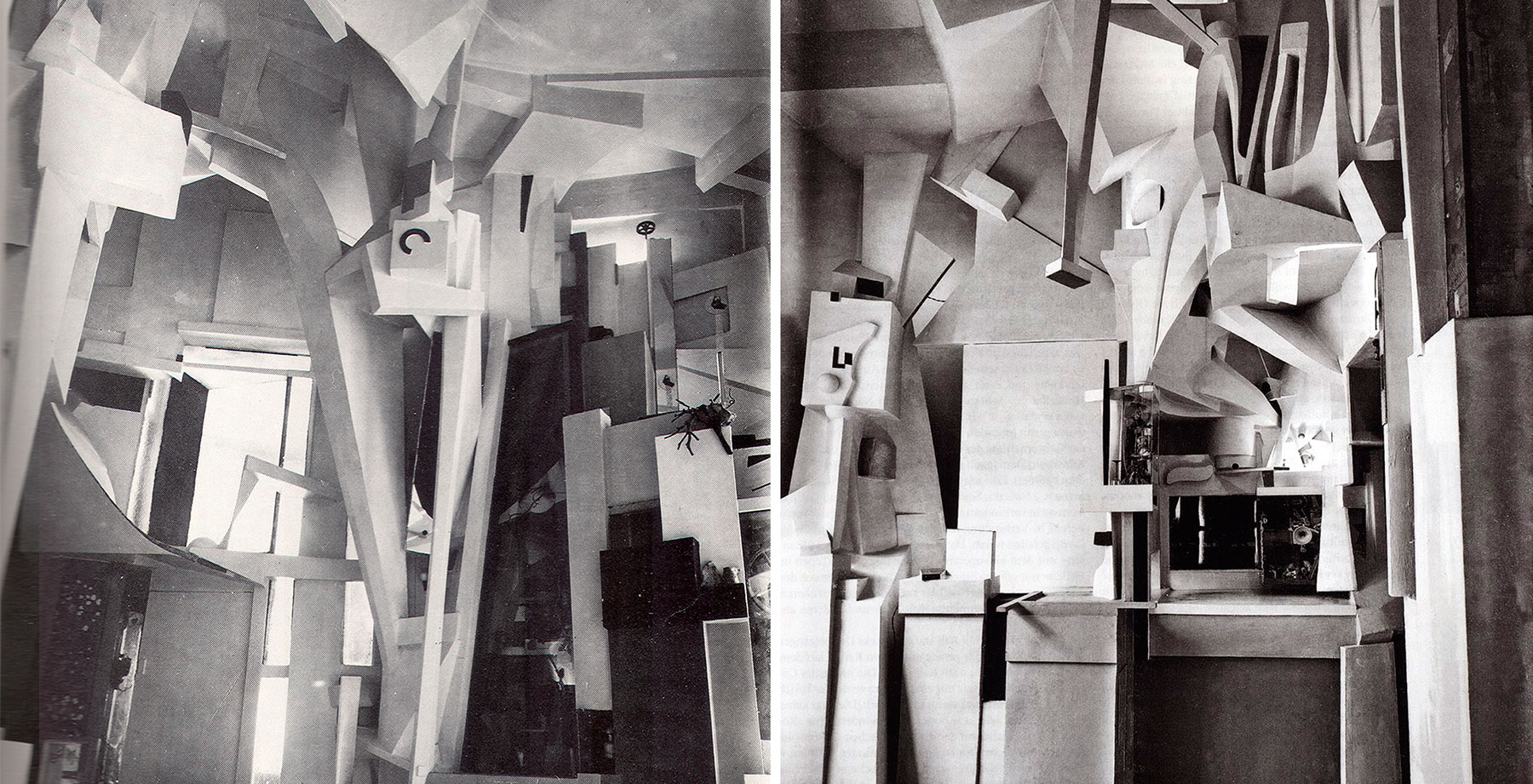

Kurt Schwitters by John Elderfield

Kurt Schwitters-Merzbau

Everything you ever wanted to know about the great German experimental artist Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948), to be sure. John Elderfield provides 300 pages of cultural and historical context along with the artistic development of this most original of creators. At one point he writes, “Schwitters talked a great deal of wanting to combine all the arts in a synthesis . . . In practice, however, what he did mainly was “to efface the boundaries between the arts” not in fact by linking all of them together, but by applying the common principle of assemblage to each of the arts he worked in.” Included in this large art book are over 300 illustrations, not only of Schwitters’s art but also various artists of the era, such as Andre Breton and Raoul Hausmann. What a treasure.

This book can fire the imagination. After reading some years ago myself, I was inspired to create my own Kurt Schwitters-style construction. Here are the notes I found in the diary I was keeping back then:

Rather than running to a department store and buying my daughter the dollhouse she’s been asking for, I decide to build one myself, a dollhouse to end all dollhouses, a dollhouse not only granting her wish for having a place for her miniature people and miniature furniture, but a dollhouse enabling me to fulfill my lifelong dream, albeit on a small scale, of creating a space similar to that great German Dada/Merz artist Kurt Schwitters, who turned virtually every available square foot of his home in Hanover into a sprawling no-objects-bared work of art. As he stated at one point, "My 'ultimate aspiration’ being ‘the union of art and non-art in the Merz total world view.'"

So, after sweating through an entire week of measuring, sawing, nailing and painting, I finished constructing the dollhouse, which I thereafter gave to my daughter as a present. She was delighted to finally have a dollhouse of her very own. Almost her own, that is, for during those first nights, after I tucked her in bed, I proceeded to build a sculpture construction out of toothpicks and matchboxes in one of the little upstairs dollhouse bedrooms.

Initially, my daughter found it curious, her daddy making “little cuties” in her dollhouse, places where her little doll family could sit and play. But the more I worked on the dollhouse, the more infatuated I became. It was if the spirit of Kurt Schwitters and other Dadaists came to not only inhabit but also haunt the little rooms of the dollhouse.

I cracked the little kitchen window and used a felt-tip pen to mark the smashed glass. This became my doll-sized version of Duchamp’s ‘The Bride Stripped Bare of Her Bachelors, Even.' I molded a tiny urinal out of clay, fastened it upside down to a dining room wall and wrote ‘Fountain’ underneath. Then, using glue and photographs reduced in size, I covered the little ceilings, walls and floors with collage and photomontage. I included every variety of discarded scrap I could put my hands on to fill every available space.

And, since I ran out of room in the dollhouse itself, I even took my daughter’s little dollhouse dolls and made random attachments of tacks, tape, springs and pins to their heads, thus creating multiple miniature versions of the Dadaist head of Raoul Hausmann.

Meanwhile, my daughter has been having mixed reactions. At times she enjoys all the new, unexpected tricks her made-over dolls can do in their full-to-the-brim dollhouse. But at other times, she is frustrated about the lack of empty space.

I can only hope she’ll eventually be happy, or at least tolerant. For, like Kurt Schwitters, who continued to build, combine and add until he constructed himself into a corner of his house and became a flesh-and-blood extension of his unending collage, my fingers have taken to dancing and building on their own.

And, after all, I will have to follow the lead of my fingers and work non-stop at night, starting in the corner of our downstairs family room where my daughter keeps her dollhouse next to a stack of teddy bears. Lucky for me and my family, I suppose, that it will take many more toothpicks, matchboxes, marbles, clay figures, wooden blocks, springs, tea sets, spools and string before my fingers take me to the stairway and the other rooms of our house.

5.0

Kurt Schwitters-Merzbau

Everything you ever wanted to know about the great German experimental artist Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948), to be sure. John Elderfield provides 300 pages of cultural and historical context along with the artistic development of this most original of creators. At one point he writes, “Schwitters talked a great deal of wanting to combine all the arts in a synthesis . . . In practice, however, what he did mainly was “to efface the boundaries between the arts” not in fact by linking all of them together, but by applying the common principle of assemblage to each of the arts he worked in.” Included in this large art book are over 300 illustrations, not only of Schwitters’s art but also various artists of the era, such as Andre Breton and Raoul Hausmann. What a treasure.

This book can fire the imagination. After reading some years ago myself, I was inspired to create my own Kurt Schwitters-style construction. Here are the notes I found in the diary I was keeping back then:

Rather than running to a department store and buying my daughter the dollhouse she’s been asking for, I decide to build one myself, a dollhouse to end all dollhouses, a dollhouse not only granting her wish for having a place for her miniature people and miniature furniture, but a dollhouse enabling me to fulfill my lifelong dream, albeit on a small scale, of creating a space similar to that great German Dada/Merz artist Kurt Schwitters, who turned virtually every available square foot of his home in Hanover into a sprawling no-objects-bared work of art. As he stated at one point, "My 'ultimate aspiration’ being ‘the union of art and non-art in the Merz total world view.'"

So, after sweating through an entire week of measuring, sawing, nailing and painting, I finished constructing the dollhouse, which I thereafter gave to my daughter as a present. She was delighted to finally have a dollhouse of her very own. Almost her own, that is, for during those first nights, after I tucked her in bed, I proceeded to build a sculpture construction out of toothpicks and matchboxes in one of the little upstairs dollhouse bedrooms.

Initially, my daughter found it curious, her daddy making “little cuties” in her dollhouse, places where her little doll family could sit and play. But the more I worked on the dollhouse, the more infatuated I became. It was if the spirit of Kurt Schwitters and other Dadaists came to not only inhabit but also haunt the little rooms of the dollhouse.

I cracked the little kitchen window and used a felt-tip pen to mark the smashed glass. This became my doll-sized version of Duchamp’s ‘The Bride Stripped Bare of Her Bachelors, Even.' I molded a tiny urinal out of clay, fastened it upside down to a dining room wall and wrote ‘Fountain’ underneath. Then, using glue and photographs reduced in size, I covered the little ceilings, walls and floors with collage and photomontage. I included every variety of discarded scrap I could put my hands on to fill every available space.

And, since I ran out of room in the dollhouse itself, I even took my daughter’s little dollhouse dolls and made random attachments of tacks, tape, springs and pins to their heads, thus creating multiple miniature versions of the Dadaist head of Raoul Hausmann.

Meanwhile, my daughter has been having mixed reactions. At times she enjoys all the new, unexpected tricks her made-over dolls can do in their full-to-the-brim dollhouse. But at other times, she is frustrated about the lack of empty space.

I can only hope she’ll eventually be happy, or at least tolerant. For, like Kurt Schwitters, who continued to build, combine and add until he constructed himself into a corner of his house and became a flesh-and-blood extension of his unending collage, my fingers have taken to dancing and building on their own.

And, after all, I will have to follow the lead of my fingers and work non-stop at night, starting in the corner of our downstairs family room where my daughter keeps her dollhouse next to a stack of teddy bears. Lucky for me and my family, I suppose, that it will take many more toothpicks, matchboxes, marbles, clay figures, wooden blocks, springs, tea sets, spools and string before my fingers take me to the stairway and the other rooms of our house.

The Truth in Painting by Geoff Bennington, Jacques Derrida, Geoffrey Bennington, Ian McLeod

5.0

MY FULL MICRONOVEL IS INCLUDED HERE

No question, there is a lot in this book, many ideas presented in complex, obscure language. But I persisted and read through to the end. On reflection, I thought it best to express my understanding of Derrida's main points in the form of the following micronovel. Special thanks to Goodreads friend Manny Rayner for helping me better understand the ideas in this Derrida book.

The Cannibals Read Jacques Derrida's The Truth in Painting -

A Postmodern Micronovel

One

A tribe of cannibals is reading Jacques Derrida's The Truth in Painting, the great French philosopher's prime work on art and aesthetics. The cannibals huddle around the fire, scrutinize the first lines and declare in unison how they will create paintings that are nothing but the truth.

Two

One cannibal says, “I am not only interested in painting; I am interested in the idiom in painting.” This launches an all-night heated discussion on the exact meaning of “idiom,” complete with quotation marks and quotation marks within quotation marks, all executed with adroit simultaneous rapid downward strokes of index and middle fingers of both hands. The result: there’s consensus among the cannibals: they will paint in the idiom of cannibal painting and they will always speak of their painting in the language of cannibals.

Three

Paul Cézanne said how he owed us the truth of painting and will tell it to us. The artist’s words served to underscore how he would gaze intensely at a subject, apply his brushstrokes and construct a picture rather than paint it. The cannibals muse over this section of Derrida’s book and wonder how they will likewise tell the viewer the truth of painting.

Four

What is the difference between an artist painting the truth and writing down in words how he owes it to the viewer to paint the truth? Reflecting on just this question, one cannibal proclaims, “Starting tomorrow, we will paint the truth rather than stating verbally or writing down in language how we will paint the truth.” Using sophisticated hand gestures and head nodding, the other cannibals express their agreement.

Five

It’s springtime. I sit on the hillside, overlooking a green mountain. I’m reminded of Cezanne. Is there any other painter who captured a mountain nearly as vividly, constructing his canvas with bold individual brushstrokes? I wonder if any other civilization or society could produce such an artist even if it were to last a thousand years.

Six

In the middle of my reflection in that particular place I was filled with incongruous, impracticable thoughts, such as fancying I have been seeing Cezanne’s mountain in my mind’s eye as if getting drunk on the artist’s vision and wondering how his pledge to tell the truth in painting accords with a classical theory of speech, that he really means what he says and says what he means and how his words impacted an appreciative audience in his own day, art lovers around the world in our day and how his words will resonate at future times and in other civilizations; my wondering turned to a humming and then a singing of nonsense sounds, pretending each sound could take on a color and the colors were various shades of green, first dark forest green then becoming progressively lighter until reaching the lightest of limes.

Seven

How would I translate my nonsense sounds into another language? Is this question tied up with the whole issue of what it means to render? I wonder. What if I stated in writing I only wanted to sing nonsense that was true nonsense, no matter what the language? Would I be able to accomplish my goal with greater ease than an artist like Cezanne who only wanted to paint the truth?

Eight

After six straight weeks of painting nonstop, the cannibals stand back and behold their giant mural painted on the rock face of a mountain. Most of the colors are rich browns – russet, bronze, seal brown, sepia, earth yellow, burnt amber, cocoa, tan – highlighted by lines and circles of white or grey. Remarkable. They all acknowledge they have accomplished, as far as they can discern, truth in painting.

Nine

Their rock painting is truly enormous, over four hundred feet wide by sixty feet high. Enormous, striking, refined and nuanced, bold and imaginative. The cannibals, returning to Derrida’s The Truth in Painting read how aesthetic judgement must properly bear upon intrinsic beauty, not on finery and surrounds. Hence, Derrida continues, one must know how to determine the intrinsic, that is, what is framed, and know what one is excluding as frame and outside-the-frame. Since their gigantic rock painting is framed in a bold white line running around the entire painted, they think they have a beautiful work of art, one where no viewer would have any question or difficulty discerning what is framed and what is outside-the-frame.

Ten

The next portion of Derrida’s work addresses the colossal in art. The cannibals smile, knowing they have anticipated what the great philosopher says about size and art. And since colossal is one of the defining qualities of their efforts, they put down the book, thinking they should really quit while they are ahead. Also, they are a bit confused when reference is made to another philosopher by the name of Kant. None of the cannibals have read Kant previously.

Eleven

I walk along the path until I am struck: before me is a gigantic abstract painting on a rock face, a type of painting I have never before set eyes upon. It takes me the better part of an hour but I approach this colossal work. I make a move to touch what I smell as fresh paint. Someone behind me shouts, “Please do not touch!” I turn around. I’m face to face with three dozen cannibals.

Twelve

The cannibals approach. They tell me they spent the last six straight weeks painting and, so sorry to break the bad news - they are extremely hungry. I stay calm and inform them they can’t eat me since I am the author of the story of their reading Derrida and their painting and how, if they eat me, they will likewise perish, something they should have no difficulty grasping since they are familiar with the postmodern philosophy of Derrida and in postmodernism an author can speak directly to the story’s characters.

Thirteen

The cannibals reflect on my words and admit what I say is true. I ask them to please stand in front of their painting so I can take their picture, post it on the internet and make them famous. They agree, all smiles. I methodically pace back, whip out my phone, focus and click a whole bunch of times. I wave and they wave back. A few give me the thumbs up. I turn and head for the hills, fast.

Fourteen

Reflecting on the cannibals’ splendid painting, magnificent in execution and colossal in both color and form, I decide when back in Outer Europe I’ll seek out guidance from a few experts to dig deeper into art, into painting and into the truth. Those cannibals certainly knew their Derrida and now I walked in the glow of postmodern revelation: incumbent upon me to match their knowledge.

Fifteen

“First off, you must grasp how in the West, our use of such oppositions as reason versus emotion, man versus women, spirit versus nature, center versus edge are all destructive and hierarchal, false oppositions that have served to bolster a society keeping the power players in power.” So says Jean-Georges, scholar and philosopher specializing in Derrida’s The Truth in Painting. We’re drinking coffee at an outdoor café. I add more cream. I have a coffee on the bottom, cream on the top dichotomy. Since I do not want to drink a beverage that’s a symbol of a false opposition, I stir the cream into the coffee. “Now that’s a realized interrelationship,” Jean-Georges chimes, “One continuous creamy coffee. You’re catching on.”

Sixteen

I walk down the busy street, quite a beautiful city street, cafes, art galleries, small parks, quaint bookstores, I’m pleased to say, alternating walking in the middle of the sidewalk and the edge of the sidewalk, keeping in the spirit of giving equal weight to center and edge so as not enhance any of those false oppositions and thus feed the manipulation of destruction or hierarchy. Such moving back and forth can be exhausting. I reflect on a world of undifferentiated oneness, where there is no space between what I perceive as me and the external world, a world of complete, total, undifferentiated light and an intense feeling of total bliss. All of life as light, oneness and bliss. I’m jarred out of my reverie by the honking of a truck horn and move from the edge of the sidewalk back to the center.

Seventeen

The next block down, there are several men watching a martial arts demonstration in a dojo. It’s a pleasant evening and the dojo is open on the sidewalk side – a great view for anybody interested in martial arts. On the white mat in the dojo itself, a dozen pre-teen and teenage students sit in their grey martial arts uniforms on their knees in a row to the left; about ten adult men, also in grey uniform, sit on their knees in a row on the right – the master is giving a demonstration. His movements are graceful, cat-like. I don’t see it at first but now I do: he is holding what looks to me like a samurai sword with two flowing handkerchiefs attached to the hilt. In a whisper I ask the man on the end what’s this form of martial arts? In a low voice he answers: “Shaolin Kung Fu Plum-Blossom Saber.” The demonstration is impressive, obviously taking years of diligent practice. Then I have a shock of recognition. Can it be? Yes, there’s no question: the Shaolin Kung Fu Plum-Blossom Saber master is none other than the literary critic, James Wood.

Eighteen

“I must admit I never suspected James Wood was a Kung Fu master; I mean, I’ve read a couple of his books and seen him interviewed on YouTube and he never really struck me as the ninja or martial arts type.” I’m talking to Pablo, one of the men who was watching the demonstration. We are drinking coffee at a café. Pablo says, “I’ve never read any of his books but he really is a flawless master; I should know since I’ve been practicing Kendo and Tae Kwon Do for more than a dozen years. I can spot a mater in any of the martial arts in an instant. What’s your name?” I thought perhaps I would remain an unnamed narrator but since he asked, I tell Pablo my name is Thaddeus Oldfather and I’m a literary critic and art critic for the international magazine Vol Gratuit.

Nineteen

The new monthly issue of Vol Gratuit is out on the newsstands with my photos of the cannibals and their rock painting. Instant fame. The editors plan to post on the Vol Gratuit website once all the magazines (requiring a huge second printing) are gobbled up. Of course, since I also wrote an accompanying short one paragraph blurb recounting my chance encounter with the rock painting and cannibals, everybody in the media wants an interview. I tell them all to wait until next summer as an aura of mystery and mystique enhances art, something dearly needed in the visual arts here in our postmodern world. Meanwhile, I grow a beard, wear a safari hat, move apartments and go underground. I need time to learn more about Derrida and The Truth in Painting.

Twenty

The cannibals send a scout across the mountains to a town to scout out any media coverage for their rock painting. The scout has no trouble finding a copy of Vol Gratuit with a photo of their tribe standing in front of the rock painting on the cover. Also, the scout brings back a newspaper with headlines about the extraordinary work of art. Of course the scout didn’t have any trouble blending in with the townspeople since he was wearing a New York Yankees baseball cap and an Oakland Raiders jersey along with Converse classic white high top sneakers complements of a group of unfortunate tourists who lost their way in the mountains and were more than happy to hand over their baseball caps, sweatshirts, hiking boots and sneakers in return for not being cooked for dinner.

Twenty-One

The cannibals gobble up my article in Vol Gratuit; they can’t get enough of the fact that I stated emphatically and unequivocally I would not reveal the whereabouts of the tribe or the rock painting since the artists are entitled to privacy until that time if and when they themselves choose to make contact with the outside world and welcome visitors and art lovers. They also feast their eyes on the stunning photos of their rock painting, stunning, that is, since the Vol Gratuit visual department did wonders with my amateurish snaps. Such are the technologies of our postmodern world, the photos are works of art in their own right.

Twenty-Two

“Things can get confusing very quickly. As when Derrida begins by noting how someone standing outside the frame, that is, outside the context of painting, starts asking about the idiom of painting. Such out-of-the-frame questioning will create ambiguity, thus, a problem, since an ambiguous phrase gives rise to multiple interpretations.” Jean-Georges taps his finger on the café table. I take a sip of my creamy, well-stirred coffee.

Twenty-Three

The first thing I need to clarify for myself is the tern ‘idiom.’ Of course we have phrases like ‘kick the bucket’ which means something much different than literally kicking the bucket; in other words, someone would have to be familiar with the culture and context wherein such an idiom was used to understand the idiom. Similarly, in the world of art, a painter puts ‘the finishing touches’ on the painting before it is complete. One would have to know something about painting generally to understand what the finishing touches on a particular painting amounts to.

Twenty-Four

Following this logic, if someone unfamiliar with painting and art stands outside the frame and asks about the idiom of painting, they create ambiguity simply by their asking the question. And, of course, any answer they might be given will be unclear since they are outside rather than inside the world of painting. This would be like me asking an electrical engineer about the idiom of circuitry – whatever the engineer answers will sound to me like so much gobbledygook.

Twenty-Five

I convey my modest comprehension to Jean-Georges. He nods, takes a couple of sips from his coffee, black with sugar, and says, “Already Derrida has us puzzling over language and painting, painting and language, well beyond any simple, standard approach to speaking of these two topics. This bit of Derrida is well worth pondering.” After a long moment of shared silence he says, “Derrida turns to a second ambiguous statement, a statement where Cezanne wrote his friend that he owed him the truth in painting and will tell it to him. This type of statement or speech act is referred to as a performance utterance, a statement that does something, like a minister telling a couple he will pronounce them husband and wife on Saturday.”

Twenty-Six

“Derrida asks us to think about the frame. Let’s use the example of a painting and its frame. What does the frame do? What does the frame show?” I can’t quite put my finger on it, but Jean-George’s questions about the function of a frame strike me as a key to opening the door to The Truth in Painting.

Twenty-Seven

I’m at a bookstore. I see a notice for a Kung Fu demonstration to be held at the same dojo I watched James Wood give his demonstration. I mark the date and time. I’ve never done any martial arts myself but I don’t want to miss this event, James Wood or no James Wood. There was something pure, something harmonious and beautiful about that dojo, more than the master and disciples, as if inhabited by the spirit of past masters of the arts, not only the martial arts but all of the arts from the East.

Twenty-Eight

Summer has passed into fall and I’m still undercover. My blonde beard has grown quite full and my safari hat and I have become best friends. I have been reflecting on all the many points Jean-Georges has made on Derrida’s The Truth of Painting. I sense I have a much firmer grasp of the French philosopher’s aesthetic theory. I turn over each point in my mind until it is as fine and as sharp as a plumb blossom saber, the saber I’ve seen James Wood demonstrate on four separate occasions. I still can’t quite get over James’ mastery, a mastery every bit as stunning as his literary criticism.

Twenty-Nine

Is the truth in The Truth in Painting the thing itself, as in for example the cannibals’ rock painting where the brown shapes outlined by white and grey are all taken together? If so, then the truth of painting is disclosed without any coverings or veils or disguises - the truth is what you see before your very eyes.

Thirty

Is the truth in The Truth in Painting more on the level of representation? And that’s representation in two senses: firstly, the round shapes of the rock painting representing a deeper spiritual reality or dream world; and second, as in the enhanced Vol Gratuit photographs representing the rock painting in such a way as to reveal its deeper truth, for example, a clearer portrayal of what would be impossible to see in the original, particularly in the cannibals’ rock painting where the top parts would be difficult, if not impossible, to see from below.

Thirty-One

Is the truth in The Truth in Painting an active agent, opening an observer’s imagination to the many possibilities of the rock painting? In this sense, there are as many ‘truths’ contained in the rock painting as there are visual pictures in the imagination of onlookers.

Thirty-Two

Or is the truth in The Truth in Painting more about an open-ended discussion relating to the painting rather than simply the painting itself? So, for example, my listing possible interpretations of the truth contained in the rock painting, a more conceptual, philosophical overview is, in fact, the truth, a interpretation having a decidedly postmodern ring.

Thirty-Three

I sit at a café across the table from a gentleman who is supremely interested in my reflections and all I have learned about Derrida’s The Truth of Painting. I sip my creamy coffee; he sips his latte. We are both undercover, me with my beard and safari hat; him with his Yankees cap and Raiders sweatshirt.

Thirty-Four

Konia tells me he is particularly inclined to the truth of their rock painting in alternative one, as the forms and colors, and also alternative two, as a pointer to the dreamtime and spiritual realm. On the other hand, the truth of painting as those imaginary worlds envisioned by art lover as they look at the rock painting strikes him as a bit too new age touchy-feely. Same thing goes for the photographs of the painting, since the photos should be judged as photos and their rock painting as the work of art itself. Respecting the truth of painting as the compilation of philosophical concepts and reflections – he would have to ponder this type of intellectualizing and be back with me.

Thirty-Five

Konia says something interesting: how the rock painting required extraordinary dexterity and skill, a unique conquering of heights, how these very talents have been honed and developed by his tribe over generations. This adeptness and expertise should enter the equation for what is the truth in painting since, according to his logic, without the necessary skill and nimbleness and the overcoming of fear of heights, there would be no rock art.

My Micronovel continues in the first comment within the comment section below for chapters 36-49.

No question, there is a lot in this book, many ideas presented in complex, obscure language. But I persisted and read through to the end. On reflection, I thought it best to express my understanding of Derrida's main points in the form of the following micronovel. Special thanks to Goodreads friend Manny Rayner for helping me better understand the ideas in this Derrida book.

The Cannibals Read Jacques Derrida's The Truth in Painting -

A Postmodern Micronovel

One

A tribe of cannibals is reading Jacques Derrida's The Truth in Painting, the great French philosopher's prime work on art and aesthetics. The cannibals huddle around the fire, scrutinize the first lines and declare in unison how they will create paintings that are nothing but the truth.

Two

One cannibal says, “I am not only interested in painting; I am interested in the idiom in painting.” This launches an all-night heated discussion on the exact meaning of “idiom,” complete with quotation marks and quotation marks within quotation marks, all executed with adroit simultaneous rapid downward strokes of index and middle fingers of both hands. The result: there’s consensus among the cannibals: they will paint in the idiom of cannibal painting and they will always speak of their painting in the language of cannibals.

Three

Paul Cézanne said how he owed us the truth of painting and will tell it to us. The artist’s words served to underscore how he would gaze intensely at a subject, apply his brushstrokes and construct a picture rather than paint it. The cannibals muse over this section of Derrida’s book and wonder how they will likewise tell the viewer the truth of painting.

Four

What is the difference between an artist painting the truth and writing down in words how he owes it to the viewer to paint the truth? Reflecting on just this question, one cannibal proclaims, “Starting tomorrow, we will paint the truth rather than stating verbally or writing down in language how we will paint the truth.” Using sophisticated hand gestures and head nodding, the other cannibals express their agreement.

Five

It’s springtime. I sit on the hillside, overlooking a green mountain. I’m reminded of Cezanne. Is there any other painter who captured a mountain nearly as vividly, constructing his canvas with bold individual brushstrokes? I wonder if any other civilization or society could produce such an artist even if it were to last a thousand years.

Six

In the middle of my reflection in that particular place I was filled with incongruous, impracticable thoughts, such as fancying I have been seeing Cezanne’s mountain in my mind’s eye as if getting drunk on the artist’s vision and wondering how his pledge to tell the truth in painting accords with a classical theory of speech, that he really means what he says and says what he means and how his words impacted an appreciative audience in his own day, art lovers around the world in our day and how his words will resonate at future times and in other civilizations; my wondering turned to a humming and then a singing of nonsense sounds, pretending each sound could take on a color and the colors were various shades of green, first dark forest green then becoming progressively lighter until reaching the lightest of limes.

Seven

How would I translate my nonsense sounds into another language? Is this question tied up with the whole issue of what it means to render? I wonder. What if I stated in writing I only wanted to sing nonsense that was true nonsense, no matter what the language? Would I be able to accomplish my goal with greater ease than an artist like Cezanne who only wanted to paint the truth?

Eight

After six straight weeks of painting nonstop, the cannibals stand back and behold their giant mural painted on the rock face of a mountain. Most of the colors are rich browns – russet, bronze, seal brown, sepia, earth yellow, burnt amber, cocoa, tan – highlighted by lines and circles of white or grey. Remarkable. They all acknowledge they have accomplished, as far as they can discern, truth in painting.

Nine

Their rock painting is truly enormous, over four hundred feet wide by sixty feet high. Enormous, striking, refined and nuanced, bold and imaginative. The cannibals, returning to Derrida’s The Truth in Painting read how aesthetic judgement must properly bear upon intrinsic beauty, not on finery and surrounds. Hence, Derrida continues, one must know how to determine the intrinsic, that is, what is framed, and know what one is excluding as frame and outside-the-frame. Since their gigantic rock painting is framed in a bold white line running around the entire painted, they think they have a beautiful work of art, one where no viewer would have any question or difficulty discerning what is framed and what is outside-the-frame.

Ten

The next portion of Derrida’s work addresses the colossal in art. The cannibals smile, knowing they have anticipated what the great philosopher says about size and art. And since colossal is one of the defining qualities of their efforts, they put down the book, thinking they should really quit while they are ahead. Also, they are a bit confused when reference is made to another philosopher by the name of Kant. None of the cannibals have read Kant previously.

Eleven

I walk along the path until I am struck: before me is a gigantic abstract painting on a rock face, a type of painting I have never before set eyes upon. It takes me the better part of an hour but I approach this colossal work. I make a move to touch what I smell as fresh paint. Someone behind me shouts, “Please do not touch!” I turn around. I’m face to face with three dozen cannibals.

Twelve

The cannibals approach. They tell me they spent the last six straight weeks painting and, so sorry to break the bad news - they are extremely hungry. I stay calm and inform them they can’t eat me since I am the author of the story of their reading Derrida and their painting and how, if they eat me, they will likewise perish, something they should have no difficulty grasping since they are familiar with the postmodern philosophy of Derrida and in postmodernism an author can speak directly to the story’s characters.

Thirteen

The cannibals reflect on my words and admit what I say is true. I ask them to please stand in front of their painting so I can take their picture, post it on the internet and make them famous. They agree, all smiles. I methodically pace back, whip out my phone, focus and click a whole bunch of times. I wave and they wave back. A few give me the thumbs up. I turn and head for the hills, fast.

Fourteen

Reflecting on the cannibals’ splendid painting, magnificent in execution and colossal in both color and form, I decide when back in Outer Europe I’ll seek out guidance from a few experts to dig deeper into art, into painting and into the truth. Those cannibals certainly knew their Derrida and now I walked in the glow of postmodern revelation: incumbent upon me to match their knowledge.

Fifteen

“First off, you must grasp how in the West, our use of such oppositions as reason versus emotion, man versus women, spirit versus nature, center versus edge are all destructive and hierarchal, false oppositions that have served to bolster a society keeping the power players in power.” So says Jean-Georges, scholar and philosopher specializing in Derrida’s The Truth in Painting. We’re drinking coffee at an outdoor café. I add more cream. I have a coffee on the bottom, cream on the top dichotomy. Since I do not want to drink a beverage that’s a symbol of a false opposition, I stir the cream into the coffee. “Now that’s a realized interrelationship,” Jean-Georges chimes, “One continuous creamy coffee. You’re catching on.”

Sixteen

I walk down the busy street, quite a beautiful city street, cafes, art galleries, small parks, quaint bookstores, I’m pleased to say, alternating walking in the middle of the sidewalk and the edge of the sidewalk, keeping in the spirit of giving equal weight to center and edge so as not enhance any of those false oppositions and thus feed the manipulation of destruction or hierarchy. Such moving back and forth can be exhausting. I reflect on a world of undifferentiated oneness, where there is no space between what I perceive as me and the external world, a world of complete, total, undifferentiated light and an intense feeling of total bliss. All of life as light, oneness and bliss. I’m jarred out of my reverie by the honking of a truck horn and move from the edge of the sidewalk back to the center.

Seventeen

The next block down, there are several men watching a martial arts demonstration in a dojo. It’s a pleasant evening and the dojo is open on the sidewalk side – a great view for anybody interested in martial arts. On the white mat in the dojo itself, a dozen pre-teen and teenage students sit in their grey martial arts uniforms on their knees in a row to the left; about ten adult men, also in grey uniform, sit on their knees in a row on the right – the master is giving a demonstration. His movements are graceful, cat-like. I don’t see it at first but now I do: he is holding what looks to me like a samurai sword with two flowing handkerchiefs attached to the hilt. In a whisper I ask the man on the end what’s this form of martial arts? In a low voice he answers: “Shaolin Kung Fu Plum-Blossom Saber.” The demonstration is impressive, obviously taking years of diligent practice. Then I have a shock of recognition. Can it be? Yes, there’s no question: the Shaolin Kung Fu Plum-Blossom Saber master is none other than the literary critic, James Wood.

Eighteen

“I must admit I never suspected James Wood was a Kung Fu master; I mean, I’ve read a couple of his books and seen him interviewed on YouTube and he never really struck me as the ninja or martial arts type.” I’m talking to Pablo, one of the men who was watching the demonstration. We are drinking coffee at a café. Pablo says, “I’ve never read any of his books but he really is a flawless master; I should know since I’ve been practicing Kendo and Tae Kwon Do for more than a dozen years. I can spot a mater in any of the martial arts in an instant. What’s your name?” I thought perhaps I would remain an unnamed narrator but since he asked, I tell Pablo my name is Thaddeus Oldfather and I’m a literary critic and art critic for the international magazine Vol Gratuit.

Nineteen

The new monthly issue of Vol Gratuit is out on the newsstands with my photos of the cannibals and their rock painting. Instant fame. The editors plan to post on the Vol Gratuit website once all the magazines (requiring a huge second printing) are gobbled up. Of course, since I also wrote an accompanying short one paragraph blurb recounting my chance encounter with the rock painting and cannibals, everybody in the media wants an interview. I tell them all to wait until next summer as an aura of mystery and mystique enhances art, something dearly needed in the visual arts here in our postmodern world. Meanwhile, I grow a beard, wear a safari hat, move apartments and go underground. I need time to learn more about Derrida and The Truth in Painting.

Twenty

The cannibals send a scout across the mountains to a town to scout out any media coverage for their rock painting. The scout has no trouble finding a copy of Vol Gratuit with a photo of their tribe standing in front of the rock painting on the cover. Also, the scout brings back a newspaper with headlines about the extraordinary work of art. Of course the scout didn’t have any trouble blending in with the townspeople since he was wearing a New York Yankees baseball cap and an Oakland Raiders jersey along with Converse classic white high top sneakers complements of a group of unfortunate tourists who lost their way in the mountains and were more than happy to hand over their baseball caps, sweatshirts, hiking boots and sneakers in return for not being cooked for dinner.

Twenty-One

The cannibals gobble up my article in Vol Gratuit; they can’t get enough of the fact that I stated emphatically and unequivocally I would not reveal the whereabouts of the tribe or the rock painting since the artists are entitled to privacy until that time if and when they themselves choose to make contact with the outside world and welcome visitors and art lovers. They also feast their eyes on the stunning photos of their rock painting, stunning, that is, since the Vol Gratuit visual department did wonders with my amateurish snaps. Such are the technologies of our postmodern world, the photos are works of art in their own right.

Twenty-Two

“Things can get confusing very quickly. As when Derrida begins by noting how someone standing outside the frame, that is, outside the context of painting, starts asking about the idiom of painting. Such out-of-the-frame questioning will create ambiguity, thus, a problem, since an ambiguous phrase gives rise to multiple interpretations.” Jean-Georges taps his finger on the café table. I take a sip of my creamy, well-stirred coffee.

Twenty-Three

The first thing I need to clarify for myself is the tern ‘idiom.’ Of course we have phrases like ‘kick the bucket’ which means something much different than literally kicking the bucket; in other words, someone would have to be familiar with the culture and context wherein such an idiom was used to understand the idiom. Similarly, in the world of art, a painter puts ‘the finishing touches’ on the painting before it is complete. One would have to know something about painting generally to understand what the finishing touches on a particular painting amounts to.

Twenty-Four

Following this logic, if someone unfamiliar with painting and art stands outside the frame and asks about the idiom of painting, they create ambiguity simply by their asking the question. And, of course, any answer they might be given will be unclear since they are outside rather than inside the world of painting. This would be like me asking an electrical engineer about the idiom of circuitry – whatever the engineer answers will sound to me like so much gobbledygook.

Twenty-Five

I convey my modest comprehension to Jean-Georges. He nods, takes a couple of sips from his coffee, black with sugar, and says, “Already Derrida has us puzzling over language and painting, painting and language, well beyond any simple, standard approach to speaking of these two topics. This bit of Derrida is well worth pondering.” After a long moment of shared silence he says, “Derrida turns to a second ambiguous statement, a statement where Cezanne wrote his friend that he owed him the truth in painting and will tell it to him. This type of statement or speech act is referred to as a performance utterance, a statement that does something, like a minister telling a couple he will pronounce them husband and wife on Saturday.”

Twenty-Six