Scan barcode

glenncolerussell's reviews

1456 reviews

Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House by Michael Wolff

When I wrote my surreal microfiction in years past, many the time I would remember a dream I had the previous night and stumble down to my computer to convert the dream into words, sometimes with very little editing.

After reading a number of reviews of this book here on Goodreads, I had a dream about the book last night that I turned into the following microfiction – no editing, this was the actual dream, beginning to end. Apologies to fans of our current president – please keep in mind the muse can work in strange ways. Anyway, here it is:

THE BABOON CONCERTO

The musicians in a symphony orchestra are all set to play their next piece of classical music to a full house. It’s a concerto for bassoon.

Out comes the bassoonist in his tuxedo. None other than our current president.

There’s murmuring among both the audience and the members of the orchestra for the bassoonist isn’t holding a bassoon, he’s carrying a baboon. The conductor cries: “What on earth are you doing!”

The bassoonist replies calmly: “A bassoon is a reed instrument. I stuck a reed in the baboon’s throat. When I squeeze its belly, it plays beautiful bassoon music.

The conductor raises his baton and the orchestra starts playing. The bassoonist doesn’t miss a note.

Following the last rousing phrases of the concerto, the orchestra stands to bask in the glow of a standing ovation. The bassoonist and his baboon likewise stand and take their bows, both grinning their silly grins.

After reading a number of reviews of this book here on Goodreads, I had a dream about the book last night that I turned into the following microfiction – no editing, this was the actual dream, beginning to end. Apologies to fans of our current president – please keep in mind the muse can work in strange ways. Anyway, here it is:

THE BABOON CONCERTO

The musicians in a symphony orchestra are all set to play their next piece of classical music to a full house. It’s a concerto for bassoon.

Out comes the bassoonist in his tuxedo. None other than our current president.

There’s murmuring among both the audience and the members of the orchestra for the bassoonist isn’t holding a bassoon, he’s carrying a baboon. The conductor cries: “What on earth are you doing!”

The bassoonist replies calmly: “A bassoon is a reed instrument. I stuck a reed in the baboon’s throat. When I squeeze its belly, it plays beautiful bassoon music.

The conductor raises his baton and the orchestra starts playing. The bassoonist doesn’t miss a note.

Following the last rousing phrases of the concerto, the orchestra stands to bask in the glow of a standing ovation. The bassoonist and his baboon likewise stand and take their bows, both grinning their silly grins.

The Bull by Saki

“From the essential nature of the philistine it follows, secondly, in regard to others, that, as he possesses no intellectual, but only physical need, he will seek the society of those who can satisfy the latter, but not the former. The last thing he will expect from his friends is the possession of any sort of intellectual capacity; nay, if he chances to meet with it, it will rouse his antipathy and even hatred; simply because in addition to an unpleasant sense of inferiority, he experiences, in his heart, a dull kind of envy, which has to be carefully concealed even from himself.”

Too bad Laurence the painter of animals didn’t heed the above wise words of Arthur Schopenhauer and keep his mouth shut at the appropriate time. Would have saved himself a helping of bumps and bruises and broken bones.

With this short tale of two half-brothers English author Saki captures to perfection the tension between practical men and women of the world on one side and those rarefied artists, intellectuals and aesthetes on the other.

THE BULL

Tom Yorkfield had always regarded his half-brother, Laurence, with a lazy instinct of dislike, toned down, as years went on, to a tolerant feeling of indifference. There was nothing very tangible to dislike him for; he was just a blood-relation, with whom Tom had no single taste or interest in common, and with whom, at the same time, he had had no occasion for quarrel. Laurence had left the farm early in life, and had lived for a few years on a small sum of money left him by his mother; he had taken up painting as a profession, and was reported to be doing fairly well at it, well enough, at any rate, to keep body and soul together. He specialized in painting animals, and he was successful in finding a certain number of people to buy his pictures. Tom felt a comforting sense of assured superiority in contrasting his position with that of his half-brother; Laurence was an artist-chap, just that and nothing more, though you might make it sound more important by calling him an animal painter; Tom was a farmer, not in a very big way, it was true, but the Helsery farm had been in the family for some generations, and it had a good reputation for the stock raised on it. Tom had done his best, with the little capital at his command, to maintain and improve the standard of his small herd of cattle, and in Clover Fairy he had bred a bull which was something rather better than any that his immediate neighbors could show. It would not have made a sensation in the judging-ring at an important cattle show, but it was as vigorous, shapely, and healthy a young animal as any small practical farmer could wish to possess. At the King's Head on market days Clover Fairy was very highly spoken of, and Yorkfield used to declare that he would not part with him for a hundred pounds; a hundred pounds is a lot of money in the small farming line, and probably anything over eighty would have tempted him.

It was with some especial pleasure that Tom took advantage of one of Laurence's rare visits to the farm to lead him down to the enclosure where Clover Fairy kept solitary state -- the grass widower of a grazing harem. Tom felt some of his old dislike for his halfbrother reviving; the artist was becoming more languid in his manner, more unsuitably turned-out in attire, and he seemed inclined to impart a slightly patronizing tone to his conversation. He took no heed of a flourishing potato crop, but waxed enthusiastic over a clump of yellow-flowering weed that stood in a corner by a gateway, which was rather galling to the owner of a really very well weeded farm; again, when he might have been duly complimentary about a group of fat, black-faced lambs, that simply cried aloud for admiration, he became eloquent over the foliage tints of an oak copse on the hill opposite. But now he was being taken to inspect the crowning pride and glory of Helsery; however grudging he might be in his praises, however backward and niggardly with his congratulations, he would have to see and acknowledge the many excellences of that redoubtable animal. Some weeks ago, while on a business journey to Taunton, Tom had been invited by his halfbrother to visit a studio in that town, where Laurence was exhibiting one of his pictures, a large canvas representing a bull standing knee-deep in some marshy ground; it had been good of its kind, no doubt, and Laurence had seemed inordinately pleased with it; "the best thing I've done yet," he had said over and over again, and Tom had generously agreed that it was fairly life-like. Now, the man of pigments was going to be shown a real picture, a living model of strength and comeliness, a thing to feast the eyes on, a picture that exhibited new pose and action with every shifting minute, instead of standing glued into one unvarying attitude between the four walls of a frame. Tom unfastened a stout wooden door and led the way into a straw-bedded yard.

"Is he quiet?" asked the artist, as a young bull with a curly red coat came inquiringly towards them.

"He's playful at times," said Tom, leaving his half-brother to wonder whether the bull's ideas of play were of the catch-as-catch can order. Laurence made one or two perfunctory comments on the animal's appearance and asked a question or so as to his age and such-like details; then he coolly turned the talk into another channel.

"Do you remember the picture I showed you at Taunton?" he asked.

"Yes," grunted Tom; "a white-faced bull standing in some slush. Don't admire those Herefords much myself; bulky-looking brutes, don't seem to have much life in them. Daresay they're easier to paint that way; now, this young beggar is on the move all the time, aren't you, Fairy?"

"I've sold that picture," said Laurence, with considerable complacency in his voice.

"Have you?" said Tom; "glad to hear it, I'm sure. Hope you're pleased with what you've got for it."

"I got three hundred pounds for it," said Laurence.

Tom turned towards him with a slowly rising flush of anger in his face. Three hundred pounds! Under the most favourable market conditions that he could imagine his prized Clover Fairy would hardly fetch a hundred, yet here was a piece of varnished canvas, painted by his half-brother, selling for three times that sum. It was a cruel insult that went home with all the more force because it emphasized the triumph of the patronizing, self-satisfied Laurence. The young farmer had meant to put his relative just a little out of conceit with himself by displaying the jewel of his possessions, and now the tables were turned, and his valued beast was made to look cheap and insignificant beside the price paid for a mere picture. It was so monstrously unjust; the painting would never be anything more than a dexterous piece of counterfeit life, while Clover Fairy was the real thing, a monarch in his little world, a personality in the countryside. After he was dead, even, he would still be something of a personality; his descendants would graze in those valley meadows and hillside pastures, they would fill stall and byre and milking-shed, their good red coats would speckle the landscape and crowd the market-place; men would note a promising heifer or a well-proportioned steer, and say: "Ah, that one comes of good old Clover Fairy's stock." All that time the picture would be hanging, lifeless and unchanging, beneath its dust and varnish, a chattel that ceased to mean anything if you chose to turn it with its back to the wall. These thoughts chased themselves angrily through Tom Yorkfield's mind, but he could not put them into words. When he gave tongue to his feelings he put matters bluntly and harshly.

"Some soft-witted fools may like to throw away three hundred pounds on a bit of paintwork; can't say as I envy them their taste. I'd rather have the real thing than a picture of it."

He nodded towards the young bull, that was alternately staring at them with nose held high and lowering its horns with a half-playful, half-impatient shake of the head.

Laurence laughed a laugh of irritating, indulgent amusement.

"I don't think the purchaser of my bit of paintwork, as you call it, need worry about having thrown his money away. As I get to be better known and recognized my pictures will go up in value. That particular one will probably fetch four hundred in a sale-room five or six years hence; pictures aren't a bad investment if you know enough to pick out the work of the right men. Now you can't say your precious bull is going to get more valuable the longer you keep him; he'll have his little day, and then, if you go on keeping him, he'll come down at last to a few shillingsworth of hoofs and hide, just at a time, perhaps, when my bull is being bought for a big sum for some important picture gallery."

It was too much. The united force of truth and slander and insult put over heavy a strain on Tom Yorkfield's powers of restraint. In his right hand he held a useful oak cudgel, with his left he made a grab at the loose collar of Laurence's canary-colored silk shirt. Laurence was not a fighting man; the fear of physical violence threw him off his balance as completely as overmastering indignation had thrown Tom off his, and thus it came to pass that Clover Fairy was regaled with the unprecedented sight of a human being scudding and squawking across the enclosure, like the hen that would persist in trying to establish a nesting-place in the manger. In another crowded happy moment the bull was trying to jerk Laurence over his left shoulder, to prod him in the ribs while still in the air, and to kneel on him when he reached the ground. It was only the vigorous intervention of Tom that induced him to relinquish the last item of his programme.

Tom devotedly and ungrudgingly nursed his half brother to a complete recovery from his injuries, which consisted of nothing more serious than a dislocated shoulder, a broken rib or two, and a little nervous prostration. After all, there was no further occasion for rancor in the young farmer's mind; Laurence's bull might sell for three hundred, or for six hundred, and be admired by thousands in some big picture gallery, but it would never toss a man over one shoulder and catch him a jab in the ribs before he had fallen on the other side. That was Clover Fairy's noteworthy achievement, which could never be taken away from him.

Laurence continues to be popular as an animal artist, but his subjects are always kittens or fawns or lambkins -- never bulls.

5.0

“From the essential nature of the philistine it follows, secondly, in regard to others, that, as he possesses no intellectual, but only physical need, he will seek the society of those who can satisfy the latter, but not the former. The last thing he will expect from his friends is the possession of any sort of intellectual capacity; nay, if he chances to meet with it, it will rouse his antipathy and even hatred; simply because in addition to an unpleasant sense of inferiority, he experiences, in his heart, a dull kind of envy, which has to be carefully concealed even from himself.”

Too bad Laurence the painter of animals didn’t heed the above wise words of Arthur Schopenhauer and keep his mouth shut at the appropriate time. Would have saved himself a helping of bumps and bruises and broken bones.

With this short tale of two half-brothers English author Saki captures to perfection the tension between practical men and women of the world on one side and those rarefied artists, intellectuals and aesthetes on the other.

THE BULL

Tom Yorkfield had always regarded his half-brother, Laurence, with a lazy instinct of dislike, toned down, as years went on, to a tolerant feeling of indifference. There was nothing very tangible to dislike him for; he was just a blood-relation, with whom Tom had no single taste or interest in common, and with whom, at the same time, he had had no occasion for quarrel. Laurence had left the farm early in life, and had lived for a few years on a small sum of money left him by his mother; he had taken up painting as a profession, and was reported to be doing fairly well at it, well enough, at any rate, to keep body and soul together. He specialized in painting animals, and he was successful in finding a certain number of people to buy his pictures. Tom felt a comforting sense of assured superiority in contrasting his position with that of his half-brother; Laurence was an artist-chap, just that and nothing more, though you might make it sound more important by calling him an animal painter; Tom was a farmer, not in a very big way, it was true, but the Helsery farm had been in the family for some generations, and it had a good reputation for the stock raised on it. Tom had done his best, with the little capital at his command, to maintain and improve the standard of his small herd of cattle, and in Clover Fairy he had bred a bull which was something rather better than any that his immediate neighbors could show. It would not have made a sensation in the judging-ring at an important cattle show, but it was as vigorous, shapely, and healthy a young animal as any small practical farmer could wish to possess. At the King's Head on market days Clover Fairy was very highly spoken of, and Yorkfield used to declare that he would not part with him for a hundred pounds; a hundred pounds is a lot of money in the small farming line, and probably anything over eighty would have tempted him.

It was with some especial pleasure that Tom took advantage of one of Laurence's rare visits to the farm to lead him down to the enclosure where Clover Fairy kept solitary state -- the grass widower of a grazing harem. Tom felt some of his old dislike for his halfbrother reviving; the artist was becoming more languid in his manner, more unsuitably turned-out in attire, and he seemed inclined to impart a slightly patronizing tone to his conversation. He took no heed of a flourishing potato crop, but waxed enthusiastic over a clump of yellow-flowering weed that stood in a corner by a gateway, which was rather galling to the owner of a really very well weeded farm; again, when he might have been duly complimentary about a group of fat, black-faced lambs, that simply cried aloud for admiration, he became eloquent over the foliage tints of an oak copse on the hill opposite. But now he was being taken to inspect the crowning pride and glory of Helsery; however grudging he might be in his praises, however backward and niggardly with his congratulations, he would have to see and acknowledge the many excellences of that redoubtable animal. Some weeks ago, while on a business journey to Taunton, Tom had been invited by his halfbrother to visit a studio in that town, where Laurence was exhibiting one of his pictures, a large canvas representing a bull standing knee-deep in some marshy ground; it had been good of its kind, no doubt, and Laurence had seemed inordinately pleased with it; "the best thing I've done yet," he had said over and over again, and Tom had generously agreed that it was fairly life-like. Now, the man of pigments was going to be shown a real picture, a living model of strength and comeliness, a thing to feast the eyes on, a picture that exhibited new pose and action with every shifting minute, instead of standing glued into one unvarying attitude between the four walls of a frame. Tom unfastened a stout wooden door and led the way into a straw-bedded yard.

"Is he quiet?" asked the artist, as a young bull with a curly red coat came inquiringly towards them.

"He's playful at times," said Tom, leaving his half-brother to wonder whether the bull's ideas of play were of the catch-as-catch can order. Laurence made one or two perfunctory comments on the animal's appearance and asked a question or so as to his age and such-like details; then he coolly turned the talk into another channel.

"Do you remember the picture I showed you at Taunton?" he asked.

"Yes," grunted Tom; "a white-faced bull standing in some slush. Don't admire those Herefords much myself; bulky-looking brutes, don't seem to have much life in them. Daresay they're easier to paint that way; now, this young beggar is on the move all the time, aren't you, Fairy?"

"I've sold that picture," said Laurence, with considerable complacency in his voice.

"Have you?" said Tom; "glad to hear it, I'm sure. Hope you're pleased with what you've got for it."

"I got three hundred pounds for it," said Laurence.

Tom turned towards him with a slowly rising flush of anger in his face. Three hundred pounds! Under the most favourable market conditions that he could imagine his prized Clover Fairy would hardly fetch a hundred, yet here was a piece of varnished canvas, painted by his half-brother, selling for three times that sum. It was a cruel insult that went home with all the more force because it emphasized the triumph of the patronizing, self-satisfied Laurence. The young farmer had meant to put his relative just a little out of conceit with himself by displaying the jewel of his possessions, and now the tables were turned, and his valued beast was made to look cheap and insignificant beside the price paid for a mere picture. It was so monstrously unjust; the painting would never be anything more than a dexterous piece of counterfeit life, while Clover Fairy was the real thing, a monarch in his little world, a personality in the countryside. After he was dead, even, he would still be something of a personality; his descendants would graze in those valley meadows and hillside pastures, they would fill stall and byre and milking-shed, their good red coats would speckle the landscape and crowd the market-place; men would note a promising heifer or a well-proportioned steer, and say: "Ah, that one comes of good old Clover Fairy's stock." All that time the picture would be hanging, lifeless and unchanging, beneath its dust and varnish, a chattel that ceased to mean anything if you chose to turn it with its back to the wall. These thoughts chased themselves angrily through Tom Yorkfield's mind, but he could not put them into words. When he gave tongue to his feelings he put matters bluntly and harshly.

"Some soft-witted fools may like to throw away three hundred pounds on a bit of paintwork; can't say as I envy them their taste. I'd rather have the real thing than a picture of it."

He nodded towards the young bull, that was alternately staring at them with nose held high and lowering its horns with a half-playful, half-impatient shake of the head.

Laurence laughed a laugh of irritating, indulgent amusement.

"I don't think the purchaser of my bit of paintwork, as you call it, need worry about having thrown his money away. As I get to be better known and recognized my pictures will go up in value. That particular one will probably fetch four hundred in a sale-room five or six years hence; pictures aren't a bad investment if you know enough to pick out the work of the right men. Now you can't say your precious bull is going to get more valuable the longer you keep him; he'll have his little day, and then, if you go on keeping him, he'll come down at last to a few shillingsworth of hoofs and hide, just at a time, perhaps, when my bull is being bought for a big sum for some important picture gallery."

It was too much. The united force of truth and slander and insult put over heavy a strain on Tom Yorkfield's powers of restraint. In his right hand he held a useful oak cudgel, with his left he made a grab at the loose collar of Laurence's canary-colored silk shirt. Laurence was not a fighting man; the fear of physical violence threw him off his balance as completely as overmastering indignation had thrown Tom off his, and thus it came to pass that Clover Fairy was regaled with the unprecedented sight of a human being scudding and squawking across the enclosure, like the hen that would persist in trying to establish a nesting-place in the manger. In another crowded happy moment the bull was trying to jerk Laurence over his left shoulder, to prod him in the ribs while still in the air, and to kneel on him when he reached the ground. It was only the vigorous intervention of Tom that induced him to relinquish the last item of his programme.

Tom devotedly and ungrudgingly nursed his half brother to a complete recovery from his injuries, which consisted of nothing more serious than a dislocated shoulder, a broken rib or two, and a little nervous prostration. After all, there was no further occasion for rancor in the young farmer's mind; Laurence's bull might sell for three hundred, or for six hundred, and be admired by thousands in some big picture gallery, but it would never toss a man over one shoulder and catch him a jab in the ribs before he had fallen on the other side. That was Clover Fairy's noteworthy achievement, which could never be taken away from him.

Laurence continues to be popular as an animal artist, but his subjects are always kittens or fawns or lambkins -- never bulls.

The Reason Why the Closet-Man Is Never Sad by Russell Edson

Here are four of my favorite Russell Edson pieces from this collection that I've read over and over and over again. Somewhat in the same spirit, at the very bottom is my own micro-fiction I had published some years back.

THE AUTOPSY

In a back room a man is performing an autopsy on an old raincoat.

His wife appears in the doorway with a candle and asks, how does it go?

Not now, not now, I'm just getting to the lining, he murmurs with impatience.

I just wanted to know if you found any blood clots?

Blood clots?

For my necklace . . .

THE CLOSET

Here I am with my mother, hanging under the molt of years, in a garden of umbrellas and rubber boots, together always in the vague perfume of her coat.

See how the fedoras along the shelf are the several skulls of my father, in this catacomb of my family.

THE LONELY TRAVELER

He's a lonely traveler, and finds companion in the road; a chance meeting, seeing as how they were both going the same way.

. . . only, the road has already arrived at its end; like a long snake, its eyes closed in the distance asleep . . .

THROUGH THE DARKNESS OF SLEEP

In sleep: softly, softly, angel soldiers mob us with their brutal wings; stepping from the clouds they break through the attic like divers into a sunken ship.

A handful of shingles they hold, leafing through them like the pages of our lives; the book of the roof: here is the legend of the moss and the weather, and here the story of the overturned ship, sunken, barnacled by the markings of birds . . .

. . . We are to be led away, one by one, through the darkness of sleep, through the mica glitter of stars, down the stairways of our beds, into the roots of trees . . . slowly surrendering, tossing and turning through centuries of darkness . . .

TAKING A SHOWER

A man is about to step into the shower when he discovers a chimpanzee in the tub.

"Well, let's give you a little water," the man says as he bends over and with a snap of the wrist turns on the hot.

The chimpanzee starts shrieking and tries desperately to get out. By that time, though, the man has pulled the shower curtain closed and punches at the outline of the chimp through the cloth.

The door creeks open. Alarmed, the man twists around and sees another chimpanzee lope in; outnumbered he bolts.

Now his eyes really bulge, his naked flesh trembles. The hallway is full of chimpanzees. And when the chimps gander at his horrified face, they all start jumping up and down, baring their teeth, creating a din with their high-pitched screeching. Surging forward, flailing his arms like an over-wound windup toy, the man takes a running leap toward the stairs leading down to the parlor where his wife is hosting afternoon tea.

The chimps clutch at him with their hairy arms, and when he tumbles down the stairs, no less than seven chimps tumble with him. The mass of hair, teeth, penises, tails and white sweaty flanks crash at the foot of the stairs.

The ladies glance over from their tea for a moment and continue their conversation.

Untangling themselves, the embarrassed chimps race out the back door and are followed quickly by their fellows who stampede down the stairs, trample the man's legs, and head on the way.

The man ceremoniously picks himself up, bows to the ladies, executes a left face, and marches back up the stairs and into the bathroom. Clutching the soap with a burly hand, he proceeds to scrub himself. Just when he's about to reach for the shampoo, the first chimp vaults back into the tub. Hastily, the man snatches him up by the neck and tail, sprints to the head of the stairs, and flings the chimp airborne to the bottom.

"Your first flying lesson," he snickers, brushing off his palms one against another with a flourish.

He stomps back to the bathroom that by this time has really steamed up. There's a wet bar of soap on the floor - his foot hits it. He takes a nasty fall. Unable to get up, he writhes in pain on the white hexagonal tiles.

Meanwhile, all the chimps come rumbling back up the stairs, trample over his belly, and pile into the tub.

"The soap, sir, where is the soap?" the chimp, now wearing aviator goggles, beseeches, and then spotting the shining bar in the corner, steps out to retrieve it. The man splutters pleas for help, but his voice is drowned out by all the whooping.

5.0

Here are four of my favorite Russell Edson pieces from this collection that I've read over and over and over again. Somewhat in the same spirit, at the very bottom is my own micro-fiction I had published some years back.

THE AUTOPSY

In a back room a man is performing an autopsy on an old raincoat.

His wife appears in the doorway with a candle and asks, how does it go?

Not now, not now, I'm just getting to the lining, he murmurs with impatience.

I just wanted to know if you found any blood clots?

Blood clots?

For my necklace . . .

THE CLOSET

Here I am with my mother, hanging under the molt of years, in a garden of umbrellas and rubber boots, together always in the vague perfume of her coat.

See how the fedoras along the shelf are the several skulls of my father, in this catacomb of my family.

THE LONELY TRAVELER

He's a lonely traveler, and finds companion in the road; a chance meeting, seeing as how they were both going the same way.

. . . only, the road has already arrived at its end; like a long snake, its eyes closed in the distance asleep . . .

THROUGH THE DARKNESS OF SLEEP

In sleep: softly, softly, angel soldiers mob us with their brutal wings; stepping from the clouds they break through the attic like divers into a sunken ship.

A handful of shingles they hold, leafing through them like the pages of our lives; the book of the roof: here is the legend of the moss and the weather, and here the story of the overturned ship, sunken, barnacled by the markings of birds . . .

. . . We are to be led away, one by one, through the darkness of sleep, through the mica glitter of stars, down the stairways of our beds, into the roots of trees . . . slowly surrendering, tossing and turning through centuries of darkness . . .

TAKING A SHOWER

A man is about to step into the shower when he discovers a chimpanzee in the tub.

"Well, let's give you a little water," the man says as he bends over and with a snap of the wrist turns on the hot.

The chimpanzee starts shrieking and tries desperately to get out. By that time, though, the man has pulled the shower curtain closed and punches at the outline of the chimp through the cloth.

The door creeks open. Alarmed, the man twists around and sees another chimpanzee lope in; outnumbered he bolts.

Now his eyes really bulge, his naked flesh trembles. The hallway is full of chimpanzees. And when the chimps gander at his horrified face, they all start jumping up and down, baring their teeth, creating a din with their high-pitched screeching. Surging forward, flailing his arms like an over-wound windup toy, the man takes a running leap toward the stairs leading down to the parlor where his wife is hosting afternoon tea.

The chimps clutch at him with their hairy arms, and when he tumbles down the stairs, no less than seven chimps tumble with him. The mass of hair, teeth, penises, tails and white sweaty flanks crash at the foot of the stairs.

The ladies glance over from their tea for a moment and continue their conversation.

Untangling themselves, the embarrassed chimps race out the back door and are followed quickly by their fellows who stampede down the stairs, trample the man's legs, and head on the way.

The man ceremoniously picks himself up, bows to the ladies, executes a left face, and marches back up the stairs and into the bathroom. Clutching the soap with a burly hand, he proceeds to scrub himself. Just when he's about to reach for the shampoo, the first chimp vaults back into the tub. Hastily, the man snatches him up by the neck and tail, sprints to the head of the stairs, and flings the chimp airborne to the bottom.

"Your first flying lesson," he snickers, brushing off his palms one against another with a flourish.

He stomps back to the bathroom that by this time has really steamed up. There's a wet bar of soap on the floor - his foot hits it. He takes a nasty fall. Unable to get up, he writhes in pain on the white hexagonal tiles.

Meanwhile, all the chimps come rumbling back up the stairs, trample over his belly, and pile into the tub.

"The soap, sir, where is the soap?" the chimp, now wearing aviator goggles, beseeches, and then spotting the shining bar in the corner, steps out to retrieve it. The man splutters pleas for help, but his voice is drowned out by all the whooping.

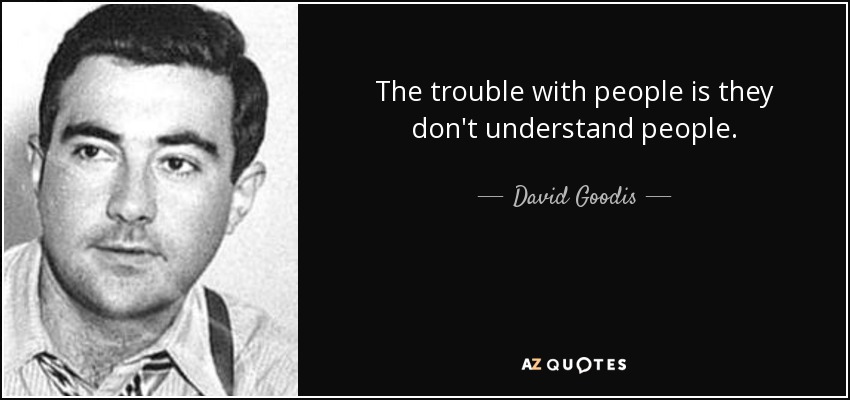

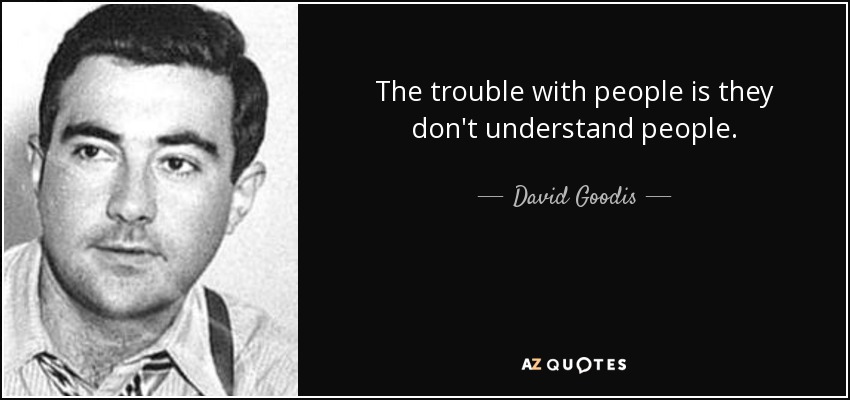

Shoot the Piano Player by David Goodis

This gritty, hard-boiled novel by David Goodis opens with an action scene where a bloody-faced Turley Linn is running for his life through the alleys of a Philadelphia slum, fleeing from two professional hit-men. Turley ducks into a run-down neighborhood bar called Harriet's Hut and finds his brother Eddie (the novel's main character) who he hasn't seen in over six years. Eddie acknowledges his brother but remains cool and doesn't stop playing his sweet honky-tonk music on the joint's piano. Remaining cool, detached and emotionally uninvolved is the key note (no pun intended) of Eddie's threadbare, solitary life.

In the first few pages we also come to know there is another side to cool Eddie, that is, some years ago Edward Webster Lynn, a concert pianist trained at the Curtis Institute, toured Europe and performed at Carnegie Hall, captivating and mesmerizing audiences with musical talent bordering on genius.

Then why, we may ask, is one of the world's greatest pianists tickling the eighty-eight at a rundown bar? It isn't until midway through the novel that we are given Eddie's backstory. Turns out, Edward was once deeply in love and married to a beautiful Puerto Rican woman named Teresa. One evening at a midtown Manhattan party, Teresa confesses to Edward that she had an affair with his high-class concert manager. Completely unhinged, Edward stomps out of the room. Seeing herself as unclean trash, Teresa jumps out a window.

Thus, we are given yet again another side of Eddie the piano player, the cool guy with his soft-easy smile, when, after the funeral, Edward goes ballistic. Late at night in Hell's Kitchen NYC, he gets himself mugged, robbed and beaten up, enjoying every minute of the violence. He then seeks out more violence again and again and gives as good as he gets, including mauling two policemen.

So violent is Eddie that a strong-arm specialist in the Bowery tells his buddies the next time he fights with the guy he'll need an automatic rifle. The author conveys Eddie's reflections on this period in his life, "Now, looking back on it, he saw the wild man of seven years ago, and thought, What it amounted to, you were crazy, I mean really crazy. Call it horror-crazy."

With this background and insight into Eddie's character, we have a more complete overview of the violence taking place one afternoon at Harriet's Hut. The bar's bouncer, Wally Plyne aka the Harleyville Hugger, admits to taking money for giving Eddie's address to the two hit-men. This causes Lena, the young, attractive waitress and friend of Eddie, to erupt with a torrent of verbal barbs and insults aimed at Plyne. Plyne tells her to shut her mouth but Lena keeps it up.

Plyne explodes, smacking Lena in the face. Lena keeps up the insults. Plyne smacks her again. Lena spits out more insults. More slaps and punches from Plyne. At this point Eddie steps in. Eddie and Plyne exchange punches. Plyne picks up a chair leg to use as a club and then, in response, Eddie grabbing a long, sharp bread knife. Fearing for his life, Plyne races out the back door. Eddie follows, knife in hand. Several minutes later, squeezed in one of the Harleyville Hugger's lethal bear-hugs, Eddie goes for Plyne's arm with the knife but Plyne suddenly shifts position and the knife sinks into Plyne's chest. Plyne slumps over, dead.

I focus on this scene because, to my mind, what happens underscores the author's view of human nature: people are capable of extreme violence; it is only a matter of the flash point. Doesn't matter if a person is an accomplished classical musician or an attractive twenty-seven year old waitress, push the buttons in a certain way and a man or woman will erupt like a volcano. Ah, the horror-crazy buried deep within us all.

David Goodis made it a practice to routinely visit the bars and hangouts and hot spots in Philadelphia's rat-infested, poverty-stricken slums. As a writer and artist, he opened himself to life as it was lived in the urban underbelly of the 1940s and 1950s - desperate, dark and dangerous - and sat at his typewriter and wrote all about it.

5.0

This gritty, hard-boiled novel by David Goodis opens with an action scene where a bloody-faced Turley Linn is running for his life through the alleys of a Philadelphia slum, fleeing from two professional hit-men. Turley ducks into a run-down neighborhood bar called Harriet's Hut and finds his brother Eddie (the novel's main character) who he hasn't seen in over six years. Eddie acknowledges his brother but remains cool and doesn't stop playing his sweet honky-tonk music on the joint's piano. Remaining cool, detached and emotionally uninvolved is the key note (no pun intended) of Eddie's threadbare, solitary life.

In the first few pages we also come to know there is another side to cool Eddie, that is, some years ago Edward Webster Lynn, a concert pianist trained at the Curtis Institute, toured Europe and performed at Carnegie Hall, captivating and mesmerizing audiences with musical talent bordering on genius.

Then why, we may ask, is one of the world's greatest pianists tickling the eighty-eight at a rundown bar? It isn't until midway through the novel that we are given Eddie's backstory. Turns out, Edward was once deeply in love and married to a beautiful Puerto Rican woman named Teresa. One evening at a midtown Manhattan party, Teresa confesses to Edward that she had an affair with his high-class concert manager. Completely unhinged, Edward stomps out of the room. Seeing herself as unclean trash, Teresa jumps out a window.

Thus, we are given yet again another side of Eddie the piano player, the cool guy with his soft-easy smile, when, after the funeral, Edward goes ballistic. Late at night in Hell's Kitchen NYC, he gets himself mugged, robbed and beaten up, enjoying every minute of the violence. He then seeks out more violence again and again and gives as good as he gets, including mauling two policemen.

So violent is Eddie that a strong-arm specialist in the Bowery tells his buddies the next time he fights with the guy he'll need an automatic rifle. The author conveys Eddie's reflections on this period in his life, "Now, looking back on it, he saw the wild man of seven years ago, and thought, What it amounted to, you were crazy, I mean really crazy. Call it horror-crazy."

With this background and insight into Eddie's character, we have a more complete overview of the violence taking place one afternoon at Harriet's Hut. The bar's bouncer, Wally Plyne aka the Harleyville Hugger, admits to taking money for giving Eddie's address to the two hit-men. This causes Lena, the young, attractive waitress and friend of Eddie, to erupt with a torrent of verbal barbs and insults aimed at Plyne. Plyne tells her to shut her mouth but Lena keeps it up.

Plyne explodes, smacking Lena in the face. Lena keeps up the insults. Plyne smacks her again. Lena spits out more insults. More slaps and punches from Plyne. At this point Eddie steps in. Eddie and Plyne exchange punches. Plyne picks up a chair leg to use as a club and then, in response, Eddie grabbing a long, sharp bread knife. Fearing for his life, Plyne races out the back door. Eddie follows, knife in hand. Several minutes later, squeezed in one of the Harleyville Hugger's lethal bear-hugs, Eddie goes for Plyne's arm with the knife but Plyne suddenly shifts position and the knife sinks into Plyne's chest. Plyne slumps over, dead.

I focus on this scene because, to my mind, what happens underscores the author's view of human nature: people are capable of extreme violence; it is only a matter of the flash point. Doesn't matter if a person is an accomplished classical musician or an attractive twenty-seven year old waitress, push the buttons in a certain way and a man or woman will erupt like a volcano. Ah, the horror-crazy buried deep within us all.

David Goodis made it a practice to routinely visit the bars and hangouts and hot spots in Philadelphia's rat-infested, poverty-stricken slums. As a writer and artist, he opened himself to life as it was lived in the urban underbelly of the 1940s and 1950s - desperate, dark and dangerous - and sat at his typewriter and wrote all about it.

With Sincerest Regrets by Russell Edson

A slim collection of delightfully quirky pieces by Russell Edson, an author who jokingly referred to himself as "Little Mr. Prose Poem." Here is the title piece. At the bottom, beneath the Gary Larson cartoon, is one of my own quirky micro-fictions I had published in years past.

WITH SINCEREST REGRETS

Like a monstrous snail, a toilet slides into a living room on a track of wet, demanding to be loved.

It is impossible, and we tender our sincerest regrets. In the book of the heart there is no mention made of plumbing.

And though we have spent our intimacy many times with you, you belong to an unfortunate reference, which we would rather not embrace ...

The toilet slides away ...

THE STIFFS

A cartoonist starts a new comic strip about dead people called The Stiffs. The humor is strictly deadpan, the action dead serious, and the Stiff family a bunch of real stiffs - stiff enough, that is, for all the readers to die laughing.

5.0

A slim collection of delightfully quirky pieces by Russell Edson, an author who jokingly referred to himself as "Little Mr. Prose Poem." Here is the title piece. At the bottom, beneath the Gary Larson cartoon, is one of my own quirky micro-fictions I had published in years past.

WITH SINCEREST REGRETS

Like a monstrous snail, a toilet slides into a living room on a track of wet, demanding to be loved.

It is impossible, and we tender our sincerest regrets. In the book of the heart there is no mention made of plumbing.

And though we have spent our intimacy many times with you, you belong to an unfortunate reference, which we would rather not embrace ...

The toilet slides away ...

THE STIFFS

A cartoonist starts a new comic strip about dead people called The Stiffs. The humor is strictly deadpan, the action dead serious, and the Stiff family a bunch of real stiffs - stiff enough, that is, for all the readers to die laughing.

What a Man Can See by Russell Edson

This collection gathers short pieces of sentence pie where Russell Edson stretched language as if words were made of silly putty, as if words were the silly puddy neck of a silly puddy language goose. Here are two of my favorites from the book. And at the very bottom, below the illustration of a man all dressed up in coat and tie, is one of my own microfictions. Enjoy.

WHAT A MAN CAN SEE

There was a tower where a man said I can live. After grief it can happen that he comes. Then he saw summer its field and its tree. He heard the wind and he saw a cloud.

THE FALL

There was a man who found two leaves and came indoors holding them out saying to his parents that he was a tree.

To which they said then go into the yard and do not grow in the living room as your roots may ruin the carpet.

He said I was fooling I am not a tree and he dropped his leaves.

But his parents said look it is fall.

NO SHILLY-SHALLY

Mr. Snorkle cuts a grapefruit in half and presses each half against his ears. “I want to hear what it sounds like to squeeze a grape.”

“You’re all mixed up, Mr. Snorkel.”

Mr. Snorkle squeeses harder. “I hear it! I hear it! It sounds like wet water.”

“You’re completely and totally mixed up, Mr. Snorkle.”

“I never shilly-shally. My ears hear the sound of wet grape. I squeeze, therefore I am.”

5.0

This collection gathers short pieces of sentence pie where Russell Edson stretched language as if words were made of silly putty, as if words were the silly puddy neck of a silly puddy language goose. Here are two of my favorites from the book. And at the very bottom, below the illustration of a man all dressed up in coat and tie, is one of my own microfictions. Enjoy.

WHAT A MAN CAN SEE

There was a tower where a man said I can live. After grief it can happen that he comes. Then he saw summer its field and its tree. He heard the wind and he saw a cloud.

THE FALL

There was a man who found two leaves and came indoors holding them out saying to his parents that he was a tree.

To which they said then go into the yard and do not grow in the living room as your roots may ruin the carpet.

He said I was fooling I am not a tree and he dropped his leaves.

But his parents said look it is fall.

NO SHILLY-SHALLY

Mr. Snorkle cuts a grapefruit in half and presses each half against his ears. “I want to hear what it sounds like to squeeze a grape.”

“You’re all mixed up, Mr. Snorkel.”

Mr. Snorkle squeeses harder. “I hear it! I hear it! It sounds like wet water.”

“You’re completely and totally mixed up, Mr. Snorkle.”

“I never shilly-shally. My ears hear the sound of wet grape. I squeeze, therefore I am.”

Reginald by Saki

Lesson to last a lifetime - never put pressure on an aesthete or lover of books or someone with highly refined taste to attend a social occasion filled with idle chit-chat. It will not work as the narrator of this delightfully hilarious Saki tale finds out the hard way. And keeping in the spirit of this snapping Saki shorty and as something of a bonus (I hope), I have included my own microfiction beneath the illustration of those two Victorian gentlemen. Bon appétit.

REGINALD

I did it–I who should have known better. I persuaded Reginald to go to the McKillops’ garden-party against his will.

We all make mistakes occasionally.

“They know you’re here, and they’ll think it so funny if you don’t go. And I want particularly to be in with Mrs. McKillop just now.”

“I know, you want one of her smoke Persian kittens as a prospective wife for Wumples–or a husband, is it?” (Reginald has a magnificent scorn for details, other than sartorial.) “And I am expected to undergo social martyrdom to suit the connubial exigencies” –

“Reginald! It’s nothing of the kind, only I’m sure Mrs. McKillop Would be pleased if I brought you. Young men of your brilliant attractions are rather at a premium at her garden-parties.”

“Should be at a premium in heaven,” remarked Reginald complacently.

“There will be very few of you there, if that is what you mean. But seriously, there won’t be any great strain upon your powers of endurance; I promise you that you shan’t have to play croquet, or talk to the Archdeacon’s wife, or do anything that is likely to bring on physical prostration. You can just wear your sweetest clothes and moderately amiable expression, and eat chocolate-creams with the appetite of a blase parrot. Nothing more is demanded of you.”

Reginald shut his eyes. “There will be the exhaustingly up- to-date young women who will ask me if I have seen San Toy: a less progressive grade who will yearn to hear about the Diamond Jubilee–the historic event, not the horse. With a little encouragement, they will inquire if I saw the Allies march into Paris. Why are women so fond of raking up the past? They’re as bad as tailors, who invariably remember what you owe them for a suit long after you’ve ceased to wear it.”

“I’ll order lunch for one o’clock; that will give you two and a half hours to dress in.”

Reginald puckered his brow into a tortured frown, and I knew that my point was gained. He was debating what tie would go with which waistcoat.

Even then I had my misgivings.

* * *

During the drive to the McKillops’ Reginald was possessed with a great peace, which was not wholly to be accounted for by the fact that he had inveigled his feet into shoes a size too small for them. I misgave more than ever, and having once launched Reginald on to the McKillops’ lawn, I established him near a seductive dish of marrons glaces, and as far from the Archdeacon’s wife as possible; as I drifted away to a diplomatic distance I heard with painful distinctness the eldest Mawkby girl asking him if he had seen San Toy.

It must have been ten minutes later, not more, and I had been having QUITE an enjoyable chat with my hostess, and had promised to lend her The Eternal City and my recipe for rabbit mayonnaise, and was just about to offer a kind home for her third Persian kitten, when I perceived, out of the corner of my eye, that Reginald was not where I had left him, and that the marrons glaces were untasted. At the same moment I became aware that old Colonel Mendoza was essaying to tell his classic story of how he introduced golf into India, and that Reginald was in dangerous proximity. There are occasions when Reginald is caviare to the Colonel.

“When I was at Poona in ’76” –

“My dear Colonel,” purred Reginald, “fancy admitting such a thing! Such a give-away for one’s age! I wouldn’t admit being on this planet in ’76.” (Reginald in his wildest lapses into veracity never admits to being more than twenty- two.)

The Colonel went to the colour of a fig that has attained great ripeness, and Reginald, ignoring my efforts to intercept him, glided away to another part of the lawn. I found him a few minutes later happily engaged in teaching the youngest Rampage boy the approved theory of mixing absinthe, within full earshot of his mother. Mrs. Rampage occupies a prominent place in local Temperance movements.

As soon as I had broken up this unpromising tete-a-tete and settled Reginald where he could watch the croquet players losing their tempers, I wandered off to find my hostess and renew the kitten negotiations at the point where they had been interrupted. I did not succeed in running her down at once, and eventually it was Mrs. McKillop who sought me out, and her conversation was not of kittens.

“Your cousin is discussing Zaza with the Archdeacon’s wife; at least, he is discussing, she is ordering her carriage.”

She spoke in the dry, staccato tone of one who repeats a French exercise, and I knew that as far as Millie McKillop was concerned, Wumples was devoted to a lifelong celibacy.

“If you don’t mind,” I said hurriedly, “I think we’d like our carriage ordered too,” and I made a forced march in the direction of the croquet-ground.

I found everyone talking nervously and feverishly of the weather and the war in South Africa, except Reginald, who was reclining in a comfortable chair with the dreamy, far-away look that a volcano might wear just after it had desolated entire villages. The Archdeacon’s wife was buttoning up her gloves with a concentrated deliberation that was fearful to behold. I shall have to treble my subscription to her Cheerful Sunday Evenings Fund before I dare set foot in her house again.

At that particular moment the croquet players finished their game, which had been going on without a symptom of finality during the whole afternoon. Why, I ask, should it have stopped precisely when a counter-attraction was so necessary? Everyone seemed to drift towards the area of disturbance, of which the chairs of the Archdeacon’s wife and Reginald formed the storm-centre. Conversation flagged, and there settled upon the company that expectant hush that precedes the dawn– when your neighbours don’t happen to keep poultry.

“What did the Caspian Sea?” asked Reginald, with appalling suddenness.

There were symptoms of a stampede. The Archdeacon’s wife looked at me. Kipling or someone has described somewhere the look a foundered camel gives when the caravan moves on and leaves it to its fate. The peptonised reproach in the good lady’s eyes brought the passage vividly to my mind.

I played my last card.

“Reginald, it’s getting late, and a sea-mist is coming on.” I knew that the elaborate curl over his right eyebrow was not guaranteed to survive a sea-mist.

“Never, never again, will I take you to a garden-party. Never . . . You behaved abominably . . . What did the Caspian see?”

A shade of genuine regret for misused opportunities passed over Reginald’s face.

“After all,” he said, “I believe an apricot tie would have gone better with the lilac waistcoat.”

THE BACKHANDED COMPLEMENT

All the people gather round and shower me with compliments. Right in the middle of my shower, someone enters our gathering and delivers a backhanded compliment. I feel all the indignity and shock of having been slapped in the face by the back of someone's hand. Not the smooth palm, but the bony backhand. Had the deliverer of this backhanded compliment remained with us, I would confront him with his affront to my dignity. But the backhander is no longer with us. He delivered his backhanded complement and made his exit. The other members share my indignity and shock at such an insult.

"How coarse and vile!" someone exclaims. "To say such a thing and then exit by the back door."

5.0

Lesson to last a lifetime - never put pressure on an aesthete or lover of books or someone with highly refined taste to attend a social occasion filled with idle chit-chat. It will not work as the narrator of this delightfully hilarious Saki tale finds out the hard way. And keeping in the spirit of this snapping Saki shorty and as something of a bonus (I hope), I have included my own microfiction beneath the illustration of those two Victorian gentlemen. Bon appétit.

REGINALD

I did it–I who should have known better. I persuaded Reginald to go to the McKillops’ garden-party against his will.

We all make mistakes occasionally.

“They know you’re here, and they’ll think it so funny if you don’t go. And I want particularly to be in with Mrs. McKillop just now.”

“I know, you want one of her smoke Persian kittens as a prospective wife for Wumples–or a husband, is it?” (Reginald has a magnificent scorn for details, other than sartorial.) “And I am expected to undergo social martyrdom to suit the connubial exigencies” –

“Reginald! It’s nothing of the kind, only I’m sure Mrs. McKillop Would be pleased if I brought you. Young men of your brilliant attractions are rather at a premium at her garden-parties.”

“Should be at a premium in heaven,” remarked Reginald complacently.

“There will be very few of you there, if that is what you mean. But seriously, there won’t be any great strain upon your powers of endurance; I promise you that you shan’t have to play croquet, or talk to the Archdeacon’s wife, or do anything that is likely to bring on physical prostration. You can just wear your sweetest clothes and moderately amiable expression, and eat chocolate-creams with the appetite of a blase parrot. Nothing more is demanded of you.”

Reginald shut his eyes. “There will be the exhaustingly up- to-date young women who will ask me if I have seen San Toy: a less progressive grade who will yearn to hear about the Diamond Jubilee–the historic event, not the horse. With a little encouragement, they will inquire if I saw the Allies march into Paris. Why are women so fond of raking up the past? They’re as bad as tailors, who invariably remember what you owe them for a suit long after you’ve ceased to wear it.”

“I’ll order lunch for one o’clock; that will give you two and a half hours to dress in.”

Reginald puckered his brow into a tortured frown, and I knew that my point was gained. He was debating what tie would go with which waistcoat.

Even then I had my misgivings.

* * *

During the drive to the McKillops’ Reginald was possessed with a great peace, which was not wholly to be accounted for by the fact that he had inveigled his feet into shoes a size too small for them. I misgave more than ever, and having once launched Reginald on to the McKillops’ lawn, I established him near a seductive dish of marrons glaces, and as far from the Archdeacon’s wife as possible; as I drifted away to a diplomatic distance I heard with painful distinctness the eldest Mawkby girl asking him if he had seen San Toy.

It must have been ten minutes later, not more, and I had been having QUITE an enjoyable chat with my hostess, and had promised to lend her The Eternal City and my recipe for rabbit mayonnaise, and was just about to offer a kind home for her third Persian kitten, when I perceived, out of the corner of my eye, that Reginald was not where I had left him, and that the marrons glaces were untasted. At the same moment I became aware that old Colonel Mendoza was essaying to tell his classic story of how he introduced golf into India, and that Reginald was in dangerous proximity. There are occasions when Reginald is caviare to the Colonel.

“When I was at Poona in ’76” –

“My dear Colonel,” purred Reginald, “fancy admitting such a thing! Such a give-away for one’s age! I wouldn’t admit being on this planet in ’76.” (Reginald in his wildest lapses into veracity never admits to being more than twenty- two.)

The Colonel went to the colour of a fig that has attained great ripeness, and Reginald, ignoring my efforts to intercept him, glided away to another part of the lawn. I found him a few minutes later happily engaged in teaching the youngest Rampage boy the approved theory of mixing absinthe, within full earshot of his mother. Mrs. Rampage occupies a prominent place in local Temperance movements.

As soon as I had broken up this unpromising tete-a-tete and settled Reginald where he could watch the croquet players losing their tempers, I wandered off to find my hostess and renew the kitten negotiations at the point where they had been interrupted. I did not succeed in running her down at once, and eventually it was Mrs. McKillop who sought me out, and her conversation was not of kittens.

“Your cousin is discussing Zaza with the Archdeacon’s wife; at least, he is discussing, she is ordering her carriage.”

She spoke in the dry, staccato tone of one who repeats a French exercise, and I knew that as far as Millie McKillop was concerned, Wumples was devoted to a lifelong celibacy.

“If you don’t mind,” I said hurriedly, “I think we’d like our carriage ordered too,” and I made a forced march in the direction of the croquet-ground.

I found everyone talking nervously and feverishly of the weather and the war in South Africa, except Reginald, who was reclining in a comfortable chair with the dreamy, far-away look that a volcano might wear just after it had desolated entire villages. The Archdeacon’s wife was buttoning up her gloves with a concentrated deliberation that was fearful to behold. I shall have to treble my subscription to her Cheerful Sunday Evenings Fund before I dare set foot in her house again.

At that particular moment the croquet players finished their game, which had been going on without a symptom of finality during the whole afternoon. Why, I ask, should it have stopped precisely when a counter-attraction was so necessary? Everyone seemed to drift towards the area of disturbance, of which the chairs of the Archdeacon’s wife and Reginald formed the storm-centre. Conversation flagged, and there settled upon the company that expectant hush that precedes the dawn– when your neighbours don’t happen to keep poultry.

“What did the Caspian Sea?” asked Reginald, with appalling suddenness.

There were symptoms of a stampede. The Archdeacon’s wife looked at me. Kipling or someone has described somewhere the look a foundered camel gives when the caravan moves on and leaves it to its fate. The peptonised reproach in the good lady’s eyes brought the passage vividly to my mind.

I played my last card.

“Reginald, it’s getting late, and a sea-mist is coming on.” I knew that the elaborate curl over his right eyebrow was not guaranteed to survive a sea-mist.

“Never, never again, will I take you to a garden-party. Never . . . You behaved abominably . . . What did the Caspian see?”

A shade of genuine regret for misused opportunities passed over Reginald’s face.

“After all,” he said, “I believe an apricot tie would have gone better with the lilac waistcoat.”

THE BACKHANDED COMPLEMENT

All the people gather round and shower me with compliments. Right in the middle of my shower, someone enters our gathering and delivers a backhanded compliment. I feel all the indignity and shock of having been slapped in the face by the back of someone's hand. Not the smooth palm, but the bony backhand. Had the deliverer of this backhanded compliment remained with us, I would confront him with his affront to my dignity. But the backhander is no longer with us. He delivered his backhanded complement and made his exit. The other members share my indignity and shock at such an insult.

"How coarse and vile!" someone exclaims. "To say such a thing and then exit by the back door."

Het gevaar by Jos Vandeloo

Het gevaar (The Danger) is Jos Vandeloo's bleak, existential novel of three men contaminated by radiation, a tale of warning, especially in the aftermath of Chernobyl and Three Mile Island.

The novel opens with a Prologue wherein the main character, Alfred Benting, travels on a train and encounters a grim, forbidding stranger prompting him to have grim forbidding thoughts about living day-to-day in our modern, urbanized world. Benting reflects how a train of strangers is a microcosm of society - a society populated with unloving, superficial individuals, men and women who, in the end, can only have a questionable friendship with their own shadows.

I cite Benting's reflections to highlight the depth of alienation and dehumanization he experiences in the world at large before he undergoes his specific medical ordeal. And the medical ordeal is the book's alpha and omega.

Exposed to high doses of radiation via a mishap at the nuclear station where he works, Benting is washed, scrubbed, and swabbed and then, along with two other men likewise exposed, confined to a hospital room, placed under strict observation and then subjected to a barrage of medications, vitamins and tests. Sound depressing? Welcome to the world of existential storytelling -- Jos Vanderloo is a master.

Right from the outset Benting realizes he is part of an antiseptic modernized hell. One of the other men, Martin Molenaar, starts vomiting violently. Molenaar's tongue is swollen and takes on a strange color; he has hundreds of small blisters on his hands and face, which is understandable since Molenaar had the greatest level of radioactive exposure.

A doctor and nurse enter the room to record the reaction and general condition of the patients, rub the three men with ointment, and then the doctor measures radiation levels using a counting mechanism and reads off numbers to the nurse. Benting muses on how he and the other two men have absolutely no power to decide their own fate; rather, their lives are now controlled by the medical staff squarely in charge - if, that is, being wretchedly sick and isolated in a small white-walled room can be considered living.

A few days pass and Molenaar is removed from the room since his body is so wasted he stands zero chance of recovering. So, there are now two men, Benting and Dupont, who must deal with vomiting, headaches, diarrhea, skin boils, foul smells of their own skin and sour tastes in their own mouth, not to mention being subjected to continual observation and testing.

At one point a doctor enters and Benting tells the physician with a sense of irony that they are being spoiled by all the attention and medicines. The doctor laughs at Benting remark. Benting broods on how weird the sound of laughter is in such a room room. With a dose of black humor he thinks there should be a sign on on of the walls stating in bold letters:

NO LAUGHING HERE, LAUGHING IS STRICTLY FORBIDDEN. OFFENDERS WILL BE PUNISHED BY FORCED LABOR.

Several days pass and doctor visits become less frequent - Benting and Dupont are left to suffer in solitude. Despite their deteriorating condition and defying all standards of public health, Dupont devises a scheme to escape. Benting listens - he's willing to go along with his roommate's plan.

Will Dupont and Benting really sneak down the hallway, take an elevator to the basement and ride away unseen in a stolen ambulance to at least die on their own terms in the fresh air of the "real" world?

Reading Jos Vanderloo's short novel reminds me of The Wall by Jean Paul Sartre, a story where three political prisoners are locked in a cellar room on a cold evening, condemned to be taken out to a yard the next morning and shot. True, radiation poison isn't exactly the same as standing in front of a firing squad, but, then again, there is something about the certainty of knowing your days can be counted on the fingers of one hand and you are face-to-face with your own death.

Josephus Albertus "Jos" Vandeloo (1925 – 2015), Belgian novelist and poet.

5.0

Het gevaar (The Danger) is Jos Vandeloo's bleak, existential novel of three men contaminated by radiation, a tale of warning, especially in the aftermath of Chernobyl and Three Mile Island.

The novel opens with a Prologue wherein the main character, Alfred Benting, travels on a train and encounters a grim, forbidding stranger prompting him to have grim forbidding thoughts about living day-to-day in our modern, urbanized world. Benting reflects how a train of strangers is a microcosm of society - a society populated with unloving, superficial individuals, men and women who, in the end, can only have a questionable friendship with their own shadows.

I cite Benting's reflections to highlight the depth of alienation and dehumanization he experiences in the world at large before he undergoes his specific medical ordeal. And the medical ordeal is the book's alpha and omega.

Exposed to high doses of radiation via a mishap at the nuclear station where he works, Benting is washed, scrubbed, and swabbed and then, along with two other men likewise exposed, confined to a hospital room, placed under strict observation and then subjected to a barrage of medications, vitamins and tests. Sound depressing? Welcome to the world of existential storytelling -- Jos Vanderloo is a master.

Right from the outset Benting realizes he is part of an antiseptic modernized hell. One of the other men, Martin Molenaar, starts vomiting violently. Molenaar's tongue is swollen and takes on a strange color; he has hundreds of small blisters on his hands and face, which is understandable since Molenaar had the greatest level of radioactive exposure.

A doctor and nurse enter the room to record the reaction and general condition of the patients, rub the three men with ointment, and then the doctor measures radiation levels using a counting mechanism and reads off numbers to the nurse. Benting muses on how he and the other two men have absolutely no power to decide their own fate; rather, their lives are now controlled by the medical staff squarely in charge - if, that is, being wretchedly sick and isolated in a small white-walled room can be considered living.

A few days pass and Molenaar is removed from the room since his body is so wasted he stands zero chance of recovering. So, there are now two men, Benting and Dupont, who must deal with vomiting, headaches, diarrhea, skin boils, foul smells of their own skin and sour tastes in their own mouth, not to mention being subjected to continual observation and testing.

At one point a doctor enters and Benting tells the physician with a sense of irony that they are being spoiled by all the attention and medicines. The doctor laughs at Benting remark. Benting broods on how weird the sound of laughter is in such a room room. With a dose of black humor he thinks there should be a sign on on of the walls stating in bold letters:

NO LAUGHING HERE, LAUGHING IS STRICTLY FORBIDDEN. OFFENDERS WILL BE PUNISHED BY FORCED LABOR.

Several days pass and doctor visits become less frequent - Benting and Dupont are left to suffer in solitude. Despite their deteriorating condition and defying all standards of public health, Dupont devises a scheme to escape. Benting listens - he's willing to go along with his roommate's plan.

Will Dupont and Benting really sneak down the hallway, take an elevator to the basement and ride away unseen in a stolen ambulance to at least die on their own terms in the fresh air of the "real" world?

Reading Jos Vanderloo's short novel reminds me of The Wall by Jean Paul Sartre, a story where three political prisoners are locked in a cellar room on a cold evening, condemned to be taken out to a yard the next morning and shot. True, radiation poison isn't exactly the same as standing in front of a firing squad, but, then again, there is something about the certainty of knowing your days can be counted on the fingers of one hand and you are face-to-face with your own death.

Josephus Albertus "Jos" Vandeloo (1925 – 2015), Belgian novelist and poet.

Exley by Brock Clarke

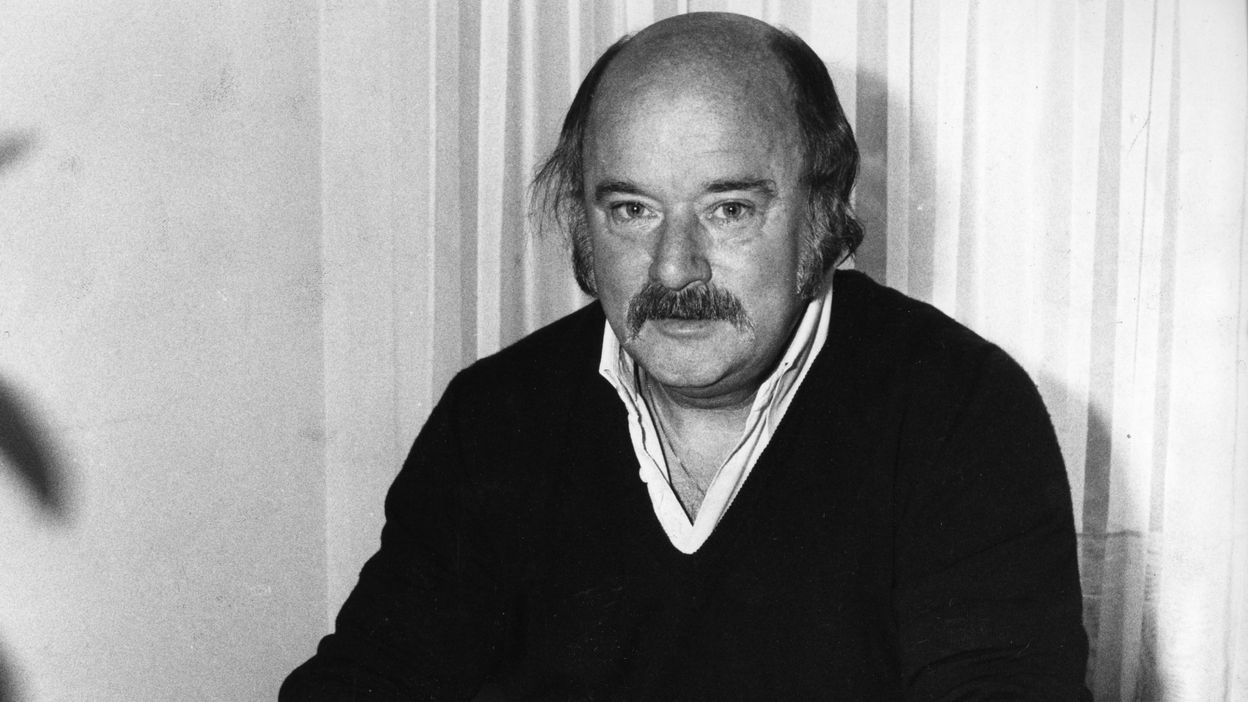

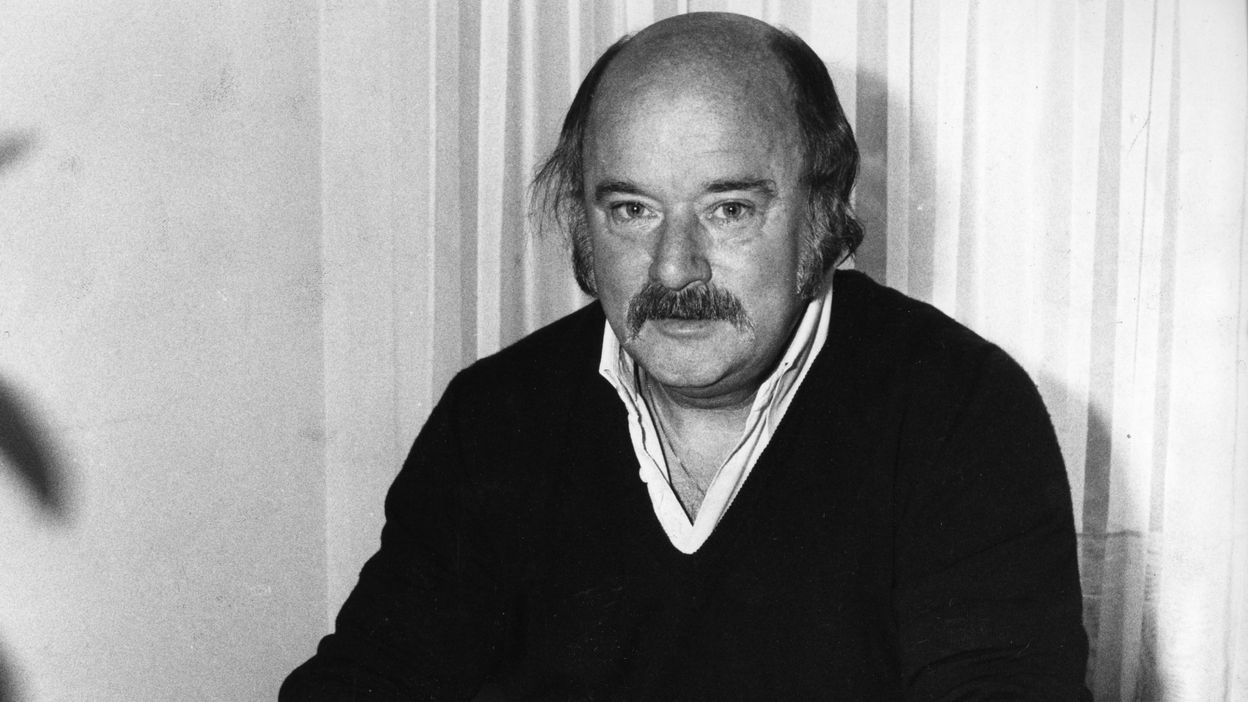

Exley, the novel's title - as in American writer Frederick Exley (pictured above), author of his notorious 1968 fictionalized autobiography, A Fan’s Notes

Contemporary American author Brock Clarke’s moving story of a son’s love for his missing dad. The novel takes place in Watertown, New York at the time of George W. Bush's war in Iraq,

The book features two alternating first-person narrators: a nine-year old boy by the name of Miller and Miller’s therapist, a doctor who, during the course of his dealings with Miller, receives initiation into the literary world of A Fan’s Notes. By my reckoning, the novel’s switching back and forth between narrators, young patient and seasoned therapist, is the perfect choice for all of the tale's surprising twists and turns.

Take my word for it here, Clarke’s novel packs a real emotional charge. As readers, we want to keep turning the pages to learn what happens next, to discover what is fact and what is fiction since Miller and his therapist have their big hearts in the right place but their respective stories are as unreliable as can be.

Every stage of the unfolding drama reveals surprises so I will not disclose any details that could act as spoilers; rather, here is a thumbnail of each of the three, no, let’s make that four, main characters:

Miller Le Ray - Since Miller at age nine is a precocious reader of books, he is moved up from third grade to seventh grade with a class of thirteen-year olds. He loves his dad so much and since his dad loves Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes, owning many copies, reading and rereading it to the point where he can and does quote freely and allude to continually, Miller does the same. For example, Miller will say or write the first initial of someone’s name, say “K” or “H” similar to what Exley does in his book and, by extension, similar to his dad. Miller lives with his mom and develops a tight emotional connection with his therapist.

Miller’s Mom – Drop dead gorgeous with dark eyes and jet black hair. She is a dedicated professional, the head lawyer in her office where she handles cases of spousal abuse among military personnel. She has plenty of work since Watertown is a big military town. Miller’s mom loves Miller and judges her son in need of some psychotherapy to help him in dealing with his missing father. Thus, she arranges for Miller to see a therapist.

Miller’s Therapist – An experienced and educated psychologist and counselor who continually refers to himself as a health care professional, which has a tincture of irony since a number of his actions are very unprofessional. He also is a thirty-something bachelor who falls deeply in love at first sight with Miller’s mom. The lion’s share of his narrative is a reciting of his Doctor’s Notes, which, as it turns out, isn’t that far removed from Exley’s A Fan’s Notes.

Frederick Exley and his autobiographical novel – The book and the long dead author have a tangible presence on every page; it’s as if there is an Exleyesque film coating thoughts, words and actions. Brock Clarke’s novel will most certainly resonate with an added vibe for readers familiar with Exley’s book.

Incidentally, I intentionally did not give the names of either Miller’s mother or Miller’s therapist since Miller himself employs names as Exleyesque signifiers and also as modes of potential transformation. Does it sound to you like Miller is a bright, perceptive lad? Quite right, which adds a real zest to Clarke's engaging novel.

American author Brock Clarke, born 1968

“There's nothing as quiet as that moment before one person is about to tell another something neither of them wants to hear.”

― Brock Clarke, Exley

5.0

Exley, the novel's title - as in American writer Frederick Exley (pictured above), author of his notorious 1968 fictionalized autobiography, A Fan’s Notes

Contemporary American author Brock Clarke’s moving story of a son’s love for his missing dad. The novel takes place in Watertown, New York at the time of George W. Bush's war in Iraq,

The book features two alternating first-person narrators: a nine-year old boy by the name of Miller and Miller’s therapist, a doctor who, during the course of his dealings with Miller, receives initiation into the literary world of A Fan’s Notes. By my reckoning, the novel’s switching back and forth between narrators, young patient and seasoned therapist, is the perfect choice for all of the tale's surprising twists and turns.

Take my word for it here, Clarke’s novel packs a real emotional charge. As readers, we want to keep turning the pages to learn what happens next, to discover what is fact and what is fiction since Miller and his therapist have their big hearts in the right place but their respective stories are as unreliable as can be.

Every stage of the unfolding drama reveals surprises so I will not disclose any details that could act as spoilers; rather, here is a thumbnail of each of the three, no, let’s make that four, main characters:

Miller Le Ray - Since Miller at age nine is a precocious reader of books, he is moved up from third grade to seventh grade with a class of thirteen-year olds. He loves his dad so much and since his dad loves Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes, owning many copies, reading and rereading it to the point where he can and does quote freely and allude to continually, Miller does the same. For example, Miller will say or write the first initial of someone’s name, say “K” or “H” similar to what Exley does in his book and, by extension, similar to his dad. Miller lives with his mom and develops a tight emotional connection with his therapist.

Miller’s Mom – Drop dead gorgeous with dark eyes and jet black hair. She is a dedicated professional, the head lawyer in her office where she handles cases of spousal abuse among military personnel. She has plenty of work since Watertown is a big military town. Miller’s mom loves Miller and judges her son in need of some psychotherapy to help him in dealing with his missing father. Thus, she arranges for Miller to see a therapist.

Miller’s Therapist – An experienced and educated psychologist and counselor who continually refers to himself as a health care professional, which has a tincture of irony since a number of his actions are very unprofessional. He also is a thirty-something bachelor who falls deeply in love at first sight with Miller’s mom. The lion’s share of his narrative is a reciting of his Doctor’s Notes, which, as it turns out, isn’t that far removed from Exley’s A Fan’s Notes.

Frederick Exley and his autobiographical novel – The book and the long dead author have a tangible presence on every page; it’s as if there is an Exleyesque film coating thoughts, words and actions. Brock Clarke’s novel will most certainly resonate with an added vibe for readers familiar with Exley’s book.

Incidentally, I intentionally did not give the names of either Miller’s mother or Miller’s therapist since Miller himself employs names as Exleyesque signifiers and also as modes of potential transformation. Does it sound to you like Miller is a bright, perceptive lad? Quite right, which adds a real zest to Clarke's engaging novel.

American author Brock Clarke, born 1968

“There's nothing as quiet as that moment before one person is about to tell another something neither of them wants to hear.”

― Brock Clarke, Exley

Vidas imaginárias by Marcel Schwob

Always fascinating and frequently macabre and chilling - we pull back the curtain and enter the world of French symbolist and decadent author Marcel Schwob (1867-1905).

In his Imaginary Lives we encounter twenty-two portraits that are part fact, part myth, part author’s poetic fancy, where the individuals portrayed are taken from such fields as ancient history, philosophy, art, literature and even the worlds of crime and geomancy, such personages as Septima the enchantress, Petronius the romancer, Fra Dolcino the heretic, Pocahontas the princess, William Phips the treasure hunter and Captain Kidd the pirate. Here are some quotes and my comments on three lives from the collection:

Cyril Tourneur the tragic poet: “Cyril Tourneur was born out of the union of an unknown god with a prostitute. Proof enough of his divine origin has been found in the heroic atheism to which he succumbed. From his mother he inherited the instinct for revolt and luxury, the fear of death, the thrill of passion and the hate of kings. His father bequeathed him his desire for a crown, his pride of power and his joy of creating. To him both parents handed down their taste for nocturnal things, for a red glare in the night, and for blood.” So we read in Marcel Schwob’s first lines supercharged with mythos.

On a slightly more mundane level, Cyril Tourneur was an English dramatist born in 1575, author most notably of The Atheist’s Tragedy, a play of revenge employing rich macabre imagery. But who wants to be constricted within the confines of so called historical facts? Certainly not a fin de siècle symbolist and decadent like Marcel Schwob.