Scan barcode

A review by glenncolerussell

The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies by Clark Ashton Smith

5.0

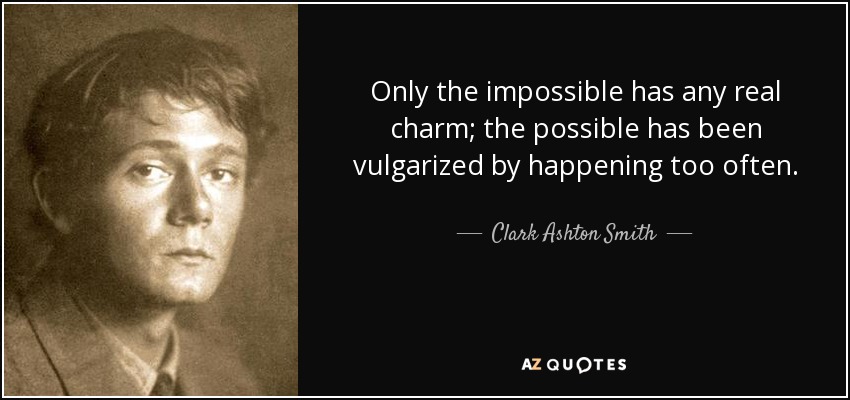

Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961) is surely one of America’s most intriguing and unique authors, a poet and writer of tales of horror, fantasy and science fiction. Born in a small town in Northern California and living nearly all his life in the log cabin build by his parents, Smith didn’t attend school beyond the eighth grade due to psychological problems; rather, all of his learning occurred at home – he read voraciously and committed much to memory, including an encyclopedia and a dictionary cover to cover; he taught himself French and Spanish; he devoured book after book, such classics as Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver's Travels and the works of Edgar Allan Poe. As an adult, along with H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, Smith was a prime contributor to the pulp fiction magazine Weird Tales, and, like Lovecraft, whom he befriended and carried on a live-long correspondence, Smith used his own nightmares as raw material for his fiction.

This fine Penguin edition is a treasure, including many short stories, prose poems and poems along with an informative Introduction by literary scholar, S. T. Joshi. As a way of sharing a taste of what a reader will discover in these pages, I have focused on one short story from the collection, Ubbo-Sathla, noting a number of themes from the tale, themes that recur in much of the author’s work. Also included is my write-up (copied from one of my other reviews) on yet another tale from this Penguin collection: Mother of Toads.

UBBO-SATHLA

“For Ubbo-Sathla is the source and the end. Before the coming of Zhothaqquah or Yok-Zothoth or Kthulhut from the stars, Ubbo-Sathla dwelt in the steaming fens of the newmade Earth.”

So begins this beguiling tale of metaphysical investigation told in arcane language by Clark Ashton Smith, an author for whom fiction was as a way to explore the big philosophical questions: Where do we come from? What is the foundation of life? Why are we here? Where are we going?

Again, these questions are asked in the most inscrutable language, for as the author himself explains: "My own conscious ideal has been to delude the reader into accepting an impossibility, or series of impossibilities, by means of a sort of verbal black magic, in the achievement of which I make use of prose-rhythm, metaphor, simile, tone-color, counter-point, and other stylistic resources, like a sort of incantation.”

Similar to young men entering antique shops filled with curios from around the globe (Honoré de Balzac’s The Magic Skin and Théophile Gautier's The Mummy’s Foot come immediately to mind), the tale's protagonist, Paul Tregardis, enters an antique shop and his eye is drawn to something in particular: “the milky crystal in a litter of oddments from many lands and eras.”

And, oh, how that magically enchanted, arcane object quickly becomes the nucleus of occult unfoldings. "Tregardis thinks of his own explorations in hidden lore: he recalled The Book of Eibon, that strangest and rarest of occult forgotten volumes, which is said to have come down through a series of manifold translations from a prehistoric original written in the lost language of Hyperborea."

After leaving the shop, crystal in hand, little does Tregardis know he now holds an enchanted object that will bring the book of his very own memories to life.

As per vintage Clark Ashton Smith, that aforementioned remote, secret book, The Book of Eibon, was purported to have been the handiwork of a great wizard in touch with the heart of the heart of all power within the universe. "This wizard, who was mighty among sorcerers, had found a cloudy stone, orb-like and somewhat flattened at the ends, in which he could behold many visions of the terrene past, even to the Earth's beginning, when Ubbo-Sathla, the unbegotten source, lay vast and swollen and yeasty amid the vaporing slime. . . But of that which he beheld, Zon Mezzamalech left little record; and people say that he vanished presently, in a way that is not known; and after him the cloudy crystal was lost."

With a wizard and sorcery added to the equation, our narrator is in for unexpected twists to his adventures.

The more our young narrator peers into his newly purchased crystal, the more all of the normal boundaries of time and space expand and take on strange forms. “As if he looked upon an actual world, cities, forests, mountains, seas and meadows flowed beneath him, lightening and darkening as with the passage of days and nights in some weirdly accelerated stream of time.”

Is he in twentieth century London or some other past and future time? Or, as unfathomable as it might seem, two or even all three together? It is hard for poor Paul Tregardis to tell. In this and in many other Clark Ashton Smith tales, it is left to us as readers to fathom our own conclusions, as nebulous as they might be.

Paul feels something very strange, as if he is under the influence of hashish. The walls begin to wobble as if they are made of smoke; all the men and women in the streets begin to appear as so many ghosts and shades; the whole scene takes on the cast of a vast phantasm.

Is Paul dreaming or hallucinating? Could be. But many the time in a Clark Ashton Smith tale, a dream or vision quickly slides into an unending nightmare. Recall the author mined his own nightmares during protracted illnesses to fuel his fantasies and tales of horror.

In such a nightmare, what other evil or unforeseen event can happen? Answer: for Clark Ashton Smith, a character’s very identity can shift and change not only once but multiple times. “He seemed to live unnumbered lives, to die myriad deaths, forgetting each time the death and life that had gone before. He fought as a warrior in half-legendary battles; he was a child playing in the ruins of some olden city of Mhu Thulan; he was the king who had reigned when the city was in its prime, the prophet who had foretold its building and its doom. He became a barbarian of some troglodytic tribe, fleeing from the slow, turreted ice of a former glacial age into lands illumed by the ruddy flare of perpetual volcanoes. Then, after incomputable years, he was no longer man, but a man-like beast, roving in forests of giant fern and calamite, or building an uncouth nest in the boughs of mighty cycads."

Clark Ashton Smith, such an imagination, such psychedelic, phantasmagorical visions - not only can a man or woman, plant or beast change, the entire universe can compress itself into a grey, formless mass of slime with the name Ubbo-Sathla.

MOTHER OF TOADS

This tale begins with Pierre, young apprentice of the village apothecary, making one of his journeys to the secluded hut of Mère Antoinette, a big ugly witch, for the purpose of returning with a mysterious brew for his master’s secret concoction. After giving Pierre what he came for, the witch beckons the lad to stay. We read his response: “Pierre tossed his head with the disdain of a young Adonis. The witch was more than twice his age, and her charms were too uncouth and unsavory to tempt him for an instant. She was repellently fat and lumpish, and her skin possessed an unwholesome pallor.”

Let’s pause here and ask why do witches appear in so many Western fairy-tales? Robert Bly speaks of the tyranny of patriarchal monotheistic culture, where what is good and pure and divine is male and what comes from nature is negative, chaotic and destructive. And since women are so closely aligned with nature and fertility, their female nature is denied a place in the spiritual realm or godhead, however their energy and power does not go away; rather, it goes underground and later emerges as the witch.

Since village rumors abound regarding the witch’s wickedness and her many toad-servants doing her evil bidding, we can also ask why the master sends young Pierre alone and unprotected to the witch’s hut in the first place. We read: “The old apothecary, whose humor was rough and ribald, had sometimes rallied Pierre concerning Mère Antoinette's preference for him. Remembering certain admonitory gibes, more witty than decent, the boy flushed angrily as he turned to go.” Does the older man have the best interests of the young man at heart? Robert Bly alludes to how the older generation of men in being too naïve themselves have betrayed younger men, causing those younger men to be, in turn, too naïve and gullible.

So, after Pierre refuses her offer to stay, the witch proposes he drink a cup of her fine red wine. Pierre smells the odors of hot, delicious spices and tells the witch he will drink if the wine contains none of her concoctions. Of course, the witch assures him its sound, good wine that will warm his stomach. Did I mentioned naïve and gullible? Pierre drinks the wine. Big mistake. All of Pierre’s sense are radically transformed and distorted – the big, fat witch starts looking pretty good, after all. Do I hear echoes of how drinking can alter and dull our perceptions? Anyway, the deed is done – the witch gets to have a handsome, young lover for the night.

Pierre wakes up sober, sees what has happened and runs away. But the evil witch possesses strange powers. Thousands of her toad-servants block his path and force him to return to the hut. The witch again proposes Pierre stay with her and drink of the wine. At this point, here is the exchange:

"I will not drink your wine," he said firmly. "You are a foul witch, and I loathe you. Let me go."

"Why do you loathe me?" croaked Mère Antoinette. "I can give you all that other women give ... and more."

"You are not a woman," said Pierre. "You are a big toad. I saw you in your true shape this morning. I'd rather drown in the marsh-waters than stay with you again."

Sorry, Pierre, it doesn’t sound like you are using your wits – when confronting powerful evil, you don’t win any points by being honest. Even as children Hansel and Gretel knew what is needed in dealing with a wicked witch is not honesty but cleverness. How does this tale end? You will have to pick up this outstanding collection and read for yourself.

Here are a number of cover illustrations of tales from this Clark Ashton Smith collection: