Scan barcode

glenncolerussell's reviews

1456 reviews

See Jack by Russell Edson

Russell Edson (1935-2014) wrote and published his quizzical, surreal, distinctively Russell Edson-like prose poems for nearly fifty years. Reading one of his collections published back in the 50s, 60s, 70s or 80s you might think Russell would run out of ideas for these curious mustachioed eggs, but not so - right through his ripe old age he could, like a farmer’s prize hen, still keep laying his eggs.

And since his prose poems are half-pagers or one-pagers, nothing better than offering a sample for a taste test: below are several of the shortest from this collection, his last published book. Oh, Russell was also an illustrator and artist – Russell did the cover art for See Jack. Here you go:

AFTER THE CONCERT

After the concert the cellist takes his cello home and gets into bed with it.

He knows if his fellow musicians knew what he did at night with a cello old enough to be his great grandmother, they’d report him to the Humane Society.

But they don’t know, he thinks as he falls asleep, his face buried in the cello’s ancient bosom.

THE CONVERSATION

There was a woman whose face was a cow’s milk bag, a pink pouch with four dugs pointing out of it . . .

A man with a little three-legged milking stool comes. She stoops and he begins to milk her face . . .

A MAN WHO WENT FOR A WALK

There was a man who attached a collar and leash to his neck. And, holding the leash in one hand, took himself for a walk, lifting his leg every so often to mark his way.

MYOPIA

He had only one eye. In the other socket was a belly button.

Oh, but not to worry, in his umbilical depression was his other eye fully equipped with eyelid and lashes. It even had tears for sad stories and onions.

But because his belly button, I mean his umbilical eye, was nearsighted, it wore a monocle ground for distant viewing.

He would stand at a window at night letting his belly button, I mean, his umbilical eye, view the moon as it flowed through the monocle into his belly button, I mean, his umbilical eye . . .

PORTRAIT OF A REALIST

There is an old man who pukes metal. Today bedsprings. Yesterday, the iron maiden of Nuremberg.

His wife is more for cloth. Today she pukes used mummy wrappings. Yesterday a teddy bear without a head.

Suddenly the old man pukes a battalion of lead soldiers. He wife upchucks a bundle of soiled diapers.

They have a son who’s also a puker. But, unlike his parents, he pukes real puke . . .

WAITING FOR THE FAT LADY TO SING

It was the longest opera ever written. By the time the fat lady sang most of the audience had died in their seats still holding their programs, the theater full of flies and microbes.

Some began to think that perhaps the opera was a bit long, that maybe the fat lady should start singing a little earlier so the audience might have time to write their wills, and to say goodbye to friends and family.

But the others felt, what better way to die than waiting for the fat lady to sing in the make-believe of theater, where nothing’s real, not the fat lady, nor even death . . .

------

Russell inspired me to write my own prose poems. Keeping with Russell’s themes above, here are a couple I wrote some time ago:

THE TIGHTROPE WALKER

Will the tightrope walker fall? Who can tell? Her torso and legs display an uncanny sense of balance. Nevertheless, there are some significant deterrents. Like the rolling pin she’s holding, the jumbo spheres with geometrical inscriptions squatting next to the net, an, oh yes . . . one end of the tightrope is fastened around her ankle.

THE THROW-UP CLUB

By a stroke of luck, my application for membership was accepted by the throw-up club. As a full-fledged member, I was allowed to join the club’s next meeting way out in the woods.

Once alone in the woods, all the members of the throw-up club could throw-up in peace. Starting in the morning and continuing until late afternoon, members took turns throwing up. After dinner, having that overly full and crapulous feeling, the throw-up club has a sing-along. Some members threw up before the songs, other members threw up after the songs, but all the members, including myself, observed restraint and proper decorum by not once throwing up during the songs.

5.0

Russell Edson (1935-2014) wrote and published his quizzical, surreal, distinctively Russell Edson-like prose poems for nearly fifty years. Reading one of his collections published back in the 50s, 60s, 70s or 80s you might think Russell would run out of ideas for these curious mustachioed eggs, but not so - right through his ripe old age he could, like a farmer’s prize hen, still keep laying his eggs.

And since his prose poems are half-pagers or one-pagers, nothing better than offering a sample for a taste test: below are several of the shortest from this collection, his last published book. Oh, Russell was also an illustrator and artist – Russell did the cover art for See Jack. Here you go:

AFTER THE CONCERT

After the concert the cellist takes his cello home and gets into bed with it.

He knows if his fellow musicians knew what he did at night with a cello old enough to be his great grandmother, they’d report him to the Humane Society.

But they don’t know, he thinks as he falls asleep, his face buried in the cello’s ancient bosom.

THE CONVERSATION

There was a woman whose face was a cow’s milk bag, a pink pouch with four dugs pointing out of it . . .

A man with a little three-legged milking stool comes. She stoops and he begins to milk her face . . .

A MAN WHO WENT FOR A WALK

There was a man who attached a collar and leash to his neck. And, holding the leash in one hand, took himself for a walk, lifting his leg every so often to mark his way.

MYOPIA

He had only one eye. In the other socket was a belly button.

Oh, but not to worry, in his umbilical depression was his other eye fully equipped with eyelid and lashes. It even had tears for sad stories and onions.

But because his belly button, I mean his umbilical eye, was nearsighted, it wore a monocle ground for distant viewing.

He would stand at a window at night letting his belly button, I mean, his umbilical eye, view the moon as it flowed through the monocle into his belly button, I mean, his umbilical eye . . .

PORTRAIT OF A REALIST

There is an old man who pukes metal. Today bedsprings. Yesterday, the iron maiden of Nuremberg.

His wife is more for cloth. Today she pukes used mummy wrappings. Yesterday a teddy bear without a head.

Suddenly the old man pukes a battalion of lead soldiers. He wife upchucks a bundle of soiled diapers.

They have a son who’s also a puker. But, unlike his parents, he pukes real puke . . .

WAITING FOR THE FAT LADY TO SING

It was the longest opera ever written. By the time the fat lady sang most of the audience had died in their seats still holding their programs, the theater full of flies and microbes.

Some began to think that perhaps the opera was a bit long, that maybe the fat lady should start singing a little earlier so the audience might have time to write their wills, and to say goodbye to friends and family.

But the others felt, what better way to die than waiting for the fat lady to sing in the make-believe of theater, where nothing’s real, not the fat lady, nor even death . . .

------

Russell inspired me to write my own prose poems. Keeping with Russell’s themes above, here are a couple I wrote some time ago:

THE TIGHTROPE WALKER

Will the tightrope walker fall? Who can tell? Her torso and legs display an uncanny sense of balance. Nevertheless, there are some significant deterrents. Like the rolling pin she’s holding, the jumbo spheres with geometrical inscriptions squatting next to the net, an, oh yes . . . one end of the tightrope is fastened around her ankle.

THE THROW-UP CLUB

By a stroke of luck, my application for membership was accepted by the throw-up club. As a full-fledged member, I was allowed to join the club’s next meeting way out in the woods.

Once alone in the woods, all the members of the throw-up club could throw-up in peace. Starting in the morning and continuing until late afternoon, members took turns throwing up. After dinner, having that overly full and crapulous feeling, the throw-up club has a sing-along. Some members threw up before the songs, other members threw up after the songs, but all the members, including myself, observed restraint and proper decorum by not once throwing up during the songs.

The Inferno (Hell) by Henri Barbusse

The Inferno (alternate title - Hell) by Henri Barbusse makes for one strange reading experience. We have our first-person narrator, a thirty-year-old gent who takes up residence in a Paris rooming house only to discover a crack in the wall where he can remain undetected as he observes the happenings in the next room.

Then there’s the dialogue and action of the various occupants of that next room who come and go, all filtered through the alembic of the voyeuristic narrator. And what intriguing characters they are, acting out the drama of their lives under the voyeur’s watchful eye. Among others, two preadolescent fledgling lovers; a sentimental romantic and her tall mustachioed, stiff, jaundiced heartthrob; a pregnant young woman tending to a dying old poet who is her lover.

What exactly is it about being a voyeur? We all have had the legitimate experience of being watchers of films and plays and readers of books full to the brim with comedy and drama of character's lives but what of observing real people in real situations?

Yet to be a viewer unbeknownst to those being viewed living their "real" lives is something else again, quite different from books or movies. The enchantment of this short novel provides us an opportunity to join the young voyeur as he peeps through a crack into the next room.

Does reading a story told by voyeur make us voyeurs? Certainly not, but then again, there is something about partaking in the voyeur’s peeping. By way of example, here is a snatch of dialogue from the next room:

“I love you so much,” he said simply.

“Ah,” she answered, “you will not die!”

“Think of all you have done for me!” she exclaimed, clasping her hands and bending her magnificent body toward him, as if prostrating herself before him.

Then the voyeur/narrator observes: You could tell that they were speaking open-heartedly. What a good thing it is to be frank and speak without reticence, without the shame and guilt of not knowing what one is saying and for each to go straight to the other. It is almost a miracle.

Thus, we as readers are given two separate dramas: the participants in the next room in their various combinations and also the life of the young voyeur - his emotional response, his philosophical reflections on his own life and on the lives of those he observes.

And perhaps that’s not such a bad thing after all, the author providing us with an alternate rhythm of observing the next room and the mind of the voyeur, squeezing the novel as art form with such a unique twist. Ah, the French! Toward the end of his stay at the rooming house, we read:

"I wanted to know the secret of life. I had seen men, groups, deeds, faces. In the twilight I had seen the tremulous eyes of beings as deep as wells. I had seen the mouth that said in a burst of glory, "I am more sensitive than others." I had seen the struggle to love and make one's self understood, the refusal of two persons in conversation to give themselves to each other, the coming together of two lovers, the lovers with an infectious smile, who are lovers in name only, who bury themselves in kisses, who press wound to wound to cure themselves, between whom there is really no attachment, and who, in spite of their ecstasy deriving light from shadow, are strangers as much as the sun and mood are strangers."

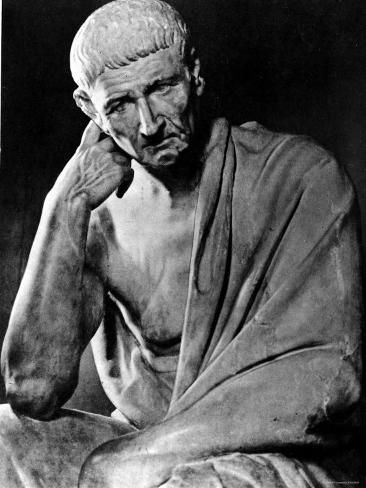

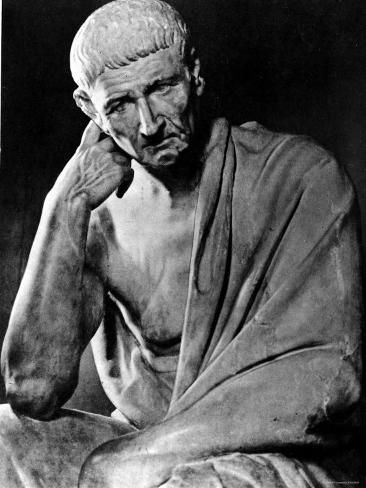

French author Henri Barbusse, 1873-1935

“I believe that around us there is only one word on all sides, one immense word which reveals our solitude and extinguishes our radiance: Nothing! I believe that that word does not point to our insignificance or our unhappiness, but on the contrary to our fulfillment and our divinity, since everything is in ourselves.”

― Henri Barbusse, The Inferno

5.0

The Inferno (alternate title - Hell) by Henri Barbusse makes for one strange reading experience. We have our first-person narrator, a thirty-year-old gent who takes up residence in a Paris rooming house only to discover a crack in the wall where he can remain undetected as he observes the happenings in the next room.

Then there’s the dialogue and action of the various occupants of that next room who come and go, all filtered through the alembic of the voyeuristic narrator. And what intriguing characters they are, acting out the drama of their lives under the voyeur’s watchful eye. Among others, two preadolescent fledgling lovers; a sentimental romantic and her tall mustachioed, stiff, jaundiced heartthrob; a pregnant young woman tending to a dying old poet who is her lover.

What exactly is it about being a voyeur? We all have had the legitimate experience of being watchers of films and plays and readers of books full to the brim with comedy and drama of character's lives but what of observing real people in real situations?

Yet to be a viewer unbeknownst to those being viewed living their "real" lives is something else again, quite different from books or movies. The enchantment of this short novel provides us an opportunity to join the young voyeur as he peeps through a crack into the next room.

Does reading a story told by voyeur make us voyeurs? Certainly not, but then again, there is something about partaking in the voyeur’s peeping. By way of example, here is a snatch of dialogue from the next room:

“I love you so much,” he said simply.

“Ah,” she answered, “you will not die!”

“Think of all you have done for me!” she exclaimed, clasping her hands and bending her magnificent body toward him, as if prostrating herself before him.

Then the voyeur/narrator observes: You could tell that they were speaking open-heartedly. What a good thing it is to be frank and speak without reticence, without the shame and guilt of not knowing what one is saying and for each to go straight to the other. It is almost a miracle.

Thus, we as readers are given two separate dramas: the participants in the next room in their various combinations and also the life of the young voyeur - his emotional response, his philosophical reflections on his own life and on the lives of those he observes.

And perhaps that’s not such a bad thing after all, the author providing us with an alternate rhythm of observing the next room and the mind of the voyeur, squeezing the novel as art form with such a unique twist. Ah, the French! Toward the end of his stay at the rooming house, we read:

"I wanted to know the secret of life. I had seen men, groups, deeds, faces. In the twilight I had seen the tremulous eyes of beings as deep as wells. I had seen the mouth that said in a burst of glory, "I am more sensitive than others." I had seen the struggle to love and make one's self understood, the refusal of two persons in conversation to give themselves to each other, the coming together of two lovers, the lovers with an infectious smile, who are lovers in name only, who bury themselves in kisses, who press wound to wound to cure themselves, between whom there is really no attachment, and who, in spite of their ecstasy deriving light from shadow, are strangers as much as the sun and mood are strangers."

French author Henri Barbusse, 1873-1935

“I believe that around us there is only one word on all sides, one immense word which reveals our solitude and extinguishes our radiance: Nothing! I believe that that word does not point to our insignificance or our unhappiness, but on the contrary to our fulfillment and our divinity, since everything is in ourselves.”

― Henri Barbusse, The Inferno

Morphine by Mikhail Bulgakov

First published in 1925, Morphine is a mini-novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, one of the giants of twenteith century Russian literature. The storyline is simple: Bromgard, a young doctor moves from the backwoods to a small country town to practice medicine in a clinic. A month passes and he receives news that Polyakov, a friend, a "very reasonable man," he knew as a student in medical school is ill and needs his help.

Bromgard plans to travel by train to his friend but before his scheduled departure Polyakov is brought to the clinic on the verge of death, resulting from a self-inflicted bullet wound. But before Polyakov dies, he hands Dr. Bromgard a diary recording his addiction to morphine. And the heart and soul of this Bulgakov tale is the contents of the diary.

Such a simple story. But please don't be fooled - through Bulgakov's literary magic we are given a gem. The author crafts with a kind of subtle perfection the step-by-step decent of an intelligent young man with a promising future in the grip of morphine addiction.

And it all starts so innocently: On the night of February 15th an otherwise perfectly healthy twenty-three year old Dr. Poyakov experiences intense stomach pain. He sends for Anna Kirillovna, a kind and intellegent nurse, and she gives him a morphine injection.

The next day, Dr. Polyakov makes a decision that will prove to be a drastic mistake, turning him into an addict. We read, "Fearing a recurrence of yesterday's attack, I injected myself in the thigh with one centigramme"

Such a penetrating observation on human psychology: the young doctor does not experience intense pain; rather, he gives himself a morphine injection because he fears intense pain. Oh my goodness: according to the wisdom of ancient Greek philosophers, a prime emotion we must overcome is our fear, most especially fear of pain and fear of death. And ff we act based solely on our fear, the consequences can quite possibly be dreadful in the extreme

A mere two weeks later, the young doctor's identity has completely transformed; he and his morphine are one. Here are his words from the diary: "I would say that a man can only work normally after an injection of morphine."

Then, we read the following March 10 entry: "Never before have I had such dreams at dawn. They are double dreams. The main one, I would say, is made of glass. It is transparent. This is what happened: I see a lighted lamp, fearfully bright, from which blazes a stream of many-colored light. Amneris, swaying like a green feather, is singing. An unearthly orchestra is playing with a full, rich sound - although I cannot really convey this in words. In short, in a normal dream music is soundless . . . but in my dream the music sounds, quite heavenly. And best of all I can make the music louder or softer at will."

Ecstasy! Ecstasy! Ecstasy! Our young doctor is completely hooked, psychologically every bit as much as physically. Incidentally, Amneris is an opera singer, the doctor's former mistress who left him weeks prior to his first morphine injection.

But such ethereal, blissful dreams have a price, a big price. On April 9th he writes, "The devil is in this phial. . . . This is the effect: on injecting one syringe of a 2% solution, you feel almost immediately a state of calm, which quickly grows into a delightful euphoria. This lasts for only a minute or two, then it vanishes without a trace as though it has never been. Then comes pain, horror, darkness."

And then a month later we read: "What overtakes the addict deprived of morphine for a mere hour or two is not a "depressed condition": it is slow death."

Ten more months of morphine addiction, alternating between injections and the slow death between injections, Dr. Polyakov takes his own life at tender age of twenty-four. Such a tragedy.

From what I've read on the net, this is a much read and consulted cautionary tale for those involved in the medical industry. And recognizing the many forms of drug addiction in our brave new twenty-first century world, Bulgakov's Morphine is a cautionary tale for each and every one of us.

5.0

First published in 1925, Morphine is a mini-novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, one of the giants of twenteith century Russian literature. The storyline is simple: Bromgard, a young doctor moves from the backwoods to a small country town to practice medicine in a clinic. A month passes and he receives news that Polyakov, a friend, a "very reasonable man," he knew as a student in medical school is ill and needs his help.

Bromgard plans to travel by train to his friend but before his scheduled departure Polyakov is brought to the clinic on the verge of death, resulting from a self-inflicted bullet wound. But before Polyakov dies, he hands Dr. Bromgard a diary recording his addiction to morphine. And the heart and soul of this Bulgakov tale is the contents of the diary.

Such a simple story. But please don't be fooled - through Bulgakov's literary magic we are given a gem. The author crafts with a kind of subtle perfection the step-by-step decent of an intelligent young man with a promising future in the grip of morphine addiction.

And it all starts so innocently: On the night of February 15th an otherwise perfectly healthy twenty-three year old Dr. Poyakov experiences intense stomach pain. He sends for Anna Kirillovna, a kind and intellegent nurse, and she gives him a morphine injection.

The next day, Dr. Polyakov makes a decision that will prove to be a drastic mistake, turning him into an addict. We read, "Fearing a recurrence of yesterday's attack, I injected myself in the thigh with one centigramme"

Such a penetrating observation on human psychology: the young doctor does not experience intense pain; rather, he gives himself a morphine injection because he fears intense pain. Oh my goodness: according to the wisdom of ancient Greek philosophers, a prime emotion we must overcome is our fear, most especially fear of pain and fear of death. And ff we act based solely on our fear, the consequences can quite possibly be dreadful in the extreme

A mere two weeks later, the young doctor's identity has completely transformed; he and his morphine are one. Here are his words from the diary: "I would say that a man can only work normally after an injection of morphine."

Then, we read the following March 10 entry: "Never before have I had such dreams at dawn. They are double dreams. The main one, I would say, is made of glass. It is transparent. This is what happened: I see a lighted lamp, fearfully bright, from which blazes a stream of many-colored light. Amneris, swaying like a green feather, is singing. An unearthly orchestra is playing with a full, rich sound - although I cannot really convey this in words. In short, in a normal dream music is soundless . . . but in my dream the music sounds, quite heavenly. And best of all I can make the music louder or softer at will."

Ecstasy! Ecstasy! Ecstasy! Our young doctor is completely hooked, psychologically every bit as much as physically. Incidentally, Amneris is an opera singer, the doctor's former mistress who left him weeks prior to his first morphine injection.

But such ethereal, blissful dreams have a price, a big price. On April 9th he writes, "The devil is in this phial. . . . This is the effect: on injecting one syringe of a 2% solution, you feel almost immediately a state of calm, which quickly grows into a delightful euphoria. This lasts for only a minute or two, then it vanishes without a trace as though it has never been. Then comes pain, horror, darkness."

And then a month later we read: "What overtakes the addict deprived of morphine for a mere hour or two is not a "depressed condition": it is slow death."

Ten more months of morphine addiction, alternating between injections and the slow death between injections, Dr. Polyakov takes his own life at tender age of twenty-four. Such a tragedy.

From what I've read on the net, this is a much read and consulted cautionary tale for those involved in the medical industry. And recognizing the many forms of drug addiction in our brave new twenty-first century world, Bulgakov's Morphine is a cautionary tale for each and every one of us.

Notes from Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Dostoevsky leads us into the deepest recesses of human consciousness, a mire of stinky sewers, feted pits and foul-smelling rat holes - novel as existential torment and alienation.

Do you envision a utopia founded on the principals of love and universal brotherhood? If so, beware the underground man. And what is it about the underground? Well, ladies and gentlemen, here are several quotes from the text with my comments:

"I would now like to tell you, gentlemen, whether you do or do not wish to hear it, why I never managed to become even an insect. I'll tell you solemnly that I wanted many times to become an insect."----------The underground man's opening reflections form the first part of this short novel. He is forty years old, sits in his apartment, arms folded, brooding about life and death, telling us all about his underbelly-ish plight as a man-mouse, speaking about the subject giving him the greatest pleasure: himself.

"If man has not become more bloodthirsty from civilization, at any rate he has certainly become bloodthirsty in a worse, a viler way than formerly.” ----------The underground man spews out his view of others. If all humankind were to succumb to plague and die a horrible, anguished death, we can see in our mind's eye the underground man chuckling to himself and thinking every single minute of the excruciating pain of all those millions of men and women and children were well deserved. But, in all fairness, the underground man tells us he has a sensitive streak, being as insecure and touchy as a hunchback or dwarf.

"Two times two is four has a cocky look; it stands across your path, arms akimbo, and spits. I agree that two times two is four is an excellent thing; but if we're going to start praising everything, then two times two is five is sometimes also a most charming little thing."----------The underground man despises nature and the laws of nature. One can imagine how he would react if someone spoke of the philosophy of harmony or compassion – squinting his eyes, grinding his teeth and clenching his fists so hard blood would appear on his palms.

"Of Simonov's two guests, one was Ferfichkin, from Russian-German stock- short, monkey-faced, a fool who comically mimicked everyone, my bitterest enemy even in the lower grades--a mean, impudent little fanfaron who played at being most ticklish ambitious, though of course he was a coward at heart." ----------Here we have the underground man's reflections on encountering someone from his boyhood past. If you think the underground man would have less flattering things to say about you if he saw you talking in a railway station or eating at a restaurant, please continue reading. The underground man's hatred and bitterness reaches a high pitch by simply being around three of his former acquaintances. Has there ever been a more comical and compelling scene in all of literature?

"That night I had the most hideous dreams. No wonder: all evening I was oppressed by recollections of the penal servitude of my school years, and I could not get rid of them. I had been tucked away in that school by distant relations whose dependent I was and of whom I had no notion thereafter - tucked away, orphaned, already beaten down by their reproaches, already pensive, taciturn, gazing wildly about at everything. My schoolfellows met me with spiteful and merciless derision, because I was not like any of them. . . . I immediately began to hate them, and shut myself away from everyone in timorous, wounded, and inordinate pride."----------The underground man deals with a cab driver, a young prostitute and his servant. Such nastiness, such viciousness -- every single encounter vivid and memorable. Dostoyevsky at his finest.

"We're stillborn, and have long ceased to be born of living fathers, and we like this more and more. We're acquiring a taste for it. Soon we'll contrive to be born somehow from an idea. But enough; I don't want to write any more "from Underground" . . . "----------You may forget other works of literature you have read; however, I can assure you, once you have read the underground man's notes it will be an experience you will not soon forget.

5.0

Dostoevsky leads us into the deepest recesses of human consciousness, a mire of stinky sewers, feted pits and foul-smelling rat holes - novel as existential torment and alienation.

Do you envision a utopia founded on the principals of love and universal brotherhood? If so, beware the underground man. And what is it about the underground? Well, ladies and gentlemen, here are several quotes from the text with my comments:

"I would now like to tell you, gentlemen, whether you do or do not wish to hear it, why I never managed to become even an insect. I'll tell you solemnly that I wanted many times to become an insect."----------The underground man's opening reflections form the first part of this short novel. He is forty years old, sits in his apartment, arms folded, brooding about life and death, telling us all about his underbelly-ish plight as a man-mouse, speaking about the subject giving him the greatest pleasure: himself.

"If man has not become more bloodthirsty from civilization, at any rate he has certainly become bloodthirsty in a worse, a viler way than formerly.” ----------The underground man spews out his view of others. If all humankind were to succumb to plague and die a horrible, anguished death, we can see in our mind's eye the underground man chuckling to himself and thinking every single minute of the excruciating pain of all those millions of men and women and children were well deserved. But, in all fairness, the underground man tells us he has a sensitive streak, being as insecure and touchy as a hunchback or dwarf.

"Two times two is four has a cocky look; it stands across your path, arms akimbo, and spits. I agree that two times two is four is an excellent thing; but if we're going to start praising everything, then two times two is five is sometimes also a most charming little thing."----------The underground man despises nature and the laws of nature. One can imagine how he would react if someone spoke of the philosophy of harmony or compassion – squinting his eyes, grinding his teeth and clenching his fists so hard blood would appear on his palms.

"Of Simonov's two guests, one was Ferfichkin, from Russian-German stock- short, monkey-faced, a fool who comically mimicked everyone, my bitterest enemy even in the lower grades--a mean, impudent little fanfaron who played at being most ticklish ambitious, though of course he was a coward at heart." ----------Here we have the underground man's reflections on encountering someone from his boyhood past. If you think the underground man would have less flattering things to say about you if he saw you talking in a railway station or eating at a restaurant, please continue reading. The underground man's hatred and bitterness reaches a high pitch by simply being around three of his former acquaintances. Has there ever been a more comical and compelling scene in all of literature?

"That night I had the most hideous dreams. No wonder: all evening I was oppressed by recollections of the penal servitude of my school years, and I could not get rid of them. I had been tucked away in that school by distant relations whose dependent I was and of whom I had no notion thereafter - tucked away, orphaned, already beaten down by their reproaches, already pensive, taciturn, gazing wildly about at everything. My schoolfellows met me with spiteful and merciless derision, because I was not like any of them. . . . I immediately began to hate them, and shut myself away from everyone in timorous, wounded, and inordinate pride."----------The underground man deals with a cab driver, a young prostitute and his servant. Such nastiness, such viciousness -- every single encounter vivid and memorable. Dostoyevsky at his finest.

"We're stillborn, and have long ceased to be born of living fathers, and we like this more and more. We're acquiring a taste for it. Soon we'll contrive to be born somehow from an idea. But enough; I don't want to write any more "from Underground" . . . "----------You may forget other works of literature you have read; however, I can assure you, once you have read the underground man's notes it will be an experience you will not soon forget.

The Wounded Breakfast by Russell Edson

One literary critic wrote: "The first Russell Edson prose poem I ever read was Counting Sheep. The poem begins: “A scientist has a test tube full of sheep. He wonders if he should try to shrink a pasture for them. // They are like grains of rice.” The poem was written at the same grade-level as USA Today, but it took the top of my head off per Emily Dickinson’s dictum —it moved me as much as any so-called real, immortal art. And, to my amazement, the lines were free from the self-congratulation that Wallace Stevens warned against."

Likewise, this collection of Russell Edson prose poems took the top of my head off. And his work moves me as much as any writing I've ever read. Here are three of my favorites below. Hope you enjoy!

YOU

Out of nothing there comes a time called childhood, which is simply a path leading through an archway called adolescence. A small town there, past the arch called youth.

Soon, down the road, where one almost misses the life lived beyond the flower, is a small shack labeled, you.

And it is here the future lives in the several postures of arm on windowsill, cheek on this elbow on knees, face in the hands; sometimes the head thrown back, eyes staring into the ceiling . . . This into nothing down the long day’s arc . . .

THE WOUNDED BREAKFAST

A huge shoe mounts up from the horizon, squealing and grinding forward on small wheels, even as a man sitting to breakfast on his veranda is suddenly engulfed in a great shadow, almost the size of the night . . .

He looks up and sees a huge shoe ponderously mounting out of the earth.

Up in the unlaced ankle-part an old woman stands at a helm behind the great tongue curled forward; the thick laces dragging like ships' rope on the ground as the huge thing squeals and grinds forward; children everywhere, they look from the shoelace holes, they crowd about the old woman, even as she pilots this huge shoe over the earth . . .

Soon the huge shoe is descending the opposite horizon, a monstrous snail squealing and grinding into the earth . . .

The man turns to his breakfast again, but sees it's been wounded, the yolk of one of his eggs is bleeding . . .

THE RAT'S TIGHT SCHEDULE

A man stumbled on some rat droppings.

Hey, who put those there? That's dangerous, he said.

His wife said, those are pieces of a rat.

Wait, he's coming apart, he's all over the floor, said the husband.

He can't help it; you don't think he wants to drop pieces of himself all over the floor, do you? said the wife.

But I could have flipped and fallen through the floor, said the husband.

Well, he's been thinking of turning into a marsupial, so try to have a little patience. I'm sure if you were thinking of turning into a marsupial he'd be patient with you. But, on the other hand, don't embarrass him if he decides to remain placental, he's on a very tight schedule, said the wife.

A marsupial, a wonderful choice, cried the husband . . .

5.0

One literary critic wrote: "The first Russell Edson prose poem I ever read was Counting Sheep. The poem begins: “A scientist has a test tube full of sheep. He wonders if he should try to shrink a pasture for them. // They are like grains of rice.” The poem was written at the same grade-level as USA Today, but it took the top of my head off per Emily Dickinson’s dictum —it moved me as much as any so-called real, immortal art. And, to my amazement, the lines were free from the self-congratulation that Wallace Stevens warned against."

Likewise, this collection of Russell Edson prose poems took the top of my head off. And his work moves me as much as any writing I've ever read. Here are three of my favorites below. Hope you enjoy!

YOU

Out of nothing there comes a time called childhood, which is simply a path leading through an archway called adolescence. A small town there, past the arch called youth.

Soon, down the road, where one almost misses the life lived beyond the flower, is a small shack labeled, you.

And it is here the future lives in the several postures of arm on windowsill, cheek on this elbow on knees, face in the hands; sometimes the head thrown back, eyes staring into the ceiling . . . This into nothing down the long day’s arc . . .

THE WOUNDED BREAKFAST

A huge shoe mounts up from the horizon, squealing and grinding forward on small wheels, even as a man sitting to breakfast on his veranda is suddenly engulfed in a great shadow, almost the size of the night . . .

He looks up and sees a huge shoe ponderously mounting out of the earth.

Up in the unlaced ankle-part an old woman stands at a helm behind the great tongue curled forward; the thick laces dragging like ships' rope on the ground as the huge thing squeals and grinds forward; children everywhere, they look from the shoelace holes, they crowd about the old woman, even as she pilots this huge shoe over the earth . . .

Soon the huge shoe is descending the opposite horizon, a monstrous snail squealing and grinding into the earth . . .

The man turns to his breakfast again, but sees it's been wounded, the yolk of one of his eggs is bleeding . . .

THE RAT'S TIGHT SCHEDULE

A man stumbled on some rat droppings.

Hey, who put those there? That's dangerous, he said.

His wife said, those are pieces of a rat.

Wait, he's coming apart, he's all over the floor, said the husband.

He can't help it; you don't think he wants to drop pieces of himself all over the floor, do you? said the wife.

But I could have flipped and fallen through the floor, said the husband.

Well, he's been thinking of turning into a marsupial, so try to have a little patience. I'm sure if you were thinking of turning into a marsupial he'd be patient with you. But, on the other hand, don't embarrass him if he decides to remain placental, he's on a very tight schedule, said the wife.

A marsupial, a wonderful choice, cried the husband . . .

A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

“I am at the moment writing a lengthy indictment against our century. When my brain begins to reel from my literary labors, I make an occasional cheese dip.”

― John Kennedy Toole, A Confederacy of Dunces

A laugh-out-loud picaresque, a story chock-full of satire and unforgettable humorous detail as we follow the adventures of our larger-than-life rascal-hero, Ignatius J. Reilly, floundering and farting his way through New Orleans in the 1960s.

If you think of a novel-length R. Crumb cartoon you would not be far off. Some of the characters we meet: the manager of hot dog carts that sticks a long fork to the thick neck of Ignatius, the owner of a pants factory who constantly has to do verbal battle with his hypercritical, blackmailing wife, a sadistic police sergeant with a twisted, theatrical sense-of-humor and a thimble-brained stripper with a cockatoo. There is enough color and texture and satire to fill a dozen novels but somehow John Kennedy Toole manages to compress it all into his tightly-knit tale.

What really gives this story depth is the metaphysical dimension via Ignatius's worldview, which includes a careful reading of The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius and a keen awareness of Fortuna's wheel.

And we are right with Ignatius watching the wheel of Goddess Fortuna turn as we turn the pages. What an author; what a story; what a experience! Don't miss out. Get a copy of this book and get set for one of best literary rides of your life.

New Orleans author John Kennedy Toole (1937 - 1969)

“So we see that even when Fortuna spins us downward, the wheel sometimes halts for a moment and we find ourselves in a good, small cycle within the larger bad cycle. The universe, of course, is based upon the principle of the circle within the circle. At the moment, I am in an inner circle. Of course, smaller circles within this circle are also possible.”

― John Kennedy Toole, A Confederacy of Dunces

5.0

“I am at the moment writing a lengthy indictment against our century. When my brain begins to reel from my literary labors, I make an occasional cheese dip.”

― John Kennedy Toole, A Confederacy of Dunces

A laugh-out-loud picaresque, a story chock-full of satire and unforgettable humorous detail as we follow the adventures of our larger-than-life rascal-hero, Ignatius J. Reilly, floundering and farting his way through New Orleans in the 1960s.

If you think of a novel-length R. Crumb cartoon you would not be far off. Some of the characters we meet: the manager of hot dog carts that sticks a long fork to the thick neck of Ignatius, the owner of a pants factory who constantly has to do verbal battle with his hypercritical, blackmailing wife, a sadistic police sergeant with a twisted, theatrical sense-of-humor and a thimble-brained stripper with a cockatoo. There is enough color and texture and satire to fill a dozen novels but somehow John Kennedy Toole manages to compress it all into his tightly-knit tale.

What really gives this story depth is the metaphysical dimension via Ignatius's worldview, which includes a careful reading of The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius and a keen awareness of Fortuna's wheel.

And we are right with Ignatius watching the wheel of Goddess Fortuna turn as we turn the pages. What an author; what a story; what a experience! Don't miss out. Get a copy of this book and get set for one of best literary rides of your life.

New Orleans author John Kennedy Toole (1937 - 1969)

“So we see that even when Fortuna spins us downward, the wheel sometimes halts for a moment and we find ourselves in a good, small cycle within the larger bad cycle. The universe, of course, is based upon the principle of the circle within the circle. At the moment, I am in an inner circle. Of course, smaller circles within this circle are also possible.”

― John Kennedy Toole, A Confederacy of Dunces

The Aspern Papers by Henry James

In the section of his Moral Discourses entitled How a person can preserve their proper character in any situation the Stoic philosopher Epictetus says “You are the one who knows yourself – which is to say, you know how much you are worth in your own estimation, and therefore at what price you will sell yourself; because people sell themselves at different rates. Taking account of the value of externals, you see, comes at some cost to the value of one’s own character.”

I cite this quote since, in my reading of this Henry James novella, we are asked to ponder just this question as we follow the narrator’s quest for papers and letters penned by the late, great poet Jeffrey Aspern.

The first few chapters are like a work of fiction written in slow motion. But then through a series of revelations the story picks up serious momentum having the pace and timing of a detective novel, all the while suffused in the signature elegance of the author’s language, as in this scene where the narrator takes middle age Miss Tina for a ride on a warm summer evening, “We floated long and far, and though my friend gave no high-pitched voice to her glee I was sure of her full surrender. She was more than pleased, she was transported; the whole thing was an immense liberation. The gondola moved with slow strokes, to give her time to enjoy it, and she listened to the splash of the oars, which grew louder and more musically liquid as we passed into the narrow canals, as if it were a revelation of Venice.”

For me, the real philosophic and psychological juice of this fine tale comes in the closing chapter. I wouldn’t want to disclose any of the luscious details so as to spoil a reader’s fresh experience. Highly recommended.

5.0

In the section of his Moral Discourses entitled How a person can preserve their proper character in any situation the Stoic philosopher Epictetus says “You are the one who knows yourself – which is to say, you know how much you are worth in your own estimation, and therefore at what price you will sell yourself; because people sell themselves at different rates. Taking account of the value of externals, you see, comes at some cost to the value of one’s own character.”

I cite this quote since, in my reading of this Henry James novella, we are asked to ponder just this question as we follow the narrator’s quest for papers and letters penned by the late, great poet Jeffrey Aspern.

The first few chapters are like a work of fiction written in slow motion. But then through a series of revelations the story picks up serious momentum having the pace and timing of a detective novel, all the while suffused in the signature elegance of the author’s language, as in this scene where the narrator takes middle age Miss Tina for a ride on a warm summer evening, “We floated long and far, and though my friend gave no high-pitched voice to her glee I was sure of her full surrender. She was more than pleased, she was transported; the whole thing was an immense liberation. The gondola moved with slow strokes, to give her time to enjoy it, and she listened to the splash of the oars, which grew louder and more musically liquid as we passed into the narrow canals, as if it were a revelation of Venice.”

For me, the real philosophic and psychological juice of this fine tale comes in the closing chapter. I wouldn’t want to disclose any of the luscious details so as to spoil a reader’s fresh experience. Highly recommended.

The Crimes of Jordan Wise by Bill Pronzini

This Bill Pronzini novel is a compelling page-turner and will stick with you long after you have read the last page. Why? Because the story not only makes for good crime fiction but is a penetrating meditation on several key philosophical questions: what is the nature of love; what means should we take to realize our dreams; how valuable are such things as friendship, peace of mind and knowing oneself?

At the beginning of the novel, it appears to be a clear-cut case of Jordan’s love for sexually-charged, alluring Annalise, his like-minded female alter-ego, a twenty-six year old willing to do anything for a life of excitement and living on the edge. But the more Jordan tells his tale, the more the plot thickens, a thickness that’s as dark and as rich as Jordan’s favorite rum, Arundel Cane, the only run he ever drinks.

Jordan also loves sailing, especially as captain of his very own yawl, the feel of the wind in his face, the tropical sun overhead, the exhilaration of being on the wide, open sea.

And Jordan comes to loves Bone, a fiercely independently minded Caribbean man whose skin is "the color of milk chocolate," an expert seaman who acts as his mentor, the man who later becomes Jordan’s best and only friend.

Lastly, we come to understand Jordan has another love, perhaps his deepest love of all, a love that grounds him in the world and gives him a sense of identity, a very, very special identity – his perfect crimes.

Oh, Jordan, through your well-calculated plan of embezzlement, you set yourself free from the work-a-day white-collar world of your office, where you spent ten years crunching numbers as a trustworthy, accountant. You can now live on a Caribbean island with your lover Annalise and take up sailing by day and drinking your rum and having great sex by night. What a life! What a dream come true!

If only this life could go on and on for you. But there’s the rub. Life is forever changing, forever evolving or devolving – over time, the dream can vanish so quickly. And it did for you.

Ancient philosophers from Plato to Aristotle to Cicero, Seneca and Epicurus put great emphasis on friendship as an indispensable part of the good life. Jordan’s friendship with Bone has all the soulful qualities those ancient philosophers spoke about in such glowing terms. When Bone is not longer a friend, Jordan finds out the hard way just how much wisdom is contained in the words of those Greco-Roman philosophers.

Toward the end of the novel, when Jordan appears to have life on his own terms, we read, “the tight, structured little world I established for myself on St. Thomas was secure. I could continue to indulge my simple tastes for the rest of my life. I could be at peace. Only I wasn’t.”

Rather than delving into the specifics of Jordan’s story, let’s pause and note how many ancient philosophers, most notably Epicurus, held ataraxia (a combination of tranquility and joy) to be life’s highest value and ultimate goal.

Epicurus reasoned without ataraxis, without peace of mind, no matter whatever else a man or woman has in life, their life doesn’t amount to that much. Jordan lived his dream, at least for a number of years, but ultimately, it wasn’t enough.

No doubt about Jordan having a dark side -he philosophizes about his own dark nature and also human nature in general. But how deep is his understanding?

American author Bill Pronzini, born 1943

5.0

This Bill Pronzini novel is a compelling page-turner and will stick with you long after you have read the last page. Why? Because the story not only makes for good crime fiction but is a penetrating meditation on several key philosophical questions: what is the nature of love; what means should we take to realize our dreams; how valuable are such things as friendship, peace of mind and knowing oneself?

At the beginning of the novel, it appears to be a clear-cut case of Jordan’s love for sexually-charged, alluring Annalise, his like-minded female alter-ego, a twenty-six year old willing to do anything for a life of excitement and living on the edge. But the more Jordan tells his tale, the more the plot thickens, a thickness that’s as dark and as rich as Jordan’s favorite rum, Arundel Cane, the only run he ever drinks.

Jordan also loves sailing, especially as captain of his very own yawl, the feel of the wind in his face, the tropical sun overhead, the exhilaration of being on the wide, open sea.

And Jordan comes to loves Bone, a fiercely independently minded Caribbean man whose skin is "the color of milk chocolate," an expert seaman who acts as his mentor, the man who later becomes Jordan’s best and only friend.

Lastly, we come to understand Jordan has another love, perhaps his deepest love of all, a love that grounds him in the world and gives him a sense of identity, a very, very special identity – his perfect crimes.

Oh, Jordan, through your well-calculated plan of embezzlement, you set yourself free from the work-a-day white-collar world of your office, where you spent ten years crunching numbers as a trustworthy, accountant. You can now live on a Caribbean island with your lover Annalise and take up sailing by day and drinking your rum and having great sex by night. What a life! What a dream come true!

If only this life could go on and on for you. But there’s the rub. Life is forever changing, forever evolving or devolving – over time, the dream can vanish so quickly. And it did for you.

Ancient philosophers from Plato to Aristotle to Cicero, Seneca and Epicurus put great emphasis on friendship as an indispensable part of the good life. Jordan’s friendship with Bone has all the soulful qualities those ancient philosophers spoke about in such glowing terms. When Bone is not longer a friend, Jordan finds out the hard way just how much wisdom is contained in the words of those Greco-Roman philosophers.

Toward the end of the novel, when Jordan appears to have life on his own terms, we read, “the tight, structured little world I established for myself on St. Thomas was secure. I could continue to indulge my simple tastes for the rest of my life. I could be at peace. Only I wasn’t.”

Rather than delving into the specifics of Jordan’s story, let’s pause and note how many ancient philosophers, most notably Epicurus, held ataraxia (a combination of tranquility and joy) to be life’s highest value and ultimate goal.

Epicurus reasoned without ataraxis, without peace of mind, no matter whatever else a man or woman has in life, their life doesn’t amount to that much. Jordan lived his dream, at least for a number of years, but ultimately, it wasn’t enough.

No doubt about Jordan having a dark side -he philosophizes about his own dark nature and also human nature in general. But how deep is his understanding?

American author Bill Pronzini, born 1943

Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy by William Barrett

I first read William Barrett's Irrational Man back in college and was inspired to spend the next several years reading Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Dostoyevsky, Kafka,, Berdyaev and Shestov. Quite a rewarding experience.

Having also participated in the arts and music and the study of aesthetics for many years, I revisited Barrett's book with an eye to what he has to say about existentialism's connection to modern art. Again, a most rewarding experience.

So, with this in mind, and also recognizing many others have posted reviews here, I will focus on The Testimony of Modern Art, offering three Barrett quotes coupled with my comments.

"The ordinary man is uncomfortable, angry, or derisive before the dislocation of forms in modern art, before its bold distortions, or arbitrary manipulations of objects." Barrett is pointing out the heart of the issue with modern art: it doesn't matter if the art is created by Picasso, Mondrian, Pollack, Dali or Rothko - non-realistic, abstract art is anti-middle class mindset, anti-Walt Disney, and counter to a routine, regimented, unexamined, on-the-surface way of living.

"Modern art thus begins, and sometimes ends, as a confession of spiritual poverty. That is its greatness and its triumph, but also the needle it jabs into the Philistine's sore spot, for the last thing he wants to be reminded of is his spiritual poverty." Again, if people in modern mass society today spend their lives in TV stupor, listening to muzak, preoccupied with the size of their houses and their cars and fretting over their pensions, this is spiritual poverty plain and simple. Barrett sees modern art as needle number one and existentialism as needle number two sticking and jabbing and pricking and poking people to wake up to the depths of their own human experience. Recall how Kierkegaard said he wanted to be the Socratic gadfly of Copenhagen.

"This century in art, André Malraux has said, will go down in history not as the period of abstract art but as the period in which all the art of the past, and from every quarter of the glove, became available to the painter and sculptor, and through them became part of our modern taste." This infusion of the world's non-Western traditions continues today. For example, if an American artist tomorrow combines realistic portraiture with Japanese brush strokes, any gallery-goer wouldn't think twice. Our modern day culture is truly a world-culture. Would you be at all surprised if your new next door neighbors were from India, China or Brazil; or, if another neighbor explores African dance or Kung Fu or Tibetan Buddhist meditation? The point Barrett is highlighting here is that the old, conventional, self-contained, exclusively Western categories that served Western societies for centuries are blown open by global future-shock. Thus, more fertile ground for modern artists, philosophers and writers.

One last comments, this one from the section The Rational Ordering of Society, where Barrett says, "In a society that requires of man only that he perform competently his own particular social function, man becomes identified with this function, and the rest of his being is allowed to subsist as best it can - usually to be dropped below the surface of consciousness and forgotten." If anything, with the advent of cell-phones, blackberries, I-pads and the internet, people are spending more waking hours fulfilling their role and function within society today then back in 1958 when Barrett wrote these words.

No doubt about it - reflecting and living one's life from one's spiritual and artistic depth is a great challenge in our brave new computerized world. Challenging but not impossible. Reading and reflecting on the existential philosophers is a way to reclaim our full humanness. I offer the following recommendations:

For anybody wanting to pursue a study of Existentialism, I would recommend reading the following literary works. All are short and each one can be read in a day:

Notes from Underground - Dostoyevsky

Metamorphosis - Kafka

The Death of Ivan Ilyich - Tolstoy

The Wall - Sartre

The Stranger - Camus

For those wishing to study Existentialism more as a philosophy, here are my recommendations (note: none are by Heidegger or Sartre, since the philosophic writing of these two authors tends to be dense and turgid):

The Meaning of the Creative Act - Berdyaev

Slavery and Freedom - Berdyaev

Attack Upon "Christendom - Kierkegaard

The Dawn of Day - Nietzsche

I and Thou - Buber

William Barrett, long time philosophy professor at NYC and interpreter of existentialism, 1913-1992

5.0

I first read William Barrett's Irrational Man back in college and was inspired to spend the next several years reading Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Dostoyevsky, Kafka,, Berdyaev and Shestov. Quite a rewarding experience.

Having also participated in the arts and music and the study of aesthetics for many years, I revisited Barrett's book with an eye to what he has to say about existentialism's connection to modern art. Again, a most rewarding experience.

So, with this in mind, and also recognizing many others have posted reviews here, I will focus on The Testimony of Modern Art, offering three Barrett quotes coupled with my comments.

"The ordinary man is uncomfortable, angry, or derisive before the dislocation of forms in modern art, before its bold distortions, or arbitrary manipulations of objects." Barrett is pointing out the heart of the issue with modern art: it doesn't matter if the art is created by Picasso, Mondrian, Pollack, Dali or Rothko - non-realistic, abstract art is anti-middle class mindset, anti-Walt Disney, and counter to a routine, regimented, unexamined, on-the-surface way of living.

"Modern art thus begins, and sometimes ends, as a confession of spiritual poverty. That is its greatness and its triumph, but also the needle it jabs into the Philistine's sore spot, for the last thing he wants to be reminded of is his spiritual poverty." Again, if people in modern mass society today spend their lives in TV stupor, listening to muzak, preoccupied with the size of their houses and their cars and fretting over their pensions, this is spiritual poverty plain and simple. Barrett sees modern art as needle number one and existentialism as needle number two sticking and jabbing and pricking and poking people to wake up to the depths of their own human experience. Recall how Kierkegaard said he wanted to be the Socratic gadfly of Copenhagen.

"This century in art, André Malraux has said, will go down in history not as the period of abstract art but as the period in which all the art of the past, and from every quarter of the glove, became available to the painter and sculptor, and through them became part of our modern taste." This infusion of the world's non-Western traditions continues today. For example, if an American artist tomorrow combines realistic portraiture with Japanese brush strokes, any gallery-goer wouldn't think twice. Our modern day culture is truly a world-culture. Would you be at all surprised if your new next door neighbors were from India, China or Brazil; or, if another neighbor explores African dance or Kung Fu or Tibetan Buddhist meditation? The point Barrett is highlighting here is that the old, conventional, self-contained, exclusively Western categories that served Western societies for centuries are blown open by global future-shock. Thus, more fertile ground for modern artists, philosophers and writers.

One last comments, this one from the section The Rational Ordering of Society, where Barrett says, "In a society that requires of man only that he perform competently his own particular social function, man becomes identified with this function, and the rest of his being is allowed to subsist as best it can - usually to be dropped below the surface of consciousness and forgotten." If anything, with the advent of cell-phones, blackberries, I-pads and the internet, people are spending more waking hours fulfilling their role and function within society today then back in 1958 when Barrett wrote these words.

No doubt about it - reflecting and living one's life from one's spiritual and artistic depth is a great challenge in our brave new computerized world. Challenging but not impossible. Reading and reflecting on the existential philosophers is a way to reclaim our full humanness. I offer the following recommendations:

For anybody wanting to pursue a study of Existentialism, I would recommend reading the following literary works. All are short and each one can be read in a day:

Notes from Underground - Dostoyevsky

Metamorphosis - Kafka

The Death of Ivan Ilyich - Tolstoy

The Wall - Sartre

The Stranger - Camus

For those wishing to study Existentialism more as a philosophy, here are my recommendations (note: none are by Heidegger or Sartre, since the philosophic writing of these two authors tends to be dense and turgid):

The Meaning of the Creative Act - Berdyaev

Slavery and Freedom - Berdyaev

Attack Upon "Christendom - Kierkegaard

The Dawn of Day - Nietzsche

I and Thou - Buber

William Barrett, long time philosophy professor at NYC and interpreter of existentialism, 1913-1992

Tres Cuentos by Virgilio Piñera

This collection of three tales from the great Virgilio Piñera of Cuba contains Meat, Insomnia and Swimming. The English translation of these delectable short stories may be found in Cold Tales, translated by Mark Schafer and published by Eridanos Press.

Many Cuban authors are known for their irreverence to authority and experimental flair. Virgilio Piñera is most certainly among the leaders in this illustrious tradition.

If you read only one piece to sample a taste of exactly how irreverent, the following short tale, Meat, is the one I would highly recommend. Please keep in mind this snapping work of fiction was published in the teeth of Fidel Castro’s communist government. I’ve read Meat again and again, savoring each mouthwatering sentence. Enjoy!

MEAT

It happened simply, without pretense. For reasons that need not be explained, the town was suffering from a meat shortage. Everyone was alarmed, and rather bitter comments were heard; revenge was even spoken of. But, as always, the protests did not develop beyond threats, and soon the afflicted townspeople were devouring the most diverse vegetables.

Only Mr. Ansaldo didn't follow the order of the day. With great tranquility, he began to sharpen an enormous kitchen knife and then, dropping his pants to his knees, he cut a beautiful fillet from his left buttock. Having cleaned and dressed the fillet with salt and vinegar, he passed it through the broiler and finally fried it in the big pan he used on Sundays for making tortillas. He sat at the table and began to savor his beautiful fillet. Just then, there was a knock at the door: it was Ansaldo's neighbor coming to vent his frustrations. . . . Ansaldo, with an elegant gesture, showed his neighbor the beautiful fillet. When his neighbor asked about it, Ansaldo simply displayed his left buttock. The facts were laid bare. The neighbor, overwhelmed and moved, left without saying a word to return shortly with the mayor of the town. The latter expressed to Ansaldo his intense desire that his beloved townspeople be nourished - as was Ansaldo - by drawing on their private reserves, that is to say, each from their own meat. The issue was soon resolved, and after outbursts from the well educated, Ansaldo went to the main square of the town to offer - as he characteristically phrased it - "a practical demonstration for the masses."

Once there, he explained that each person could cut two fillets, from their left buttock, just like the flesh-colored plaster model he had hanging from a shinning meathook. He showed how to cut two fillets not one, for if he had cut one beautiful fillet from his own left buttock, it was only right that no one should consume one fillet fewer. Once these points were cleared up, each person began to slice two fillets from his left buttock. It was a glorious spectacle, but it is requested that descriptions not be given out. Calculations were made concerning how long the town would enjoy the benefits of this meat. One distinguished physician predicted that a person weighing one hundred pounds (discounting viscera and the rest of the inedible organs) could eat meat for one hundred and forty days at the rate of half a pound a day. This calculation was, of course, deceptive. And what mattered was that each person could eat his beautiful fillet. Soon woman were heard speaking of the advantages of Mr. Ansaldo's idea. For example, those who had devoured their breasts didn't need to cover their torsos with cloth, and their dresses reached just above the navel. Some women - though not all of them - no longer spoke at all, for they had gobbled up their tongues (which, by the way, is the delicacy of monarchs). In the streets, the most amusing scenes occurred: two women who had not seen each other for a long time were unable to kiss each other: they had both used their lips to cook up some very successful fritters. The prison warden could not sign a convict's death setence because he had eaten the fleshy tips of his fingers, which, according to the best "gourmets" (of which the warden was one), gave rise to the well-worn phrase "finger-licking good."

There was some minor resistance. the ladies garment workers union registered their most formal protest with the appropriate authority, who responded by saying that it wasn't possible to create a slogan that might encourage women to patronize their tailors again. By the resistance was never significant, and did not in any way interrupt the townspeople's consumption of their own meat.

One of the most colorful events of that pleasant episode was the dissection of the town ballet dancer's last morsel of flesh. Out of respect for his art, he had left his beautiful toes for last. His neighbors observed that he had been extremely restless for days. There now remained only the fleshy tip of one big tow. At that point he invited his friends to attend the operation. In the middle of a bloody silence, he cut off the last portion, and, without even warming it up, dropped it into the hole that had once been his beautiful mouth. Every one present suddenly became very serious.

But life went on, and that was the important thing. And if, by chance . . . ? Was it because of this that the dancer's shoes could now be found in one of the rooms of the Museum of Illustrious Memorabilia? It's only certain that one of the most obese men in town (weighing over four hundred pounds) used up his whole reserve of disposable meat in the brief space of fifteen days (he was extremely fond of snacks and sweetmeats, and besides, his metabolism required large quantities). After a while, no one could ever find him. Evidently, he was hiding . . . But he was not the only one to hide; in fact, many others began to adopt identical behavior. And so, one morning Mrs. Orfila got no answer when she asked her son (who was in the process of devouring his left earlobe) where he had put something. Neither pleas nor threats did any good. The expert in missing persons was called in, but he couldn't produce anything more than a small pile of excrement on the spot where Mrs. Orfila swore her beloved son had just been sitting at the moment she was questioning him. But these little disturbances did not undermine the happiness of the inhabitants in the least. For how could a town that was assured of its subsistence complain? Hadn't the crisis of public order caused by the meat shortage been definitely resolved? That the population was increasingly dropping out of sight was but a postscript to the fundamental issue and did not affect the people's determination to obtain their vital sustenance. Was that postscript the price that the flesh exacted from each? But it would be petty to ask any more such inopportune questions, now that this thoughtful community was perfectly well fed.

Virgilio Piñera, Cuban poet and author of extraordinary fiction, 1912- 1979

5.0

This collection of three tales from the great Virgilio Piñera of Cuba contains Meat, Insomnia and Swimming. The English translation of these delectable short stories may be found in Cold Tales, translated by Mark Schafer and published by Eridanos Press.

Many Cuban authors are known for their irreverence to authority and experimental flair. Virgilio Piñera is most certainly among the leaders in this illustrious tradition.

If you read only one piece to sample a taste of exactly how irreverent, the following short tale, Meat, is the one I would highly recommend. Please keep in mind this snapping work of fiction was published in the teeth of Fidel Castro’s communist government. I’ve read Meat again and again, savoring each mouthwatering sentence. Enjoy!

MEAT

It happened simply, without pretense. For reasons that need not be explained, the town was suffering from a meat shortage. Everyone was alarmed, and rather bitter comments were heard; revenge was even spoken of. But, as always, the protests did not develop beyond threats, and soon the afflicted townspeople were devouring the most diverse vegetables.

Only Mr. Ansaldo didn't follow the order of the day. With great tranquility, he began to sharpen an enormous kitchen knife and then, dropping his pants to his knees, he cut a beautiful fillet from his left buttock. Having cleaned and dressed the fillet with salt and vinegar, he passed it through the broiler and finally fried it in the big pan he used on Sundays for making tortillas. He sat at the table and began to savor his beautiful fillet. Just then, there was a knock at the door: it was Ansaldo's neighbor coming to vent his frustrations. . . . Ansaldo, with an elegant gesture, showed his neighbor the beautiful fillet. When his neighbor asked about it, Ansaldo simply displayed his left buttock. The facts were laid bare. The neighbor, overwhelmed and moved, left without saying a word to return shortly with the mayor of the town. The latter expressed to Ansaldo his intense desire that his beloved townspeople be nourished - as was Ansaldo - by drawing on their private reserves, that is to say, each from their own meat. The issue was soon resolved, and after outbursts from the well educated, Ansaldo went to the main square of the town to offer - as he characteristically phrased it - "a practical demonstration for the masses."

Once there, he explained that each person could cut two fillets, from their left buttock, just like the flesh-colored plaster model he had hanging from a shinning meathook. He showed how to cut two fillets not one, for if he had cut one beautiful fillet from his own left buttock, it was only right that no one should consume one fillet fewer. Once these points were cleared up, each person began to slice two fillets from his left buttock. It was a glorious spectacle, but it is requested that descriptions not be given out. Calculations were made concerning how long the town would enjoy the benefits of this meat. One distinguished physician predicted that a person weighing one hundred pounds (discounting viscera and the rest of the inedible organs) could eat meat for one hundred and forty days at the rate of half a pound a day. This calculation was, of course, deceptive. And what mattered was that each person could eat his beautiful fillet. Soon woman were heard speaking of the advantages of Mr. Ansaldo's idea. For example, those who had devoured their breasts didn't need to cover their torsos with cloth, and their dresses reached just above the navel. Some women - though not all of them - no longer spoke at all, for they had gobbled up their tongues (which, by the way, is the delicacy of monarchs). In the streets, the most amusing scenes occurred: two women who had not seen each other for a long time were unable to kiss each other: they had both used their lips to cook up some very successful fritters. The prison warden could not sign a convict's death setence because he had eaten the fleshy tips of his fingers, which, according to the best "gourmets" (of which the warden was one), gave rise to the well-worn phrase "finger-licking good."

There was some minor resistance. the ladies garment workers union registered their most formal protest with the appropriate authority, who responded by saying that it wasn't possible to create a slogan that might encourage women to patronize their tailors again. By the resistance was never significant, and did not in any way interrupt the townspeople's consumption of their own meat.

One of the most colorful events of that pleasant episode was the dissection of the town ballet dancer's last morsel of flesh. Out of respect for his art, he had left his beautiful toes for last. His neighbors observed that he had been extremely restless for days. There now remained only the fleshy tip of one big tow. At that point he invited his friends to attend the operation. In the middle of a bloody silence, he cut off the last portion, and, without even warming it up, dropped it into the hole that had once been his beautiful mouth. Every one present suddenly became very serious.

But life went on, and that was the important thing. And if, by chance . . . ? Was it because of this that the dancer's shoes could now be found in one of the rooms of the Museum of Illustrious Memorabilia? It's only certain that one of the most obese men in town (weighing over four hundred pounds) used up his whole reserve of disposable meat in the brief space of fifteen days (he was extremely fond of snacks and sweetmeats, and besides, his metabolism required large quantities). After a while, no one could ever find him. Evidently, he was hiding . . . But he was not the only one to hide; in fact, many others began to adopt identical behavior. And so, one morning Mrs. Orfila got no answer when she asked her son (who was in the process of devouring his left earlobe) where he had put something. Neither pleas nor threats did any good. The expert in missing persons was called in, but he couldn't produce anything more than a small pile of excrement on the spot where Mrs. Orfila swore her beloved son had just been sitting at the moment she was questioning him. But these little disturbances did not undermine the happiness of the inhabitants in the least. For how could a town that was assured of its subsistence complain? Hadn't the crisis of public order caused by the meat shortage been definitely resolved? That the population was increasingly dropping out of sight was but a postscript to the fundamental issue and did not affect the people's determination to obtain their vital sustenance. Was that postscript the price that the flesh exacted from each? But it would be petty to ask any more such inopportune questions, now that this thoughtful community was perfectly well fed.

Virgilio Piñera, Cuban poet and author of extraordinary fiction, 1912- 1979