Scan barcode

glenncolerussell's reviews

1456 reviews

Max Ernst: Beyond Painting by Ulrich Bischoff

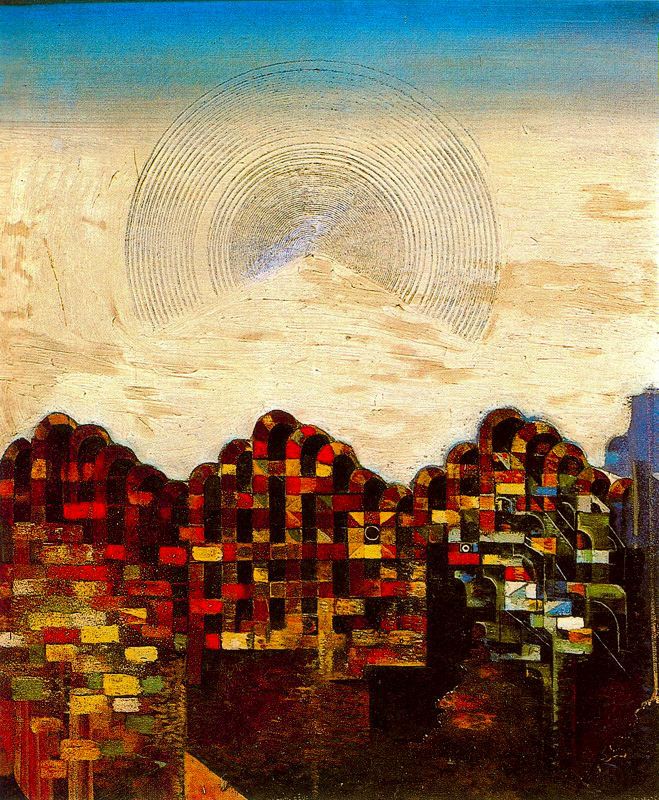

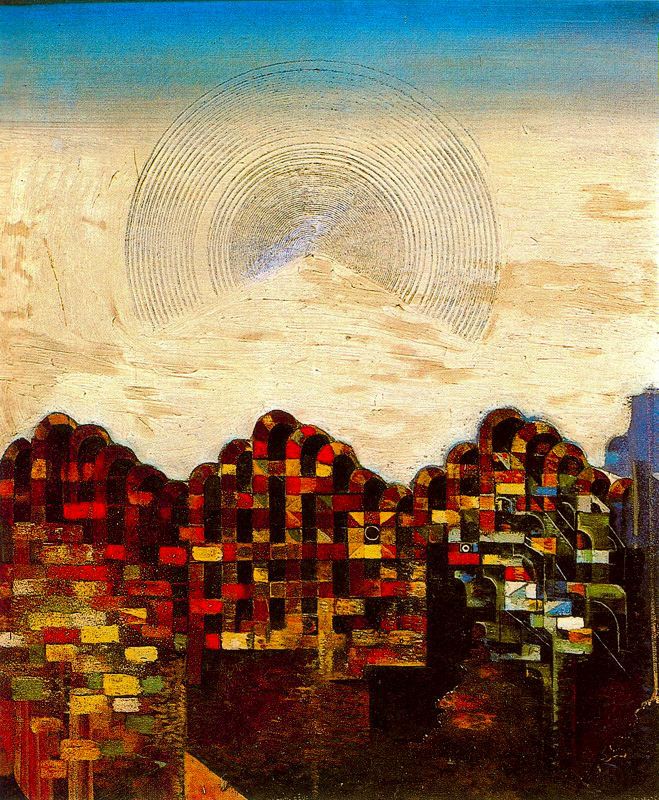

The Eye of Silence

Max Ernst: Beyond Painting. Ninety pages of artistic dynamite with an extended essay by art historian Ulrich Bischoff. Part of the Taschen series with dozens of pages filled with Max Ernst art, the majority in color, this volume offers a solid foundation for anyone interested in the artist’s life and work. Below are a number of direct quotes from the essay along with my comments:

“Max Ernst, who grew up in a petty bourgeois home in the Rhineland experienced art and culture either as an occupation for affluent citizens on Sundays and holidays, or as the dry object of investigation in the hands of art history professors.” ----------- His stuffy home in a small German town was simply the outermost shell, and a thin shell at that; what is critically important is how, even at a young age, Max Ernst possessed an imagination on fire with vision and a boundless sense of freedom, as in, for example, "Oedipus Rex, 1922."

“Ernst’s main means of escape was to make use of objects having little to do with art and to employ an absolutely new technique.” ---------- That’s “objects having little to do with art” from a coarse, conventional perspective, that is, objects men and women stuck in lackluster, petty categories would never remotely consider as part of art. However, for one of the most dynamic creators of the 20th century, everything he came in contact with, large and small, no matter how mundane or commonplace, as if base metal in an alchemist’s laboratory, could be worked and transformed into artistic gold. Case in Point: "Fruit of a Long Experience."

“The young student was interested in obscure fields of study and had a predilection for all kinds of strange, offbeat topics. His attempt to break away, which was mainly made possible by his use of chance and the unconscious, was a successful one.” --------- Ha! “Offbeat” and “strange” are relative terms. For an artistic imagination on fire, working within the confines of any approach blocking off the power of chance, accident, unforeseen possibilities or the bizarre is judged as so much stuffy prattle. Below; "The Murdering Airplane"

“Like a magician, Max Ernst the artist transformed whatever he touched, whether sacred or profane.” ---------- I couldn’t imagine an artist having more disregard for his own tradition and culture, even when that tradition and culture touches on elements of the sacred, than his painting “Young Virgin Spanking the Infant Jesus In Front of Three Witnesses.”

“Throughout the whole of Max Ernst’s works, hands play an important part. For the deaf, they are the main means of communication and since his father was a teacher of the deaf, Max Ernst was confronted with sign language from an early age.” ---------- How about that – watching his father teach sign language made a profound impact on young Max. Such attention to the delicacy of hand and fingers can be seen in his “At the First Clear Word.”

“His search for a technical means of avoiding a direct application of paint runs through his entire work, as do his efforts to carry out the picture itself and its subject with elements non-related to art. . . . In “Paris Dream” he used a wire comb to scrape two-thirds of a circle into the final surface of beige-grey paint, revealing a layer of blue below.” ---------- What I particularly enjoy about this painting is the contrast between the bold colors set out in a checkerboard grid across three mountains and the pale lightness of the upper half, the circle (actually many circles within circles) having echoes of an astrologer’s symbol for sun.

“The methods Max Ernst developed to stay “beyond” the classical way of painting taught at art schools have had an enormous influence on international art: collage, assemblage, montage, grattage, and decalcomania are techniques which he either developed himself or made us of in such a way that they soon became acceptable to both art schools and society alike.” ---------- The mark of a great artist is to leave the field you work in expanded and renewed. By my eye, the two works below are examples of the profound influence Max Ernst has had on the visual arts: “Europe after the Rain II” and “Capricorn.” Capricorn has a special appeal since Max appears with his honey!

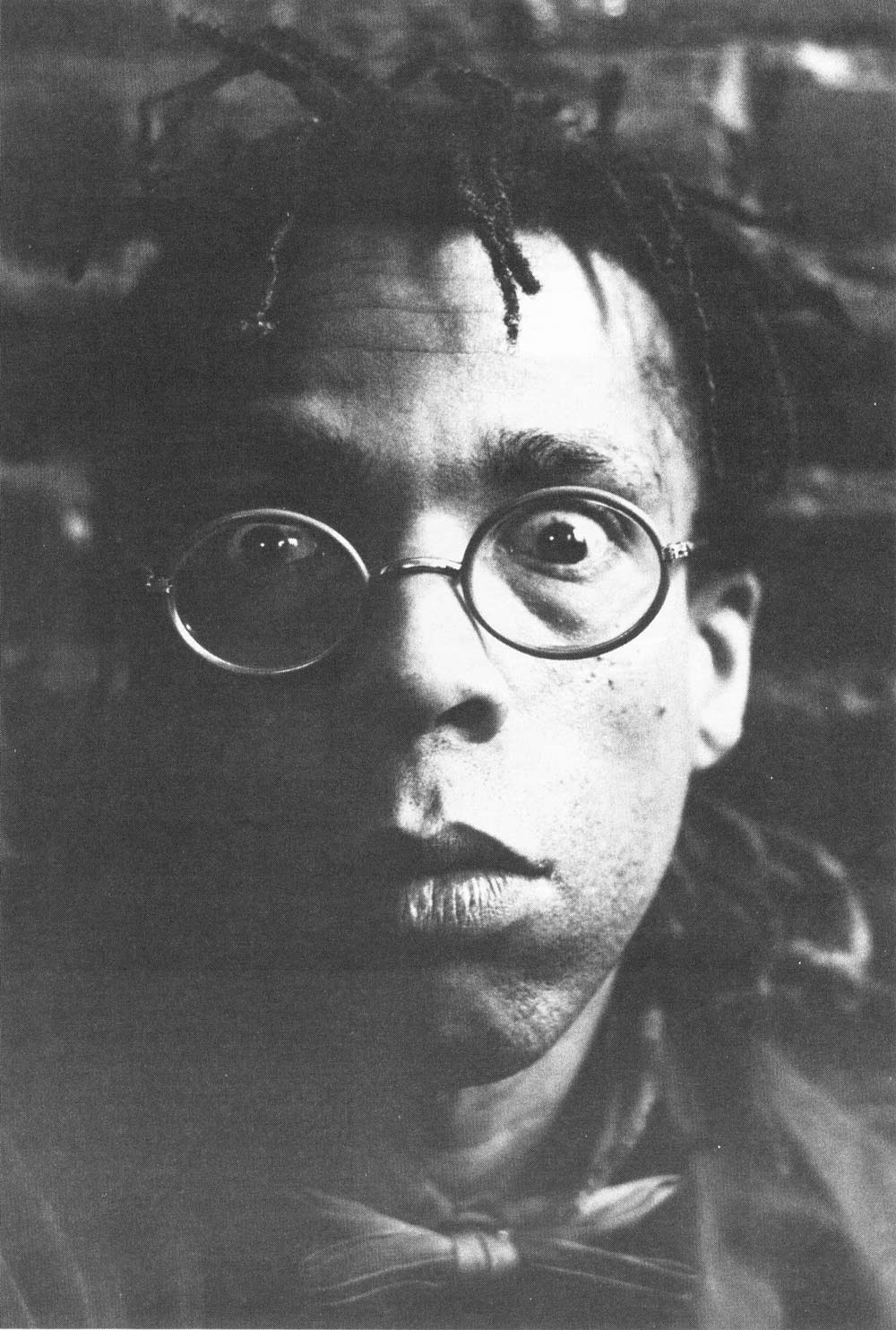

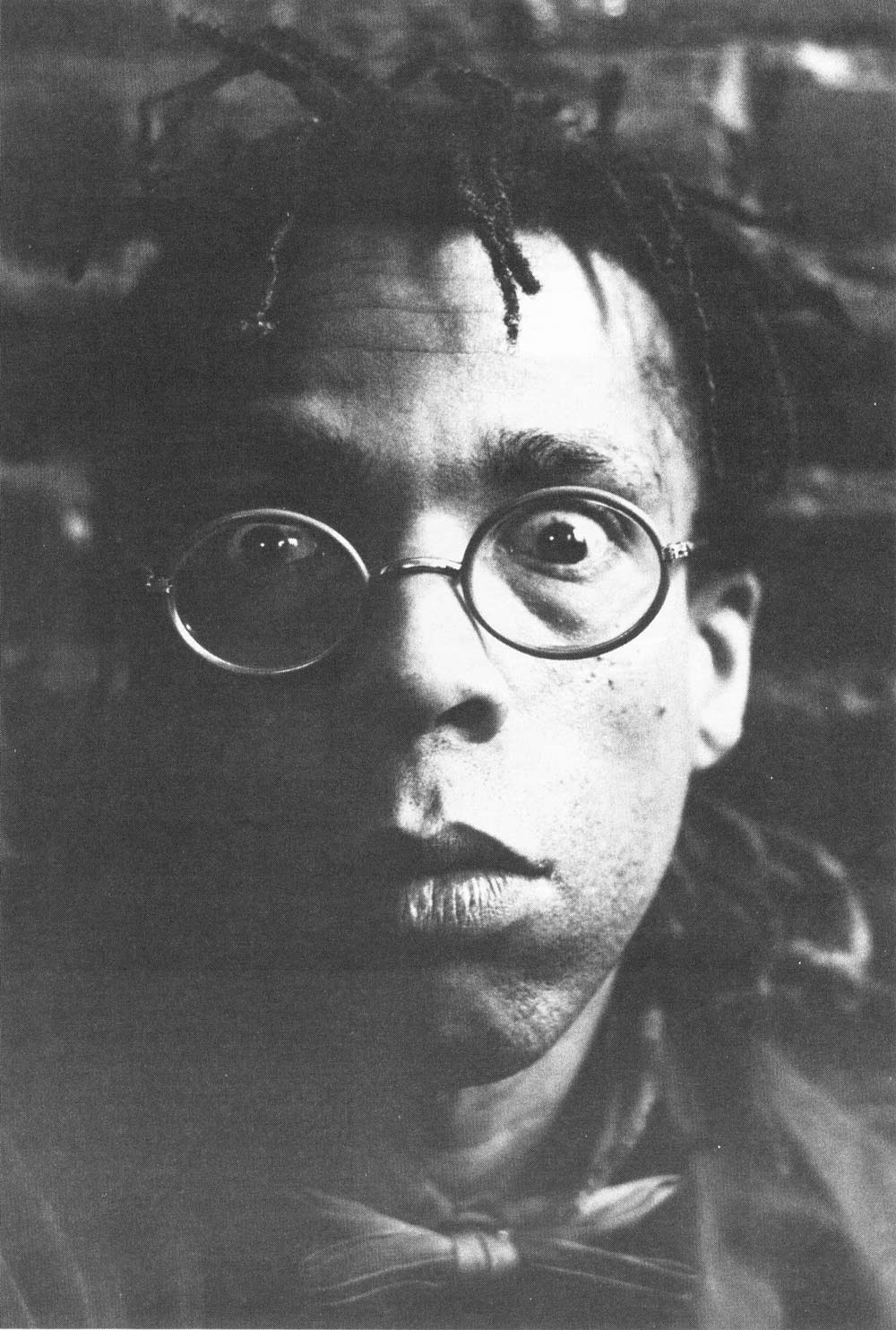

Photo of the Artist as a Young Man -- Max Ernst (1891-1976)

5.0

The Eye of Silence

Max Ernst: Beyond Painting. Ninety pages of artistic dynamite with an extended essay by art historian Ulrich Bischoff. Part of the Taschen series with dozens of pages filled with Max Ernst art, the majority in color, this volume offers a solid foundation for anyone interested in the artist’s life and work. Below are a number of direct quotes from the essay along with my comments:

“Max Ernst, who grew up in a petty bourgeois home in the Rhineland experienced art and culture either as an occupation for affluent citizens on Sundays and holidays, or as the dry object of investigation in the hands of art history professors.” ----------- His stuffy home in a small German town was simply the outermost shell, and a thin shell at that; what is critically important is how, even at a young age, Max Ernst possessed an imagination on fire with vision and a boundless sense of freedom, as in, for example, "Oedipus Rex, 1922."

“Ernst’s main means of escape was to make use of objects having little to do with art and to employ an absolutely new technique.” ---------- That’s “objects having little to do with art” from a coarse, conventional perspective, that is, objects men and women stuck in lackluster, petty categories would never remotely consider as part of art. However, for one of the most dynamic creators of the 20th century, everything he came in contact with, large and small, no matter how mundane or commonplace, as if base metal in an alchemist’s laboratory, could be worked and transformed into artistic gold. Case in Point: "Fruit of a Long Experience."

“The young student was interested in obscure fields of study and had a predilection for all kinds of strange, offbeat topics. His attempt to break away, which was mainly made possible by his use of chance and the unconscious, was a successful one.” --------- Ha! “Offbeat” and “strange” are relative terms. For an artistic imagination on fire, working within the confines of any approach blocking off the power of chance, accident, unforeseen possibilities or the bizarre is judged as so much stuffy prattle. Below; "The Murdering Airplane"

“Like a magician, Max Ernst the artist transformed whatever he touched, whether sacred or profane.” ---------- I couldn’t imagine an artist having more disregard for his own tradition and culture, even when that tradition and culture touches on elements of the sacred, than his painting “Young Virgin Spanking the Infant Jesus In Front of Three Witnesses.”

“Throughout the whole of Max Ernst’s works, hands play an important part. For the deaf, they are the main means of communication and since his father was a teacher of the deaf, Max Ernst was confronted with sign language from an early age.” ---------- How about that – watching his father teach sign language made a profound impact on young Max. Such attention to the delicacy of hand and fingers can be seen in his “At the First Clear Word.”

“His search for a technical means of avoiding a direct application of paint runs through his entire work, as do his efforts to carry out the picture itself and its subject with elements non-related to art. . . . In “Paris Dream” he used a wire comb to scrape two-thirds of a circle into the final surface of beige-grey paint, revealing a layer of blue below.” ---------- What I particularly enjoy about this painting is the contrast between the bold colors set out in a checkerboard grid across three mountains and the pale lightness of the upper half, the circle (actually many circles within circles) having echoes of an astrologer’s symbol for sun.

“The methods Max Ernst developed to stay “beyond” the classical way of painting taught at art schools have had an enormous influence on international art: collage, assemblage, montage, grattage, and decalcomania are techniques which he either developed himself or made us of in such a way that they soon became acceptable to both art schools and society alike.” ---------- The mark of a great artist is to leave the field you work in expanded and renewed. By my eye, the two works below are examples of the profound influence Max Ernst has had on the visual arts: “Europe after the Rain II” and “Capricorn.” Capricorn has a special appeal since Max appears with his honey!

Photo of the Artist as a Young Man -- Max Ernst (1891-1976)

A Man Jumps Out of an Airplane by Barry Yourgrau

Barry Yourgrau, born in South Africa in 1949 and living in New York City for many, many years

A book of dozens and dozens of one and two page micro-fictions where you will encounter bizarre happenings of all varieties, casts, shapes and sizes: a man climbs inside a cow, gentlemen in tuxedos perch in a tree, a couple of girls are locked up in an aquarium, a man comes home to find his wife in bed with a squirrel, there’s a bathtub filled with rutabagas, it snowing in a living room, a man rents two brown bears, sheep graze on a supermarket roof. Welcome to the world of Barry Yourgrau, located at the intersection of Freudian psychoanalysis, surrealist art and Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. But wait, enough with the generalizations; here are the openings lines from three twisted Barry snappers:

HULA HORROR

It’s very late at night – very early in the morning. I’m in a thatched-roof hut. Earthen floor. Kerosene lamp. A girl – a fellow tourist – has gotten drunk and is now dancing just for me, lasciviously as she can manage, in the middle of the place. She sways and bobs, come-hither style. She’s stripped off her clothing and is attired solely in a ‘native’ grass hula skirt, colored pink.

I drink, as I have copiously all evening; the gramophone squalls, the lamp throws a melodramatic light, harsh, utterly black in the shadows. I keep time with my glass, thinking, Man, the brochures don’t tell you about this, and then a horrible realizations pops into my mind, like a window shade flying up. That pink skirt, I realize, my skin turning icy – that pink skirt is hideously evil: it’s an instrument of black magic, a voodoo booby-trap planted here on us two boozed-up, wooly-brained tourists.

VILLAGE LIFE

Country girls, red-cheeked and buxom, stand feet wide apart at a counter. They lean on it, elbows propped, forearms crossed. They chat. Their skirts are gathered above their waists.

An old man plods down the line of them with a bucket. He reaches in between the thighs of each girl and puts the fruit he brings out into the bucket. The girls laugh. The atmosphere is easy. They mock the old man, they make cracks and someone ruffles his few hairs.

ARS POETICA

A man comes in. He has a glass throat. You can see his larynx in there: a microphone disk, a little speaker horn. A mailman comes in with his big bag. He opens the small transparent hatch in the man’s throat and pushes in a couple of blue air letters. The man beings to recite – a wonderful poem about being jealous of the clouds; then another poem, not quite as good, about a forbidden voyage.

“So this is how poetry is made,” I think. “What are some other ways?

------------------------------------

And as a mini-tribute to my love of Barry’s wildly inventive fiction, I wrote this little prose poem:

THE QUAGMIRE

Barry is stuck in a real quagmire. He just performed his act which ended with his mounting a sheep and afterwards slitting its throat and hurling the sheep out a third story window. The women organizers of his performance, much to his surprise, found his act disagreeable right from the start. They went ahead and called the police. The officers could see blood smeared all over the walls and floor. “Sir, we invited him to perform his flash fiction. We never expected anything like this!” In his turn, Barry told the officers about a bog of emotion and a marshland of gut feelings that must be expressed in more than just words. The police didn’t buy a word of it and hauled him away. What an abysmal ending to his performance. Barry has landed himself in a real quagmire. He has a nut to crack and no sheep to crack it with.

5.0

Barry Yourgrau, born in South Africa in 1949 and living in New York City for many, many years

A book of dozens and dozens of one and two page micro-fictions where you will encounter bizarre happenings of all varieties, casts, shapes and sizes: a man climbs inside a cow, gentlemen in tuxedos perch in a tree, a couple of girls are locked up in an aquarium, a man comes home to find his wife in bed with a squirrel, there’s a bathtub filled with rutabagas, it snowing in a living room, a man rents two brown bears, sheep graze on a supermarket roof. Welcome to the world of Barry Yourgrau, located at the intersection of Freudian psychoanalysis, surrealist art and Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. But wait, enough with the generalizations; here are the openings lines from three twisted Barry snappers:

HULA HORROR

It’s very late at night – very early in the morning. I’m in a thatched-roof hut. Earthen floor. Kerosene lamp. A girl – a fellow tourist – has gotten drunk and is now dancing just for me, lasciviously as she can manage, in the middle of the place. She sways and bobs, come-hither style. She’s stripped off her clothing and is attired solely in a ‘native’ grass hula skirt, colored pink.

I drink, as I have copiously all evening; the gramophone squalls, the lamp throws a melodramatic light, harsh, utterly black in the shadows. I keep time with my glass, thinking, Man, the brochures don’t tell you about this, and then a horrible realizations pops into my mind, like a window shade flying up. That pink skirt, I realize, my skin turning icy – that pink skirt is hideously evil: it’s an instrument of black magic, a voodoo booby-trap planted here on us two boozed-up, wooly-brained tourists.

VILLAGE LIFE

Country girls, red-cheeked and buxom, stand feet wide apart at a counter. They lean on it, elbows propped, forearms crossed. They chat. Their skirts are gathered above their waists.

An old man plods down the line of them with a bucket. He reaches in between the thighs of each girl and puts the fruit he brings out into the bucket. The girls laugh. The atmosphere is easy. They mock the old man, they make cracks and someone ruffles his few hairs.

ARS POETICA

A man comes in. He has a glass throat. You can see his larynx in there: a microphone disk, a little speaker horn. A mailman comes in with his big bag. He opens the small transparent hatch in the man’s throat and pushes in a couple of blue air letters. The man beings to recite – a wonderful poem about being jealous of the clouds; then another poem, not quite as good, about a forbidden voyage.

“So this is how poetry is made,” I think. “What are some other ways?

------------------------------------

And as a mini-tribute to my love of Barry’s wildly inventive fiction, I wrote this little prose poem:

THE QUAGMIRE

Barry is stuck in a real quagmire. He just performed his act which ended with his mounting a sheep and afterwards slitting its throat and hurling the sheep out a third story window. The women organizers of his performance, much to his surprise, found his act disagreeable right from the start. They went ahead and called the police. The officers could see blood smeared all over the walls and floor. “Sir, we invited him to perform his flash fiction. We never expected anything like this!” In his turn, Barry told the officers about a bog of emotion and a marshland of gut feelings that must be expressed in more than just words. The police didn’t buy a word of it and hauled him away. What an abysmal ending to his performance. Barry has landed himself in a real quagmire. He has a nut to crack and no sheep to crack it with.

Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings by Jorge Luis Borges

The stories, essays and parables in this Borges collection, with all their esoteric references to multiple histories, cultures and literatures, are no more likely to appeal to a casual reader then a textbook on cognitive psychology. To extract literary gold from highly intricate, complex works like The Garden of Forking Paths, Emma Zunz, The Library of Babel or The Zahir requires careful multiple readings as well as a willingness to occasionally investigate terms and references, for example here are several from The Zahir: The Book of Rites, Isaac Laquendem, The Nibelungen, the novel Confessions of a Thug, The Book of Things Unknown.

And, speaking of The Zahir, if I were to move from referring to the tale itself to the ideas which lie behind it, how would my review read? What does it mean for a narrator to dissolve the universe into a single coin? Why does Borges describe, right at the outset, how at different times in the past the Zahir, a coin he was handed in a bar, morphed into a tiger, a blind man, a small compass, a vein in the marble of a pillar, the bottom of a well? How does one compress all time into this one sentence I am now writing? And what of the philosophical and cultural context in which Borges wrote this tale? Could a first-person short-story like The Zahir have been written in Ancient China? Medieval Persia? Colonial America? These are questions that lie outside the framework of this Borges tale. Or do they?

Philosophical musing on the reality of the Zahir propels Borges (and us as readers) to multiple worlds: of a woman who seeks to makes every one of her actions correct to the point where she desires the absolute in the momentary; the dark light of the Gnostics; a dream where he, Borges the narrarator, becomes a pile of coins guarded by a gryphon. Then, after Borges’ fascination with the Zahir slides into obsession, driving him to seek out a psychiatrist, he writes, “Time, which softens memories, only makes the memory of the Zahir sharper. First I could see the face of it, then the reverse; now I can see both sides at once. It is not as though the Zahir were made of glass, since one side is not superimposed upon the other; rather it is as though the vision were spherical and the Zahir flutters in the center.”

Such refection bring to mind Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game, where the beads are, in fact, made of glass and can represent, in turn, cosmic topology, a fugue of celestial spheres, variations on relational placement as in the colors and lines of a Mondrian or circles with plasticity in Vasarely; only the Zahir has about it more unity then plurality, and thus one Möbius strip, one musical note, one painting, one print. Toward the very end we read: “Others will dream that I am mad, while I dream of the Zahir. When every person on earth thinks, day and night of the Zahir, which will be dream and which reality, the earth or the Zahir?”

Regarding the essays, Partial Magic in the Quixote opens us to a least a dozen unique angles in our approach to this Spanish classic; Kafka and His Precursors explores the connection of writers like Kierkegaard and Browning along with Zeno’s paradox to the famous author of The Metamorphosis; The Mirror of Enigmas delves into conundrums such as the symbolic significance of Sacred Scriptures and various forms of metaphysical writings as reflected on by, among others, Philo of Alexandria. Seven more essays will bend and stretch you mind in ways you never thought possible.

In the parable, Borges and I, the author conducts a dialogue with himself as well as, take your pick - author, public persona, alter ego, younger self, older self, second self – and is uncertain as he concludes his parable who exactly is the author of the lines he has just written. Everything and Nothing is a parable featuring Shakespeare with a multiple identity crisis; another parable, The Witness, has the narrator brooding over memory and death and yet in another parable, Inferno 1,32, we encounter a leopard, Dante, and God in what could be viewed as a dreamscape.

Reading Labyrinths years ago, I was inspired to write this micro-fiction as a tribute to Jorge Luis Borges:

LIFE STORY

The bold letters on the cover read: Harold Blackman – Life Story. The book looks quite ordinary. One is required to make a special inspection to see a queer spring-like device along the spine. Harold Blackman opens the book before him. The title page is completely blank as are all the pages. He runs gnarled fingers, tips calloused and slightly trembling, lightly over this ghost of a title page and reflects on the long agonizing nights when he tried to pen the fire of his youth and the spume of his manhood without success. What he saw when the ink dried always left him feeling flat, unsettled. Closing his eyes, he repeats an incantation learned from a half-crazed Argentine, then opens them slowly, very slowly. Harold Blackman, weary adventurer, is now standing on the writing table, shrunken to the size of the book. Lying down on the title page, the back of his legs, buttocks and backbone relax to the paper’s slight give. He released a catch on the spine, the leather cover snapping shut with the vengeance of a mousetrap. But for a muffled groan all is silence. Over time, the blood seeps through the pages, forming, words, sentences, paragraphs.

5.0

The stories, essays and parables in this Borges collection, with all their esoteric references to multiple histories, cultures and literatures, are no more likely to appeal to a casual reader then a textbook on cognitive psychology. To extract literary gold from highly intricate, complex works like The Garden of Forking Paths, Emma Zunz, The Library of Babel or The Zahir requires careful multiple readings as well as a willingness to occasionally investigate terms and references, for example here are several from The Zahir: The Book of Rites, Isaac Laquendem, The Nibelungen, the novel Confessions of a Thug, The Book of Things Unknown.

And, speaking of The Zahir, if I were to move from referring to the tale itself to the ideas which lie behind it, how would my review read? What does it mean for a narrator to dissolve the universe into a single coin? Why does Borges describe, right at the outset, how at different times in the past the Zahir, a coin he was handed in a bar, morphed into a tiger, a blind man, a small compass, a vein in the marble of a pillar, the bottom of a well? How does one compress all time into this one sentence I am now writing? And what of the philosophical and cultural context in which Borges wrote this tale? Could a first-person short-story like The Zahir have been written in Ancient China? Medieval Persia? Colonial America? These are questions that lie outside the framework of this Borges tale. Or do they?

Philosophical musing on the reality of the Zahir propels Borges (and us as readers) to multiple worlds: of a woman who seeks to makes every one of her actions correct to the point where she desires the absolute in the momentary; the dark light of the Gnostics; a dream where he, Borges the narrarator, becomes a pile of coins guarded by a gryphon. Then, after Borges’ fascination with the Zahir slides into obsession, driving him to seek out a psychiatrist, he writes, “Time, which softens memories, only makes the memory of the Zahir sharper. First I could see the face of it, then the reverse; now I can see both sides at once. It is not as though the Zahir were made of glass, since one side is not superimposed upon the other; rather it is as though the vision were spherical and the Zahir flutters in the center.”

Such refection bring to mind Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game, where the beads are, in fact, made of glass and can represent, in turn, cosmic topology, a fugue of celestial spheres, variations on relational placement as in the colors and lines of a Mondrian or circles with plasticity in Vasarely; only the Zahir has about it more unity then plurality, and thus one Möbius strip, one musical note, one painting, one print. Toward the very end we read: “Others will dream that I am mad, while I dream of the Zahir. When every person on earth thinks, day and night of the Zahir, which will be dream and which reality, the earth or the Zahir?”

Regarding the essays, Partial Magic in the Quixote opens us to a least a dozen unique angles in our approach to this Spanish classic; Kafka and His Precursors explores the connection of writers like Kierkegaard and Browning along with Zeno’s paradox to the famous author of The Metamorphosis; The Mirror of Enigmas delves into conundrums such as the symbolic significance of Sacred Scriptures and various forms of metaphysical writings as reflected on by, among others, Philo of Alexandria. Seven more essays will bend and stretch you mind in ways you never thought possible.

In the parable, Borges and I, the author conducts a dialogue with himself as well as, take your pick - author, public persona, alter ego, younger self, older self, second self – and is uncertain as he concludes his parable who exactly is the author of the lines he has just written. Everything and Nothing is a parable featuring Shakespeare with a multiple identity crisis; another parable, The Witness, has the narrator brooding over memory and death and yet in another parable, Inferno 1,32, we encounter a leopard, Dante, and God in what could be viewed as a dreamscape.

Reading Labyrinths years ago, I was inspired to write this micro-fiction as a tribute to Jorge Luis Borges:

LIFE STORY

The bold letters on the cover read: Harold Blackman – Life Story. The book looks quite ordinary. One is required to make a special inspection to see a queer spring-like device along the spine. Harold Blackman opens the book before him. The title page is completely blank as are all the pages. He runs gnarled fingers, tips calloused and slightly trembling, lightly over this ghost of a title page and reflects on the long agonizing nights when he tried to pen the fire of his youth and the spume of his manhood without success. What he saw when the ink dried always left him feeling flat, unsettled. Closing his eyes, he repeats an incantation learned from a half-crazed Argentine, then opens them slowly, very slowly. Harold Blackman, weary adventurer, is now standing on the writing table, shrunken to the size of the book. Lying down on the title page, the back of his legs, buttocks and backbone relax to the paper’s slight give. He released a catch on the spine, the leather cover snapping shut with the vengeance of a mousetrap. But for a muffled groan all is silence. Over time, the blood seeps through the pages, forming, words, sentences, paragraphs.

The Works of Théophile Gautier by Théophile Gautier

The Toilet of Venus by François Boucher (1703-1770)

Prior to turning to literature, Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) studied painting, which makes abundant sense since his writing is stunningly visual. For the purposes of my review, I will focus on one gem in this collection: Omphale: A Rococo Story. In order to fully appreciate the rich aesthetic texture of this Gautier tale, one should set one’s mood and mindset to the key of rococo. How to do this? Simple. Let your eyes drink in the beauty of the above magnificent portrait in the rococo style: The Toilet of Venus by François Boucher. In many ways this splendid painting can serve as the foundation for the spirit and essence of Gautier’s short story. All right, now you are ready for the story itself.

The narrator reflects back on a most memorable experience when he was a youth of seventeen: his visit to his uncle where he lodged in a separate structure built in 1700s rococo style, during the time of Louis XV, a building his uncle called Heart’s Delight, in honor, or perhaps dishonor, of naughty fleshy pleasures past. Indeed, his stern aristocratic uncle always judged reason to be king and had a ‘no nonsense’ view of life. We read, “If the old gentleman could have foreseen that my profession would be that of a writer of fantastic stories, I am quite sure he would have turned me out and disinherited me irrevocably, for he confessed the most aristocratic contempt for literature in general and authors in particular Like the true gentleman he was, he would have liked to have every one of the scribblers who makes it a business to spoil paper and to speak irreverently of people of quality, thrashed or hanged by his servants.”

So begins our rococo tale with a rococo building and rococo language used in the telling. For example, the narrator describes a portion of the interior room of this crumbling 1700s Louis XV-style building: “The bed hangings were of yellow silk damask with a pattern of great white flowers. A shell-work clock rested on a base inlaid with mother-of-pearl and ivory. A wreath of Burgundy roses wound coquettishly round a Venetian mirror and above the doors were painted in camaieu panels representing the four seasons.”

A truly rococo tale but a rococo tale told by the fiery 19th romantic, Théophile Gautier, who gives play to the fantastic - specifically in this tale, a truly fantastic event occurring in the space between dream and reality. One night, while dreaming (or, perhaps, barely awake), the 17 year old sees queen Omphale of the hanging tapestry come to life. The author writes, “The tapestry was violently agitated. Omphale left the wall, sprang lightly to the floor, came toward me, taking care to keep her face towards me. I fancy I need not enlarge on my amazement, the bravest veteran would have felt a bit queer under such conditions and I was neither old nor a soldier.”

Let’s pause to reflect on the power of portraiture in the long evolution of humankind. Going back to prehistoric cave paintings, the depiction of animal and human figures has always been infused with magical powers. And this power via artistic depiction continued throughout history, in nearly all societies and cultures, right up to the 1700s with such painters as François Boucher and Charles-André Van Loo (a rococo painter cited in this tale). 19th century authors appreciated the potency of art and incorporated its magic and power in their writing. Thus, this combination of portraiture and literature proved to be very, very powerful, indeed. Here are four examples of tales written in years following the publication of Gautier’s Omphale:

The Oval Portrait by Edgar Allan Poe – An artist paints his beautiful young wife’s portrait over the course of weeks. She sits patiently in the damp, posing as his model. He becomes so obsessed with instilling life-like perfection into his painting he is oblivious to his wife’s declining health. The moment he completes the portrait is the moment of his wife’s death.

The Picture of Dorian Gray – Classic tale of a handsome young man who sells his soul to the devil so his can ‘switch places’ with his portrait and have the painterly portrait age and fade while he retains youth and vitality.

The Portrait by Jean Richepin – A mediocre artist will sell his soul to the devil so he can paint one portrait that is a masterpiece. The deal is struck. Once his masterpiece is completed and sold, a portrait of a saint so illuminating and stunning the nuns who own the painting will only put the portrait on display during special holy days, the artist is found dead in his studio.

The Vengeance of the Oval Portrait by Gabriel de Lautrec – A nobleman falls in love with the portrait of a beautiful young woman. He attempts to bring the portrait to life via occult formulas and magic spells. All his efforts fail. Outraged and frustrated, he climbs a ladder, knife in hand, with the intent of hacking the portrait to pieces. At the point when he raises his knife, the portrait comes to life and strangles him in revenge for his killing her lover in years past. After this act of vengeance, the young lady reverts to her painterly state.

Ah, that combination of portraiture and tale-telling, so powerful, so magical. And no tale more magical than Théophile Gautier’s Omphale.

5.0

The Toilet of Venus by François Boucher (1703-1770)

Prior to turning to literature, Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) studied painting, which makes abundant sense since his writing is stunningly visual. For the purposes of my review, I will focus on one gem in this collection: Omphale: A Rococo Story. In order to fully appreciate the rich aesthetic texture of this Gautier tale, one should set one’s mood and mindset to the key of rococo. How to do this? Simple. Let your eyes drink in the beauty of the above magnificent portrait in the rococo style: The Toilet of Venus by François Boucher. In many ways this splendid painting can serve as the foundation for the spirit and essence of Gautier’s short story. All right, now you are ready for the story itself.

The narrator reflects back on a most memorable experience when he was a youth of seventeen: his visit to his uncle where he lodged in a separate structure built in 1700s rococo style, during the time of Louis XV, a building his uncle called Heart’s Delight, in honor, or perhaps dishonor, of naughty fleshy pleasures past. Indeed, his stern aristocratic uncle always judged reason to be king and had a ‘no nonsense’ view of life. We read, “If the old gentleman could have foreseen that my profession would be that of a writer of fantastic stories, I am quite sure he would have turned me out and disinherited me irrevocably, for he confessed the most aristocratic contempt for literature in general and authors in particular Like the true gentleman he was, he would have liked to have every one of the scribblers who makes it a business to spoil paper and to speak irreverently of people of quality, thrashed or hanged by his servants.”

So begins our rococo tale with a rococo building and rococo language used in the telling. For example, the narrator describes a portion of the interior room of this crumbling 1700s Louis XV-style building: “The bed hangings were of yellow silk damask with a pattern of great white flowers. A shell-work clock rested on a base inlaid with mother-of-pearl and ivory. A wreath of Burgundy roses wound coquettishly round a Venetian mirror and above the doors were painted in camaieu panels representing the four seasons.”

A truly rococo tale but a rococo tale told by the fiery 19th romantic, Théophile Gautier, who gives play to the fantastic - specifically in this tale, a truly fantastic event occurring in the space between dream and reality. One night, while dreaming (or, perhaps, barely awake), the 17 year old sees queen Omphale of the hanging tapestry come to life. The author writes, “The tapestry was violently agitated. Omphale left the wall, sprang lightly to the floor, came toward me, taking care to keep her face towards me. I fancy I need not enlarge on my amazement, the bravest veteran would have felt a bit queer under such conditions and I was neither old nor a soldier.”

Let’s pause to reflect on the power of portraiture in the long evolution of humankind. Going back to prehistoric cave paintings, the depiction of animal and human figures has always been infused with magical powers. And this power via artistic depiction continued throughout history, in nearly all societies and cultures, right up to the 1700s with such painters as François Boucher and Charles-André Van Loo (a rococo painter cited in this tale). 19th century authors appreciated the potency of art and incorporated its magic and power in their writing. Thus, this combination of portraiture and literature proved to be very, very powerful, indeed. Here are four examples of tales written in years following the publication of Gautier’s Omphale:

The Oval Portrait by Edgar Allan Poe – An artist paints his beautiful young wife’s portrait over the course of weeks. She sits patiently in the damp, posing as his model. He becomes so obsessed with instilling life-like perfection into his painting he is oblivious to his wife’s declining health. The moment he completes the portrait is the moment of his wife’s death.

The Picture of Dorian Gray – Classic tale of a handsome young man who sells his soul to the devil so his can ‘switch places’ with his portrait and have the painterly portrait age and fade while he retains youth and vitality.

The Portrait by Jean Richepin – A mediocre artist will sell his soul to the devil so he can paint one portrait that is a masterpiece. The deal is struck. Once his masterpiece is completed and sold, a portrait of a saint so illuminating and stunning the nuns who own the painting will only put the portrait on display during special holy days, the artist is found dead in his studio.

The Vengeance of the Oval Portrait by Gabriel de Lautrec – A nobleman falls in love with the portrait of a beautiful young woman. He attempts to bring the portrait to life via occult formulas and magic spells. All his efforts fail. Outraged and frustrated, he climbs a ladder, knife in hand, with the intent of hacking the portrait to pieces. At the point when he raises his knife, the portrait comes to life and strangles him in revenge for his killing her lover in years past. After this act of vengeance, the young lady reverts to her painterly state.

Ah, that combination of portraiture and tale-telling, so powerful, so magical. And no tale more magical than Théophile Gautier’s Omphale.

The Poet Assassinated by Guillaume Apollinaire

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), poet par excellence of the early 20th century Parisian literary world, inventor of the word "surrealism," champion of cubism and other innovative forms of modern art, wrote The Poet Assassinated in a hospital bed recovering from shrapnel wounds inflicted during World War One.

Reading this novella is like entering a dream world of a De Chirico cityscape or the montage of Max Ernst – and every couple of paragraphs the surreal panorama shifts – one of the most unique reading experiences one can encounter. With Apollinaire we have truly transitioned from the naturalism of Zola and the decadence of Huysmans into the Eiffel Tower world of modernity. Hello Picasso, hello Cubism, hello Dali Surrealism.

Apollinaire’s novella is comprised of 18 micro-chapters, all with one-word titles, such as Name, Nobility, Pedagogy, Poetry, Love, Fashion – like 18 pieces of torn paper, dropped randomly but not too randomly, fluttering down on a blank mat. In order to have a more intimate feel for the tone of this bizarre, whimsical work, please view Entr’acte, a short French 1924 black-and-white film by René Clair (easily located on YouTube) and featuring three well-known surrealist artists: Francis Picabia, Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp.

How powerful is your imagination? The author provides the mythic outline of the life of our main character, the god-like, world conquering poet Croniamanta, a man born in a year where his birth was saluted with an erection – the Eiffel Tower (sexual image directly from the text) but Apollinaire invites us to fill in the blanks and create our own version of Croniamanta. After all, even the place of his birth is claimed by no less than 127 towns and 7 countries!

Respecting that mythic outline we are given the following: Croniamanta’s mother died in childbirth and his father put a gun to his head after losing a fortune in a Monaco casino. He was raised by a well-learned man urging him to love all of nature and schooling him in Greek and Latin, the French of Racine, the English of Shakespeare and the Italian of Petrarch. Also, he was introduced to fencing and horsemanship, so by age 15 Croniamanta imagined himself as both knight and lover. At 21, poems in hand and filled with a love of literature, Croniamanta sets off for Paris where his eyes devoured everything and he eventually smashed eternity to pieces.

The great poet proclaims he will never write a poem again that is not free of all shackles, even the shackles of language. Croniamanta then becomes famous but enemies of poetry are on the rise. At one point a prophet tells him the earth can no longer stand its contact with poets. This is born out with the discovery that the United States has started electrocuting people who claim poetry as a profession. To add to this horror, Germany forbids all poets from going outdoors and four countries -- France, Italy, Spain, Portugal -- put all poets in jail. In Paris mobs are reported to have strangled poets in public.

Standing tall before an angry crowd, Croniamanta denounces all haters of poets as swine and murderers. But an angry crowd is an angry crowd; they turn on Croniamanta and kill him. In the aftermath a sculptor creates a monument to the great poet – a hole with reinforced concrete, the void in the ground has the shape of Croniamanta; the hole is filled but filled in a unique way: the hole is filled with Croniamanta’s phantom.

This brief sketch is like describing Salvador Dali’s Persistence of Memory as a number of flaccid watches out in the desert. This is surrealism; this is the realm of dreams; this is where the umbrella meets the sewing machine on the operating table; this is a novella by Guillaume Apollinaire. One is obliged to enter the work itself with fresh, open imagination.

5.0

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), poet par excellence of the early 20th century Parisian literary world, inventor of the word "surrealism," champion of cubism and other innovative forms of modern art, wrote The Poet Assassinated in a hospital bed recovering from shrapnel wounds inflicted during World War One.

Reading this novella is like entering a dream world of a De Chirico cityscape or the montage of Max Ernst – and every couple of paragraphs the surreal panorama shifts – one of the most unique reading experiences one can encounter. With Apollinaire we have truly transitioned from the naturalism of Zola and the decadence of Huysmans into the Eiffel Tower world of modernity. Hello Picasso, hello Cubism, hello Dali Surrealism.

Apollinaire’s novella is comprised of 18 micro-chapters, all with one-word titles, such as Name, Nobility, Pedagogy, Poetry, Love, Fashion – like 18 pieces of torn paper, dropped randomly but not too randomly, fluttering down on a blank mat. In order to have a more intimate feel for the tone of this bizarre, whimsical work, please view Entr’acte, a short French 1924 black-and-white film by René Clair (easily located on YouTube) and featuring three well-known surrealist artists: Francis Picabia, Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp.

How powerful is your imagination? The author provides the mythic outline of the life of our main character, the god-like, world conquering poet Croniamanta, a man born in a year where his birth was saluted with an erection – the Eiffel Tower (sexual image directly from the text) but Apollinaire invites us to fill in the blanks and create our own version of Croniamanta. After all, even the place of his birth is claimed by no less than 127 towns and 7 countries!

Respecting that mythic outline we are given the following: Croniamanta’s mother died in childbirth and his father put a gun to his head after losing a fortune in a Monaco casino. He was raised by a well-learned man urging him to love all of nature and schooling him in Greek and Latin, the French of Racine, the English of Shakespeare and the Italian of Petrarch. Also, he was introduced to fencing and horsemanship, so by age 15 Croniamanta imagined himself as both knight and lover. At 21, poems in hand and filled with a love of literature, Croniamanta sets off for Paris where his eyes devoured everything and he eventually smashed eternity to pieces.

The great poet proclaims he will never write a poem again that is not free of all shackles, even the shackles of language. Croniamanta then becomes famous but enemies of poetry are on the rise. At one point a prophet tells him the earth can no longer stand its contact with poets. This is born out with the discovery that the United States has started electrocuting people who claim poetry as a profession. To add to this horror, Germany forbids all poets from going outdoors and four countries -- France, Italy, Spain, Portugal -- put all poets in jail. In Paris mobs are reported to have strangled poets in public.

Standing tall before an angry crowd, Croniamanta denounces all haters of poets as swine and murderers. But an angry crowd is an angry crowd; they turn on Croniamanta and kill him. In the aftermath a sculptor creates a monument to the great poet – a hole with reinforced concrete, the void in the ground has the shape of Croniamanta; the hole is filled but filled in a unique way: the hole is filled with Croniamanta’s phantom.

This brief sketch is like describing Salvador Dali’s Persistence of Memory as a number of flaccid watches out in the desert. This is surrealism; this is the realm of dreams; this is where the umbrella meets the sewing machine on the operating table; this is a novella by Guillaume Apollinaire. One is obliged to enter the work itself with fresh, open imagination.

The Rooster's Wife by Russell Edson

A Portrait in Ellipses - illustration by prose poet Russell Edson, 1935–2014

What many readers enjoy about poetry is the heartfelt connection with the world of the poet through language, sensations, feelings, perceptions and musings contained within the poem. Even someone like myself who doesn’t usually read that much poetry, the three poems below resonate:

The Red Wheelbarrow by William Carlos Williams

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

How Poetry Comes to Me by Gary Snyder

It comes blundering over the

Boulders at night, it stays

Frightened outside the

Range of my campfire

I go to meet it at the

Edge of the light

Each Ecstatic Instant by Emily Dickinson

For each ecstatic instant

We must an anguish pay

In keen and quivering ratio

To the ecstasy.

For each beloved hour

Sharp pittances of years,

Bitter contested farthings

And coffers heaped with tears.

But what to make of the prose poems of Russell Edson, where the whole dynamic of poetry in the conventional sense is turned on its head? As Goodreads reviewer Nina observed, Edson uses his poems to play puppeteer with his characters, where men, women, animals, plant life and objects function as little more than dolls or “soulless stick figures against a blank backdrop.” And these bizarre Edson-esque happenings take place in an unnervingly chaotic, jumpy universe, a universe where interspecies sex, outlandish combinations and transformations along with outbreaks of random violence are all accepted as perfectly normal. It appears we are worlds away from the the poetry of William Carlos Williams, Gary Snyder and Emily Dickinson. Actually, more is at stake. As Charles Simic wrote in his New York Times Review of Russell Edson: "For many readers, calling something like this poetry is not just preposterous, but an insult against every poem they have ever loved."

So what does a Russell Edson prose poem look like? For those readers unacquainted, here is a sampling of four of his shorter pieces from this collection:

Fairytale

Behind every chicken is the story of a broken egg. And behind every broken egg is the story of a matron chicken. And behind every matron is another broken egg . . .

Out of the distance into the foreground they come, Hansels and Gretels dropping egg shells as they come . . .

The Elegant Simplification

An old man’s cane had broken a bone. Actually, a cane has only one bone. One of nature’s more elegant simplifications.

As the doctor prepared the splint he asked how the cane came to break its back.

My wife, said the old man. Her head is uncommonly hard . . .

Super Monkey

He was creating a super monkey by grafting pieces of a dead parrot to a morphine monkey.

When the monkey awoke he was covered with green feathers and had a beak. His first words were, Polly wants a cracker.

It’s historic! No monkey will ever have said this before!

And so super monkey will be given all the crackers super monkey can eat, until super monkey sickens of crackers and says, Polly wants a banana. Which will be another historic quotable!

Then he’ll begin work on super-duper monkey who, with proper grafting, will be able to sing like a canary . . .

The Tree

They have grafted pieces of an ape with pieces of a dog.

Then, what they have, wants to live in a tree.

No, what they have wants to lift its leg and piss on the tree . . .

Ouch! What in the world is going on with such poetry? As a dedicated lover of Russell Edson prose poems for the past thirty years, permit me to offer a few observations:

• Each piece tells a little story and the story is told in sentences rather than verse, thus a prose poem rather than a poem;

• We have entered the world of surrealism, the world where the umbrella meets the sewing machine on the operating table, the world where anything, no matter how bizarre, outlandish, weird, odd or strange, can take place and does take place;

• The combinations and happening are as clear as clear can be, in this way, these prose poems have much in common with the paintings of René Magritte;

• The imagination is touched in ways most fantastic – another magic gate to the worlds of hallucination, dream, visions and shamanism.

And how dedicated was Russell Edson to the prose poem? He wrote mostly prose poems – more than a dozen books of prose poems over a span of forty-five years. After reading my first Russell Edson poem years ago, I found my own writer’s voice and began writing prose poems for the next eight years. I’d like to share a couple:

Under the Desert Sun

Beyond the tuba of time and the trumpet of brass fittings, they spot a spiky green growth: a cactus with two bulbous swells toward the top – a female cactus, they reckon. Coming closer, they espy drops of dried blood on the sand a few inches from the green, spiky base. Ah, yes, it must be that time of month for the female plant.

By this tuba time, their own legs – green and spiky – can’t move. The sun, fiery ball, spins a child on the tip of its tongue.

The Adventures of Maurice Moonrat

A cartoonist keeps a caged moonrat in his studio. He had this creature, a variety of hedgehog, brought all the way from the Borneo so he could create the animated cartoon version with accuracy. The cartoonist carefully studies this foot-long moonrat with its small eyes and ears in a yellowish wedge-shaped head, its sharp, pointed nose bristling with long whiskers, its pointed teeth, its hairy, brown coat and long scaly tail. When he’s done, he names his cartoon character Maurice Moonrat.

The first episode will feature Maurice Moonrat and his sidekick, Lars, a dull-witted tomcat, bobsledding in the Olympics. The cartoonist wants as much realism as possible, so he talks his studio into sending him to Lake Placid to watch real bobsledders in action. Once at the bobsled run, however, he insists on strapping the moonrat to the front of the bobsled to gauge the rodent’s reaction. The perplexed bobsledders reluctantly agree.

After the run, at the bottom of the hill, the cartoonist unstraps his moonrat, who takes a few shaky steps and curls up in a shivering mass of fur. The bobsledders understand just how cruel and sadistic the cartoonist really is when he insists the moonrat be strapped to the bobsled for a second run. There’s a second run, all right, but it isn’t anything like the cartoonist expected.

By the time they’re all reassembled at the top of the hill, there’s the beginning of a conversion to animation. Maurice Moonrat and Lars are the bobsledders, wearing helmets and sleek uniforms, Maurice the driver, Lars the brakeman, and the cartoonist is tied to the back of the bobsled, to be dragged down the track behind them. Maurice and Lars push off, running at record speed and then hop in the bobsled as they start their decent. Maurice’s pointed teeth break into a wide grin when he hears a long, drawn-out scream from his creator.

5.0

A Portrait in Ellipses - illustration by prose poet Russell Edson, 1935–2014

What many readers enjoy about poetry is the heartfelt connection with the world of the poet through language, sensations, feelings, perceptions and musings contained within the poem. Even someone like myself who doesn’t usually read that much poetry, the three poems below resonate:

The Red Wheelbarrow by William Carlos Williams

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

How Poetry Comes to Me by Gary Snyder

It comes blundering over the

Boulders at night, it stays

Frightened outside the

Range of my campfire

I go to meet it at the

Edge of the light

Each Ecstatic Instant by Emily Dickinson

For each ecstatic instant

We must an anguish pay

In keen and quivering ratio

To the ecstasy.

For each beloved hour

Sharp pittances of years,

Bitter contested farthings

And coffers heaped with tears.

But what to make of the prose poems of Russell Edson, where the whole dynamic of poetry in the conventional sense is turned on its head? As Goodreads reviewer Nina observed, Edson uses his poems to play puppeteer with his characters, where men, women, animals, plant life and objects function as little more than dolls or “soulless stick figures against a blank backdrop.” And these bizarre Edson-esque happenings take place in an unnervingly chaotic, jumpy universe, a universe where interspecies sex, outlandish combinations and transformations along with outbreaks of random violence are all accepted as perfectly normal. It appears we are worlds away from the the poetry of William Carlos Williams, Gary Snyder and Emily Dickinson. Actually, more is at stake. As Charles Simic wrote in his New York Times Review of Russell Edson: "For many readers, calling something like this poetry is not just preposterous, but an insult against every poem they have ever loved."

So what does a Russell Edson prose poem look like? For those readers unacquainted, here is a sampling of four of his shorter pieces from this collection:

Fairytale

Behind every chicken is the story of a broken egg. And behind every broken egg is the story of a matron chicken. And behind every matron is another broken egg . . .

Out of the distance into the foreground they come, Hansels and Gretels dropping egg shells as they come . . .

The Elegant Simplification

An old man’s cane had broken a bone. Actually, a cane has only one bone. One of nature’s more elegant simplifications.

As the doctor prepared the splint he asked how the cane came to break its back.

My wife, said the old man. Her head is uncommonly hard . . .

Super Monkey

He was creating a super monkey by grafting pieces of a dead parrot to a morphine monkey.

When the monkey awoke he was covered with green feathers and had a beak. His first words were, Polly wants a cracker.

It’s historic! No monkey will ever have said this before!

And so super monkey will be given all the crackers super monkey can eat, until super monkey sickens of crackers and says, Polly wants a banana. Which will be another historic quotable!

Then he’ll begin work on super-duper monkey who, with proper grafting, will be able to sing like a canary . . .

The Tree

They have grafted pieces of an ape with pieces of a dog.

Then, what they have, wants to live in a tree.

No, what they have wants to lift its leg and piss on the tree . . .

Ouch! What in the world is going on with such poetry? As a dedicated lover of Russell Edson prose poems for the past thirty years, permit me to offer a few observations:

• Each piece tells a little story and the story is told in sentences rather than verse, thus a prose poem rather than a poem;

• We have entered the world of surrealism, the world where the umbrella meets the sewing machine on the operating table, the world where anything, no matter how bizarre, outlandish, weird, odd or strange, can take place and does take place;

• The combinations and happening are as clear as clear can be, in this way, these prose poems have much in common with the paintings of René Magritte;

• The imagination is touched in ways most fantastic – another magic gate to the worlds of hallucination, dream, visions and shamanism.

And how dedicated was Russell Edson to the prose poem? He wrote mostly prose poems – more than a dozen books of prose poems over a span of forty-five years. After reading my first Russell Edson poem years ago, I found my own writer’s voice and began writing prose poems for the next eight years. I’d like to share a couple:

Under the Desert Sun

Beyond the tuba of time and the trumpet of brass fittings, they spot a spiky green growth: a cactus with two bulbous swells toward the top – a female cactus, they reckon. Coming closer, they espy drops of dried blood on the sand a few inches from the green, spiky base. Ah, yes, it must be that time of month for the female plant.

By this tuba time, their own legs – green and spiky – can’t move. The sun, fiery ball, spins a child on the tip of its tongue.

The Adventures of Maurice Moonrat

A cartoonist keeps a caged moonrat in his studio. He had this creature, a variety of hedgehog, brought all the way from the Borneo so he could create the animated cartoon version with accuracy. The cartoonist carefully studies this foot-long moonrat with its small eyes and ears in a yellowish wedge-shaped head, its sharp, pointed nose bristling with long whiskers, its pointed teeth, its hairy, brown coat and long scaly tail. When he’s done, he names his cartoon character Maurice Moonrat.

The first episode will feature Maurice Moonrat and his sidekick, Lars, a dull-witted tomcat, bobsledding in the Olympics. The cartoonist wants as much realism as possible, so he talks his studio into sending him to Lake Placid to watch real bobsledders in action. Once at the bobsled run, however, he insists on strapping the moonrat to the front of the bobsled to gauge the rodent’s reaction. The perplexed bobsledders reluctantly agree.

After the run, at the bottom of the hill, the cartoonist unstraps his moonrat, who takes a few shaky steps and curls up in a shivering mass of fur. The bobsledders understand just how cruel and sadistic the cartoonist really is when he insists the moonrat be strapped to the bobsled for a second run. There’s a second run, all right, but it isn’t anything like the cartoonist expected.

By the time they’re all reassembled at the top of the hill, there’s the beginning of a conversion to animation. Maurice Moonrat and Lars are the bobsledders, wearing helmets and sleek uniforms, Maurice the driver, Lars the brakeman, and the cartoonist is tied to the back of the bobsled, to be dragged down the track behind them. Maurice and Lars push off, running at record speed and then hop in the bobsled as they start their decent. Maurice’s pointed teeth break into a wide grin when he hears a long, drawn-out scream from his creator.

Between C and D: New Writing from the Lower East Side Fiction Magazine by Catherine Texier, Joel Rose

My review is a tribute to the twenty-five authors included in this collection whose writing is a rebellion against main stream, conventional American fiction. As Joel Rose and Catherine Texier, editors of Between C & D, the Lower East Side magazine that originally published each of these short stories stated in the book's introduction, their magazine gave writers on the fringe a forum, writers who were inspired by the likes of Genet, Burroughs, Céline, Barthes, Foucault and Henry Miller rather then Updike, Cheever, Carver or Joyce Carol Oats. Their stories are frequently gritty, urban, ironic, sexy, violent, deadpan and sometimes whacky, offbeat and out-and-out strange.

This Penguin edition was published back in 1988. Authors included are David Wojnarowicz, Lisa Blaushild, Rick Henry, Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper, Catherine Texier, Peter Cherches, Susan Daitch, Darius James, Tama Janowitz, Gary Indiana, Lee Eiferman, Reinaldo Povod, Joan Harvey, Don Skiles, Lynne Tillman, Barry Yourgrau, Roberta Allen, Patrick McGrath, Craig Gholson, John Farris, Ron Kolm, Emily Carter, Bruce Benderson and Joel Rose. Chances are nearly all of these names are unfamiliar to anyone reading this review. And for good reason. It has been nearly thirty years and all of these authors have retained their fresh, original vision rather than conforming to any established status quo.

Initially I planned to offer my own critique but, on further reflection, in keeping with each author's singular personality and unique literary voice, I think it more appropriate to include a number of author photos with quotes from their story:

Kathy Acker - "As long as I can remember wanting, I have wanted to slaughter other humans and to watch the emerging of their blood." from Male

Gary Indiana - "That night I fucked Candy Jones for something like three hours. My nuts ached the whole next day and I couldn't get her out of my mind." from I Am Candy Jones

Lynne Tillman - "Sex is important but like anything that's important, it does or causes trouble. Arthur didn't watch television, he watched me. People thought of us like a punchline to a dirty joke." from Dead Talk

Darius James - "The Maid is a monstrous manny-sized cookie jar with doughy animal features and crazed incandescent eyes. Her nappy bleached-blonde Afro is a crown of spiky thorns matted with sweat and splashed with large leaf-like patches of missing melanin." from Negrophobia

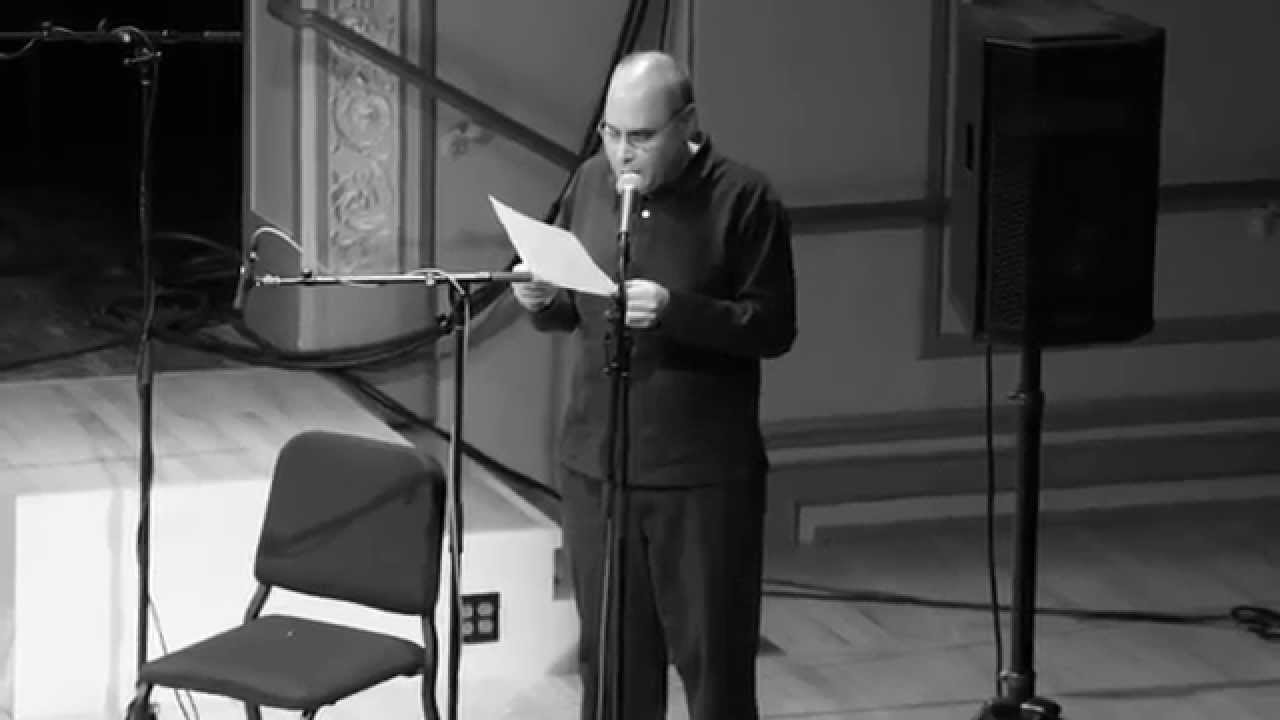

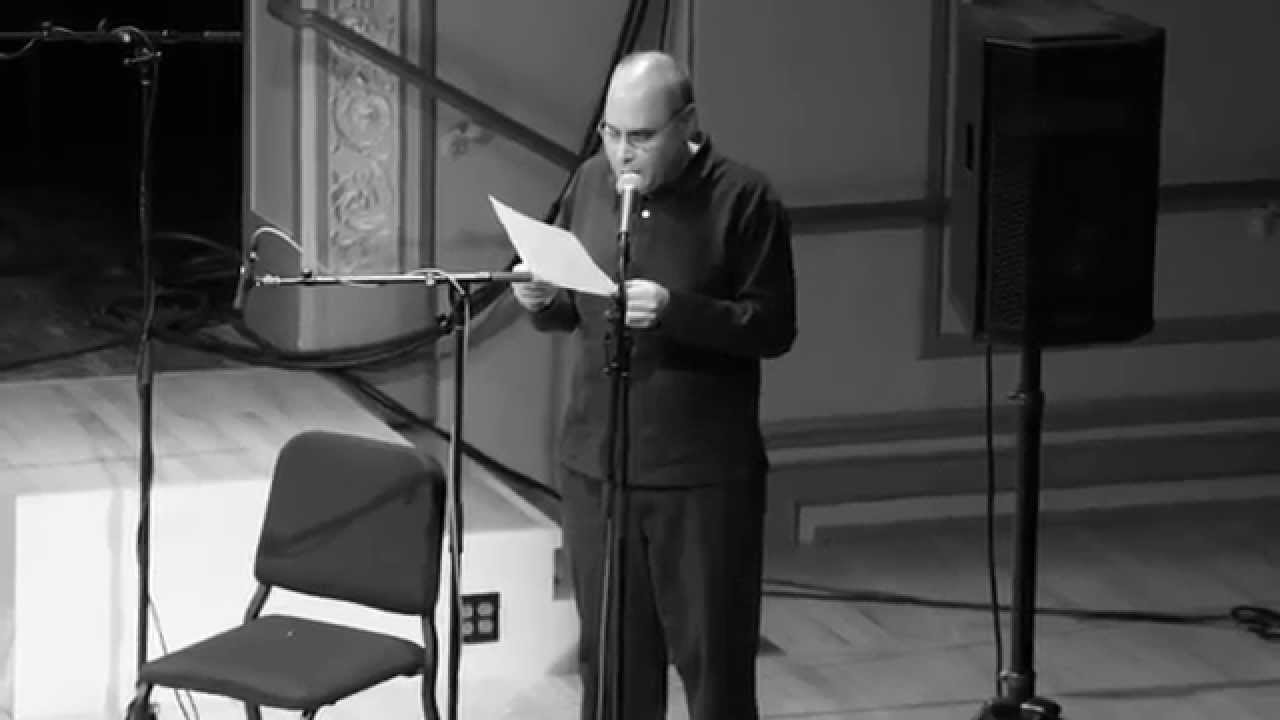

Ron Kolm next to one of his avid readers - "Duke and Jill do drugs. They live on the corner of Avenue A and 10th Street, in a mostly burnt-out building. Bad things keep happening to them. Their best friend, a junkie, rents a truck from a company on Lafayette Street, backs it up over the curb, kicks in their apartment door, and takes all their stuff." from Duke & Jill

Peter Cherches -"Your windows are dirty," she said to him. "It's not my windows," he replied. "It's the world outside." from Dirty Windows

Catherine Texier - "Jimmy is standing a few feet away from me, playing with his knife, testing its sharpness with the palm of his hand, He paces back and forth, his tension rising every time he turns around. I'll get them, he says. I'll get the fuckers." from The Fedora

Dennis Cooper - "He stood on the sidewalk and stuck out his thumb. A trucker chose him. The guy seemed friendly enough, but he kept asking personal questions. "Do you have a girlfriend?" he leered at one point. "Look. I'm on acid, so leave me along, all right?" That shut him up. George hallucinated in peace." from George: Wednesday, Thursday, Friday

5.0

My review is a tribute to the twenty-five authors included in this collection whose writing is a rebellion against main stream, conventional American fiction. As Joel Rose and Catherine Texier, editors of Between C & D, the Lower East Side magazine that originally published each of these short stories stated in the book's introduction, their magazine gave writers on the fringe a forum, writers who were inspired by the likes of Genet, Burroughs, Céline, Barthes, Foucault and Henry Miller rather then Updike, Cheever, Carver or Joyce Carol Oats. Their stories are frequently gritty, urban, ironic, sexy, violent, deadpan and sometimes whacky, offbeat and out-and-out strange.

This Penguin edition was published back in 1988. Authors included are David Wojnarowicz, Lisa Blaushild, Rick Henry, Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper, Catherine Texier, Peter Cherches, Susan Daitch, Darius James, Tama Janowitz, Gary Indiana, Lee Eiferman, Reinaldo Povod, Joan Harvey, Don Skiles, Lynne Tillman, Barry Yourgrau, Roberta Allen, Patrick McGrath, Craig Gholson, John Farris, Ron Kolm, Emily Carter, Bruce Benderson and Joel Rose. Chances are nearly all of these names are unfamiliar to anyone reading this review. And for good reason. It has been nearly thirty years and all of these authors have retained their fresh, original vision rather than conforming to any established status quo.

Initially I planned to offer my own critique but, on further reflection, in keeping with each author's singular personality and unique literary voice, I think it more appropriate to include a number of author photos with quotes from their story:

Kathy Acker - "As long as I can remember wanting, I have wanted to slaughter other humans and to watch the emerging of their blood." from Male

Gary Indiana - "That night I fucked Candy Jones for something like three hours. My nuts ached the whole next day and I couldn't get her out of my mind." from I Am Candy Jones

Lynne Tillman - "Sex is important but like anything that's important, it does or causes trouble. Arthur didn't watch television, he watched me. People thought of us like a punchline to a dirty joke." from Dead Talk

Darius James - "The Maid is a monstrous manny-sized cookie jar with doughy animal features and crazed incandescent eyes. Her nappy bleached-blonde Afro is a crown of spiky thorns matted with sweat and splashed with large leaf-like patches of missing melanin." from Negrophobia

Ron Kolm next to one of his avid readers - "Duke and Jill do drugs. They live on the corner of Avenue A and 10th Street, in a mostly burnt-out building. Bad things keep happening to them. Their best friend, a junkie, rents a truck from a company on Lafayette Street, backs it up over the curb, kicks in their apartment door, and takes all their stuff." from Duke & Jill

Peter Cherches -"Your windows are dirty," she said to him. "It's not my windows," he replied. "It's the world outside." from Dirty Windows

Catherine Texier - "Jimmy is standing a few feet away from me, playing with his knife, testing its sharpness with the palm of his hand, He paces back and forth, his tension rising every time he turns around. I'll get them, he says. I'll get the fuckers." from The Fedora

Dennis Cooper - "He stood on the sidewalk and stuck out his thumb. A trucker chose him. The guy seemed friendly enough, but he kept asking personal questions. "Do you have a girlfriend?" he leered at one point. "Look. I'm on acid, so leave me along, all right?" That shut him up. George hallucinated in peace." from George: Wednesday, Thursday, Friday

A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century by Barbara W. Tuchman

A Distant Mirrorr by Barbara W. Tuchman is, on one level, a seven hundred page encyclopedia of the 14th century’s political, military, religious, social, cultural and economic history. Since Ms. Tuchman is a first-rate writer, on still another level, the book is a compelling, personalized account of individual men and women living through these turbulent, disastrous times, especially one Enguerrand de Coucy V11 (1340-1397), a high-ranking noble, heralded as “the most experienced and skillful of all the knights of France”. The focus on Lord Coucy is supremely appropriate since this nobleman repeatedly pops up as a prime player in many of the century’s key events.

The 14th century witnessed ongoing devastation, including the little ice age, the hundred years’ war, the papal schism, the peasant’s revolt and, most dramatically, the black death of 1348-1350, which depopulated Europe by as much as half. Ms. Tuchman’s book covers it all in twenty-seven chapters, chapter with such headings as Decapitated France: The Bourgeois Rising and the Jacquerie, The Papal Schism, The Worms of the Earth Against the Lions and Dance Macabre.

Many pages are filled with the color and morbidity of the times. By way of example, here is one memorable happening where the French Queen gave a masquerade to celebrate the wedding of a twice widowed lady-in-waiting: six young noblemen, including the King who recently recovered from a bout of madness, disguised themselves as wood savages and entered the masked ball making lewd gestures and howling like wolves as they paraded and capered in the middle of the revelers. When one of the noble spectators came too close with his torch, a spark fell and a few moments later the wood savages, with the exception of the King, were engulfed in flames. Afterwards, the French populace was horrified by this ghastly tragedy, a perverse playing on the edge of madness and death nearly killing their King.

And here is what the author has to say about the young man who concocted the wood savage idea, “The deviser of the affair “cruelest and most insolent of men,” was one Huguet de Guisay, favored in the royal circle for his outrageous schemes. He was a man of “wicked life” who “corrupted and schooled youth in debaucheries,” and held commoners and the poor in hatred and contempt. He called them dogs, and with blows of sword and whip took pleasure in forcing them to imitate barking. If a servant displeased him, he would force the man to lie on the ground and, standing on his back, would kick him with spurs, crying, “Bark, dog!” in response to his cries of pain.” All of the chapters are chock full with such sadistic and violent sketches.

Speaking of the populate, there is plenty of detail on the habits and round of daily life of the common people. And, of course, there is a plethora of detail on the lives of the upper classes. Here is a snippet of one description: “In the evening minstrels played with lutes and harps, reed pipes, bagpipes, trumpets, kettle drums, and cymbals. In the blossoming of secular music as an art in the 14th century, as many as thirty-six different instruments had come into use. If no concert or performance was scheduled after the evening meal, the company entertained each other with song and conversation, tales of the day’s hunting, “graceful questions” on the conventions of live, and verbal games.”

As in any age, it makes for more comfortable living being at the top rather than at the bottom of the social scale. And all those musical instruments speak volumes about how the 14th century was a world away from the plainchant of the early middle ages. In a way, the 14th century musical avant-garde fit in well with the fashions of the times: extravagant headdresses, multicolored, bejeweled jackets and long pointed shoes. For those who had the florins, overindulgence was all the rage.

Ms. Tuchman offers ongoing commentary: for example, regarding military engagement, she cites how the 14th century nobility was too wedded to the idea of glory and riding horses on the battlefield to be effective against the new technology of the long-bow and foot soldiers with pikes. And here is a general, overarching comment about the age, “The times were not static. Loss of confidence in the guarantors of order opened the way to demands for change, and miseria gave force to the impulse. The oppressed were no longer enduring but rebelling, although, like the bourgeois who tried to compel reform, they were inadequate, unready, and unequipped for the task.” Indeed, reading about 14th century economic upheaval one is reminded of Karl Marx’s scathing observations four hundred years later.

On a personal note, my primary interests are literature and philosophy; I usually do not read history. However, if I were to recommend one history book, this is the book. Why? Because Ms. Tuchman’s work is not only extremely well written and covers many aspects of the period’s art, music, literature, religion and mysticism, but the turbulent, transitional 14th century does truly mirror our modern world. Quite a time to be alive.

5.0

A Distant Mirrorr by Barbara W. Tuchman is, on one level, a seven hundred page encyclopedia of the 14th century’s political, military, religious, social, cultural and economic history. Since Ms. Tuchman is a first-rate writer, on still another level, the book is a compelling, personalized account of individual men and women living through these turbulent, disastrous times, especially one Enguerrand de Coucy V11 (1340-1397), a high-ranking noble, heralded as “the most experienced and skillful of all the knights of France”. The focus on Lord Coucy is supremely appropriate since this nobleman repeatedly pops up as a prime player in many of the century’s key events.

The 14th century witnessed ongoing devastation, including the little ice age, the hundred years’ war, the papal schism, the peasant’s revolt and, most dramatically, the black death of 1348-1350, which depopulated Europe by as much as half. Ms. Tuchman’s book covers it all in twenty-seven chapters, chapter with such headings as Decapitated France: The Bourgeois Rising and the Jacquerie, The Papal Schism, The Worms of the Earth Against the Lions and Dance Macabre.

Many pages are filled with the color and morbidity of the times. By way of example, here is one memorable happening where the French Queen gave a masquerade to celebrate the wedding of a twice widowed lady-in-waiting: six young noblemen, including the King who recently recovered from a bout of madness, disguised themselves as wood savages and entered the masked ball making lewd gestures and howling like wolves as they paraded and capered in the middle of the revelers. When one of the noble spectators came too close with his torch, a spark fell and a few moments later the wood savages, with the exception of the King, were engulfed in flames. Afterwards, the French populace was horrified by this ghastly tragedy, a perverse playing on the edge of madness and death nearly killing their King.

And here is what the author has to say about the young man who concocted the wood savage idea, “The deviser of the affair “cruelest and most insolent of men,” was one Huguet de Guisay, favored in the royal circle for his outrageous schemes. He was a man of “wicked life” who “corrupted and schooled youth in debaucheries,” and held commoners and the poor in hatred and contempt. He called them dogs, and with blows of sword and whip took pleasure in forcing them to imitate barking. If a servant displeased him, he would force the man to lie on the ground and, standing on his back, would kick him with spurs, crying, “Bark, dog!” in response to his cries of pain.” All of the chapters are chock full with such sadistic and violent sketches.

Speaking of the populate, there is plenty of detail on the habits and round of daily life of the common people. And, of course, there is a plethora of detail on the lives of the upper classes. Here is a snippet of one description: “In the evening minstrels played with lutes and harps, reed pipes, bagpipes, trumpets, kettle drums, and cymbals. In the blossoming of secular music as an art in the 14th century, as many as thirty-six different instruments had come into use. If no concert or performance was scheduled after the evening meal, the company entertained each other with song and conversation, tales of the day’s hunting, “graceful questions” on the conventions of live, and verbal games.”

As in any age, it makes for more comfortable living being at the top rather than at the bottom of the social scale. And all those musical instruments speak volumes about how the 14th century was a world away from the plainchant of the early middle ages. In a way, the 14th century musical avant-garde fit in well with the fashions of the times: extravagant headdresses, multicolored, bejeweled jackets and long pointed shoes. For those who had the florins, overindulgence was all the rage.

Ms. Tuchman offers ongoing commentary: for example, regarding military engagement, she cites how the 14th century nobility was too wedded to the idea of glory and riding horses on the battlefield to be effective against the new technology of the long-bow and foot soldiers with pikes. And here is a general, overarching comment about the age, “The times were not static. Loss of confidence in the guarantors of order opened the way to demands for change, and miseria gave force to the impulse. The oppressed were no longer enduring but rebelling, although, like the bourgeois who tried to compel reform, they were inadequate, unready, and unequipped for the task.” Indeed, reading about 14th century economic upheaval one is reminded of Karl Marx’s scathing observations four hundred years later.

On a personal note, my primary interests are literature and philosophy; I usually do not read history. However, if I were to recommend one history book, this is the book. Why? Because Ms. Tuchman’s work is not only extremely well written and covers many aspects of the period’s art, music, literature, religion and mysticism, but the turbulent, transitional 14th century does truly mirror our modern world. Quite a time to be alive.

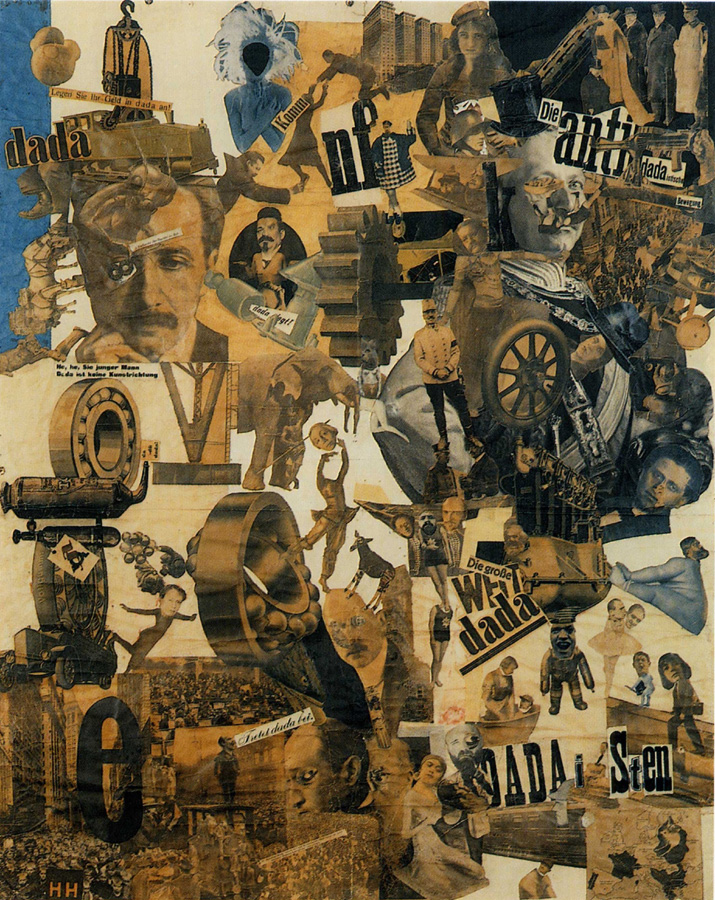

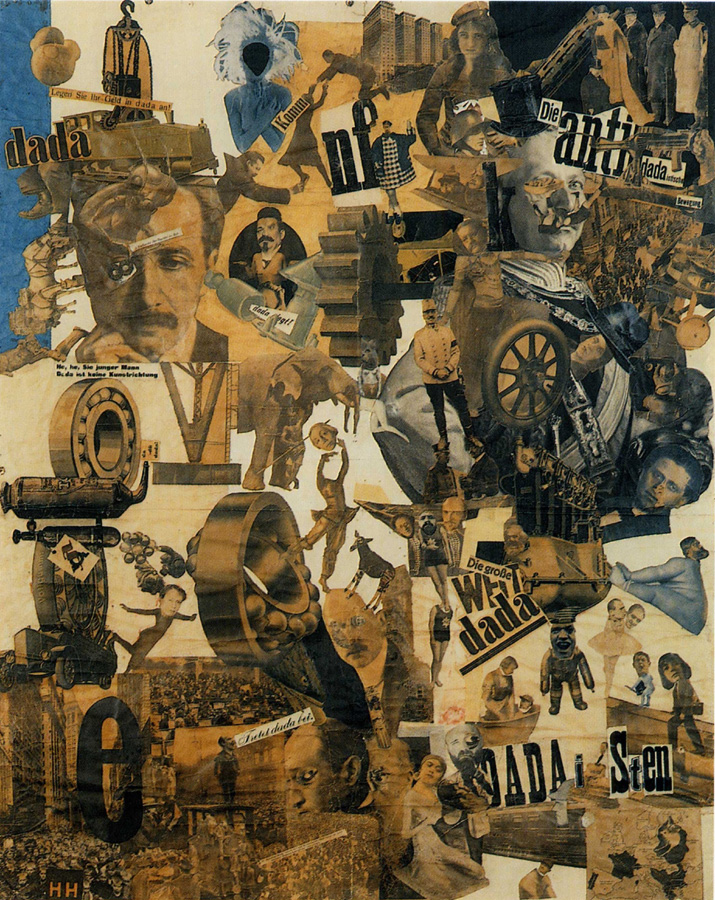

The Photomontages of Hannah Hoch by Hannah H̦ch

One of the leading artists in the Berlin Dada movement during Post-World War I Weimar Republic times, Hannah Höch (1889-1978) was among the most original and creative minds in the world of 20th century art. This book is a comprehensive study covering 50+ years of her experimentation and innovation in constructing photomontages, an art form employing scissors, glue and photo images from magazines and newspapers. Also, much information is provided regarding her life and times, with a particular emphasis of how the artist responded to the place of women within the context of 20th century European culture and society.

In order to provide a glimpse of the richness of Hannah Höch’s photomontages (this book contains more than 100 color plates), I will focus exclusively on one of her most famous works with the many-word title – Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany (1919-1920) 114 x 90 cm. (4 ½ feet x 3 ½ feet). One could write page after page about the Dadaist rendering of people, ideas, and events depicted in this photomontage that slices and dices a society moving through those turbulent 1919-1920 years. Several modest observations: